The UN Treaty on Plastic Pollution, which is currently being negotiated, must take a fresh look at the risks associated with the plastics industry. Finding creative financial solutions that balance both risk and impact will also be critical.

Key points:

- An estimated US$1.2trn is required to fund the transition to and finance the infrastructure needed for a new plastics economy

- Plastic pollution is a material risk to businesses and investors. The investment community will have to determine when the risks of business-as-usual outweigh the relative risks of building a new circular plastics industry

- In the meantime, financial tools such as blended finance can share risks while deploying capital where it is most needed

- Data standardisation and verifiability, from corporate environmental, social and governance (ESG) metrics to company performance, will be key to building a robust pipeline of projects and attracting more investors

Negotiations to develop a global plastics treaty are under way, and there is pressure to deliver an international instrument that can tackle the current plastic crisis, lay the foundations for a new plastics economy and unlock the financing needed to support the transition to a circular economy.

Governments play a pivotal role in creating the right incentives and regulatory environment to spur change and encourage financiers to step in. And they seem to be ready to act. Many development banks, philanthropists and impact investors already consider plastic and waste management an opportunity rather than a challenge.

But more is needed to attract institutional investors and asset managers to meet the estimated US$1.2trn required to build the necessary infrastructure for a new plastics economy. How can more private sector capital be incentivised to flow into the secondary plastics commodity market? What is holding investors back? And what does it mean for the plastics treaty currently being negotiated?

Plastics: a material risk

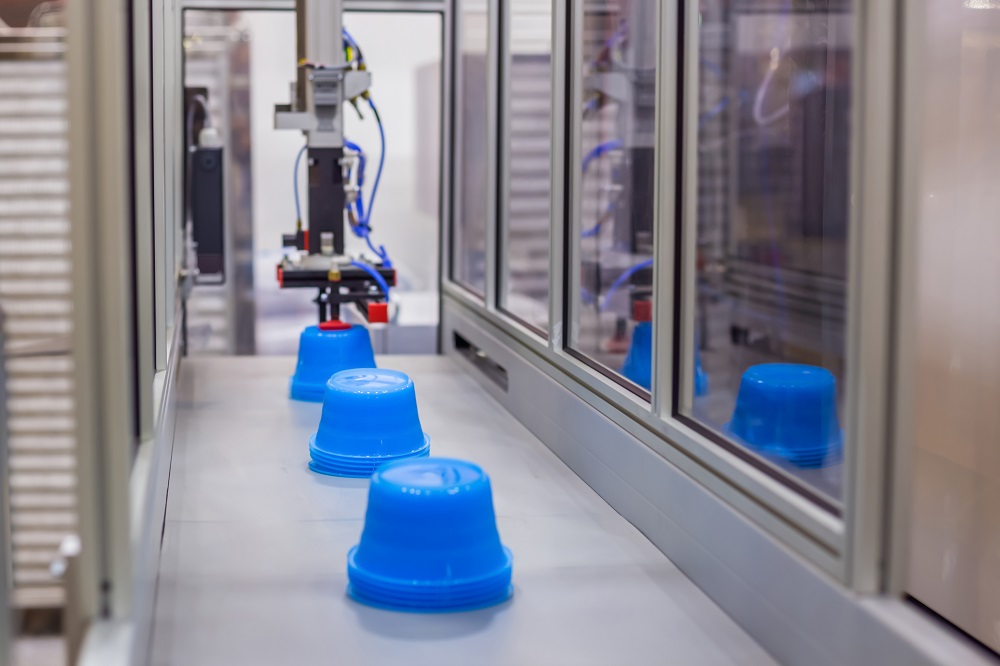

From developing and manufacturing alternative materials down to enhancing collection, sorting and recycling facilities, the entire circular plastics value chain requires technical capacity and investment. This presents financiers with a fleet of opportunities to support and invest in the pathway to a circular plastics industry.

As regulations increasingly push companies to disclose their ESG footprint, and more information about their plastic management becomes available, investors have a chance to better assess the risks associated with the plastics industry and make more informed decisions about where long-term opportunities lie.

Plastic pollution is also quickly becoming a material risk that investors and companies must navigate as they seek to invest in a changing plastics industry. More scrutiny from consumers and regulators poses a reputational and regulatory risk for companies maintaining a business-as-usual stance. As more players commit to a circular plastics economy, businesses that adapt and evolve alongside new regulations will likely maintain a competitive edge.

