In December, a team of authors proposed a new panel to mobilise ocean science and bridge the science-policy interface—dubbed the International Panel for Ocean Sustainability (IPOS). Drawing inspiration from existing institutions like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), but going beyond the limits of current initiatives, their vision could help to deliver the goals of the UN Decade of Ocean Science (2021-2030), drawing ocean science together under a common global framework to achieve Sustainable Development Goal 14, Life Below Water. For this month’s feature, Back to Blue interviews the new initiative’s lead co-author, Tanya Brodie Rudolph, from the Centre for Sustainability Transitions at the University of Stellenbosch.

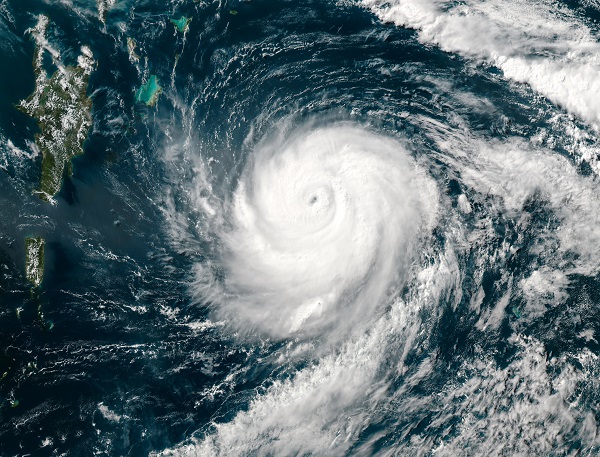

While climate change conferences date back decades, the ocean has only recently become a substantive part of negotiations and part of the climate agenda more broadly. There is growing awareness about the ocean’s fundamental role in regulating planetary health and mitigating climate change, and an appreciation that our ocean is approaching the physical, chemical and ecological tipping points that will trigger the collapse of the key climate and life support roles that it provides. There is, in short, no way to achieve the Paris agreements’ targets without protecting our ocean.

Yet despite the importance of the ocean to tackling climate change, the body of scientific knowledge about this ecosystem is fragmented in research silos. It can be exclusionary and remote, clustered in universities with little-to-no contact to the communities who directly live with and experience the changes the ocean is undergoing. And it is not influencing policy decision-making as directly as the science community would like.

The outputs of ocean science institutions and researchers are valuable but each have restrictions that limit their usefulness in informing decision-making. “There are many bodies and institutions that deal with the ocean, but it is hard to find coherent methodologies and governance arrangements,” says Ms Brodie Rudolph. “There is a coalescence needed to bring ocean knowledge together and make it actionable.”

Ms Brodie Rudolph, together with Francoise Gaill, an adviser at the National Center for Scientific Research in France, recently published the proposal to form IPOS, which would serve as a co-ordinating mechanism to integrate knowledge systems and bridge the ocean science and policy divide.

The ocean science jigsaw

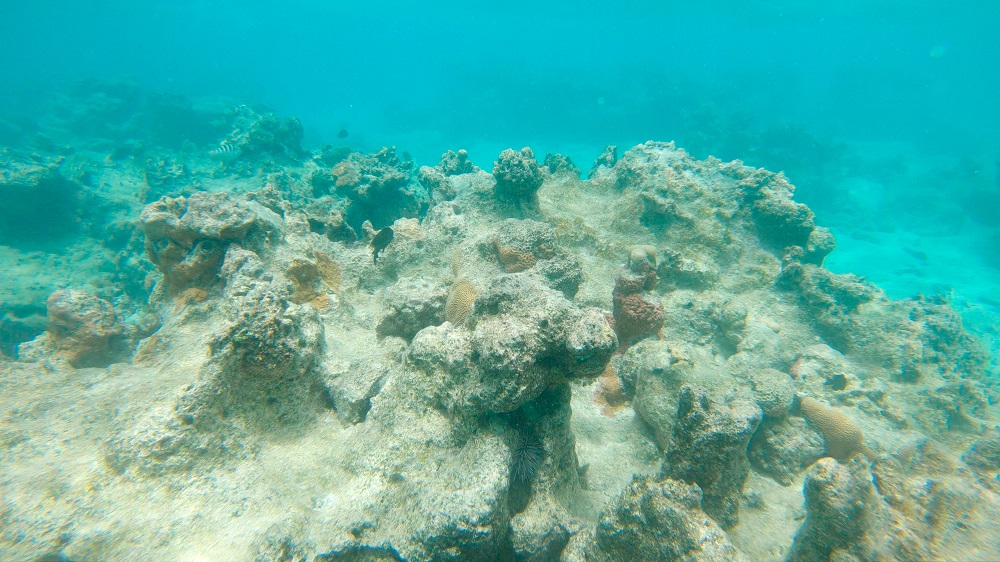

One challenge facing ocean science is the silos arising from research fragmented across a complex ecosystem. A second is the narrow science base that often lacks input from key communities that have differing forms of knowledge to share, such as small-scale fisheries, indigenous people, and local communities who are experienced stewards of coastal and ocean spaces.