A growing body of scientific evidence is rapidly changing our understanding of the harmful impacts of plastics, including additives and microplastics, on human and environmental health. And, as awareness grows and scientific literature proliferates, such impacts could be traced back to manufacturers, who will likely become increasingly exposed to litigation risk.

In January 2022, Keurig Canada was fined over its claims on the recyclability of its disposable coffee pods and France’s Danone now faces fresh allegations for failing to account for its plastic use along its production lines. In the US alone plastics-related litigation could exceed US$20bn between 2022 and 2030. Companies should expect to be asked whether they are doing enough to eliminate plastic pollution.

Government bans, taxes and production guidelines on plastic production, use and disposal also create an increased demand for disruptive technologies and alternative and recycled materials. Over time, as supply chain dynamics change and virgin plastic demand diminishes, manufacturers and investors may have to grapple with the transition risk of stranded assets and the liability linked to plastic production.

Growing pains

At the same time, the secondary commodities market is not risk-free and is experiencing growing pains that are symptomatic of a transition. Many emerging markets, where most of the capital is needed, are still perceived as risky and volatile.

Despite good intentions, companies that have committed to increasing the recycled content of their packaging face a shortage of high-quality recycled plastic to meet their pledges. “Reliable supply and high volumes of stable quality feedstock are needed to justify investment in high-quality recycling capacity to meet this demand”, says Jacob Rognhaug, vice president for public affairs system design at Tomra. “By implementing mixed waste sorting before incinerators and landfills, the right feedstock could be provided,” he says.

The lack of high-quality recycled plastic can lead to further problems down the line, especially if companies either turn to lower-content projects or mix cheaper virgin plastics into their product content. Misleading information and cases of greenwashing risk undermining the credibility of, and investor trust in, the recycled plastics market and could set back any progress made on deploying recycled materials.

In many developing countries, informal waste collection for recycling is a common way for people to earn a living. Waste management is also intrinsically linked to how communities are organised, connected and manage their own logistics, jobs and entrepreneurial activities. The sector is, therefore, multidimensional and touches upon intractable issues such as poverty, health, stigma and gender dynamics. This complexity, compounded by a lack of transparency and data, makes any related projects far less attractive to traditional investors.

“Many of the solutions we do have are designed for urban settings,” says Yonathan Shiran, partner and plastics lead at Systemiq. “In rural areas, where dwellings are more scattered, the cost to build out the infrastructure that is needed to collect and process waste is much higher per ton. It is also where there is a higher risk of leakage and where the budget is lowest.”

Finance at work: more fish in the sea?

Shifts in current market dynamics suggest that as business-as-usual risks increase, the relative risks of investing in circular business models decrease. Until that inflection point is reached, however, creative financial tools that are better suited to the vagaries of a transitional period can help hedge the risks.

Blended finance, in particular, provides an important bridge between today’s plastics industry and a fully operational investment market that serves the circular economy. It can channel capital towards high-impact infrastructure projects such as renewable energy or clean water and sanitation. An estimated US$171bn in blended finance has already been deployed towards sustainable initiatives in low- to middle-income countries to-date. Projects that support a circular plastics economy but don’t yet have a commercial track record could potentially qualify and tap into this pool of capital.

“Financial institutions still tend to perceive the second-hand commodities market as too risky, so blended finance is critical to direct capital in this space”, says Ellen Martin, chief impact officer at Circulate Capital. “It’s a valuable tool to share risk and channel capital into market-building initiatives.”

There has also been a sharp increase in debt and equity instruments to support circular business models and companies remediating plastic waste. These financial instruments, many of which are described in Chatham House’s report, Financing an inclusive circular economy, could bring much-needed credibility to the sector if deployed at scale.

This momentum indicates that investors are increasingly ready to move. “Policy support is growing, and more regulation means more certainty,” says Khangzhen Leow, senior sustainability analyst at Lombard Odier Investment Managers. “Consumers are more aware and willing to pay a premium to support more circular products. The convergence of factors makes it possible for investors to operate a profitable business”. Lombard Odier has launched a circular plastic fund in partnership with the Alliance to End Plastic Waste to foster financial research in this emerging space.