“Ocean science is developed in institutions focused on specific aspects of knowledge, but it is not representative of all knowledge of that topic,” says Ms Brodie Rudolph. “If we look at a local community’s experience in traditional fishing grounds, they have been fishing for a thousand, maybe 10,000 years. They have an insight about the change that is happening in local species, in the ocean spaces they have always fished in. That knowledge has not formed part of these [scientific] ocean reports because it is quite qualitative, which can impact scientific rigour and credibility. But for legitimate evidence-based decisions, we need a broader approach to knowledge and networks of knowledge.”

The proposed IPOS recognises the work already happening to progress ocean science while confronting the limitations of different institutions’ mandates and perspectives. There are valuable assessments that cover aspects of the ocean system, such as the IPCC, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), and the World Ocean Assessment. The goal of IPOS is partly to be a mechanism to mobilise and synthesise existing and emerging knowledge and partly to identify and close remaining gaps

Ocean assessments, for instance, provide detailed scientific analyses of different aspects of marine life, and such studies date back over a century, but “there is no cohesive concentration of knowledge that is synthesised in a way that is useful, actionable and implementable at a local level,” says Ms Brodie Rudolph. The World Ocean Assessment is an impressive, detailed record of the state of ocean health but it lacks forward-looking scenarios that, according to Ms Brodie Rudolph, are an important stimulus for policy decision-making.

The IPCC includes ocean assessment and recognises the ocean’s role in regulating the climate as a carbon sink, but the focus of these reports is climate. The IPBES, meanwhile, offers useful scenarios and forward-looking analysis, Ms Brodie Rudolph says, but approaches the ocean from a biome perspective. This simply mean an area that is classified according to the species that live in it. “The ocean is part of the earth system. It is an integral part of the air we breathe, the food we eat, and the weather we experience, so a biome perspective is limiting.” The International Resources Panel published a report on coastal resources, which looks at coastal and land governance and the overlap that occurs on the coast in areas where land and ocean uses intersect, but governance of combined impacts is approached through separate laws.

“Those two need to be integrated to have an idea of the impacts we are having,” says Ms Brodie Rudolph. She adds that an issue like eutrophication, characterised by excessive plant and algal growth due to increased availability of inputs like carbon dioxide or nutrient fertiliser, is governed by specific instruments, but there are multiple impact pathways such as eutrophication from farming, tourism development, overfishing and agriculture farms. “Each of those parts are governed by different instruments. We need to understand how these things intersect.”

The IPOS work begins

IPOS is currently in its germinal phase as its participants and experts map out the design, role and mandate that such an institution would play. According to Ms Brodie Rudolph, scenarios and modelling will be a critical part of its work, as these are useful in guiding decision-makers and are important elements of the IPCC’s influential work. Inclusion will be another priority, with a dedicated taskforce set up. “The IPOS needs to be legitimate and reflect the voice of all people,” remarks Ms Brodie Rudolph.

She explains that IPOS could help to make ocean science more accessible. Few people can wade through the lengthy reports produced by scientific researchers. The team is exploring how different media and formats, like tutorials, podcasts, short videos and the arts, can help improve ocean science communication.

IPOS will also focus on ways to “translate global generic recommendations that often come out of [scientific] reports, and making them more applicable and actionable at a local scale,” says Ms Brodie Rudolph. “One of the lessons that we can learn from IPBES has been the methodology of stakeholder engagement at a local scale, and capacity building during knowledge production. Since every region and locality in the world will require a nuanced response that is particular to its context, it will be important for IPOS to establish the process through which this local resolution of general principles and recommendations for ocean use, management and governance can authentically and legitimately be established.”

There are still gaps in ocean science, Ms Brodie Rudolph says. Over 90% of ocean species are not described, for example. To start tackling this gap, Back to Blue is leading research in critical areas like the scale and impact of chemical pollution and acidification, and tracking plastics management policies through benchmarking analyses.

But with so much science already existing but underutilised, IPOS could serve a planetary good in co-ordinating and synthesising the vast quantities of data and research that already exist but are poorly integrated. IPOS will, Ms Brodie Rudolph says, “co-ordinate all the incredible knowledge we already have in a way that is more practical, useful and engaging and that everyone can engage with and understand, from policymakers to citizens.” That could ensure that ocean knowledge informs decision-making that supports a healthy, vibrant and productive ocean for current and future generations.

THE SUSTAINABILITY PROJECT

WORLD OCEAN INITIATIVE

WE LOVE TO HEAR FROM YOU

We welcome your feedback and comments.

If you have an editorial or media related request, a member of the media team will get back to you.

EXPLORE MORE CONTENT ABOUT THE OCEAN

THANK YOU

Thank you for your interest in Back to Blue, please feel free to explore our content.

CONTACT THE BACK TO BLUE TEAM

If you would like to co-design the Back to Blue roadmap or have feedback on content, events, editorial or media-related feedback, please fill out the form below. Thank you.