As activity in the circular plastics economy grows, institutional investors like Blackrock are more inclined to diversify their investments in packaging, chemicals or fast-moving consumer goods towards those that accelerate the transition. By the end of June 2021, 13 public equity funds focused on the circular economy had a combined US$8bn in assets under management—signalling to investors and companies that the transition is well under way and that early movers stand to benefit the most.

Allocating funds to the circular plastics economy is a critical piece of the puzzle. Deploying it where it is needed is quite another. “Investors tend to focus on capital expenditures, such as tangible infrastructure, but the system beyond the facility itself is heavily underfunded,” says Helga Vanthournout, who is an advisor at ADM Capital Foundation. “Collection infrastructure and logistics are all part of a working recycling system and are as important, if not more, but due to their more fragmented and inherently messier nature, don’t rate as highly on an investor’s agenda.”

For advocates who believe that the plastics industry is ripe for disruption, a plastics credit market could offer a way to unlock additional capital. A company buying a volume of credits equivalent to its plastic footprint could help meet the short-term need of paying to remove plastic from the environment while potentially financing the CAPEX and OPEX requirements of a circular plastics economy.

“Buying into a credit programme can turn corporate pledges into the capital and operational expenditure needed to build out the infrastructure and support the communities that engage in waste management activities”, claims Sebastian DiGrande, chief executive of the Plastic Credit Exchange (PCX). “If the private sector understands what it takes to get more quality feedstock, then it can help fund the journey to get there.”

Where ESG and plastics meet

Clear and standardised disclosure requirements will be critical to unlocking capital and must be baked into the treaty, according to our interviewees. Only then can risks be adequately understood and mitigated, investments and best practices deployed at scale and recycled plastics traded globally.

Standardised ESG data for the plastics industry could go a long way to nudge investors currently on the fence. ESG assets are expected to surpass US$50trn by 2025, but at the same time, the number of private investors taking ESG considerations into their investment decisions is down by 5% over the last year. Clearer and more robust ESG standards could help unlock further capital and push companies to be more transparent and ambitious with their sustainability goals.

Getting accurate and useful ESG data and disclosure from public companies is challenging. Getting it from private entities will be harder still. “We are clearly articulating our expectations to the companies in our fund,” says Eugenie Mathieu, senior impact analyst and earth pillar lead at Aviva Investors. “For one of the car manufacturers, for example, we’ve asked them to increase the recyclability of their EV [electric vehicle] batteries and the recycled content in their cars. But other companies choose to disclose what they want to disclose. A majority of companies are still pretty slow.”

Companies that strengthen their ESG performance will be better prepared to adapt to emerging regulations, attract consumers who are mindful of the impact of plastics and attract ESG investment to support more innovation along the plastics supply chain. “Companies must start reporting on the same set of indicators so that we, as investors, can start comparing them more effectively,” says Ms Mathieu.

ESG investing alone cannot solve the plastics crisis or address market failures, but the processes that underpin ESG can greatly improve the robustness of the investment process and support the development of a more investable and transparent pipeline of projects.

Where does that leave the treaty?

Besides creating the standards for a new plastics economy, the treaty is a unique opportunity to define the rules of the investment game. Treaty negotiators should assess existing financial instruments and be creative in developing new ones, where risk is shared, and returns and impact are measured and verified.

According to Ms Martin, “the solutions are out there, the financing is available, and there are many examples of successful initiatives across individual markets. The treaty will have to establish global standards that can help increase transparency in this sector, scale local initiatives and ensure that they can perform at a global stage.”

There is no shortage of money. Investors increasingly recognise that the circular plastics economy transition is under way and that first movers will see economic gains. Market dynamics are shifting, but not fast enough to address the plastic pollution crisis.

Interviewees:

- Sebastian DiGrande, chief executive, Plastic Credit Exchange (PCX)

- Khangzhen Leow, senior sustainability analyst, Lombard Odier Investment Managers

- Ellen Martin, chief impact officer, Circulate Capital

- Eugenie Mathieu, senior impact analyst and earth pillar lead, Aviva Investors

- Jacob Rognhaug, vice president for public affairs system design, Tomra

- Yonathan Shiran, partner and plastics lead, Systemiq

- Helga Vanthournout, advisor, ADM Capital Foundation

THANK YOU

Thank you for your interest in Back to Blue, please feel free to explore our content.

CONTACT THE BACK TO BLUE TEAM

If you would like to co-design the Back to Blue roadmap or have feedback on content, events, editorial or media-related feedback, please fill out the form below. Thank you.