Japan’s chemical industry has been shaped by a marine pollution tragedy. The lessons garnered from this transformed the nation’s view of environmental protection—but how much have they been truly absorbed?

As the world’s third-largest chemicals producer by shipments, Japan carries considerable weight in the future of efforts to reduce marine pollution. This is not only due to the size of its industry, though. For decades, Japan and its industrial groups have played a leading role in the economic development of Asia, where the chemicals industry is shifting fast. At both the public and the private level, Japan can play a major part in driving a global push to reduce marine pollution.

Japan’s significance also stems from its poignant historical lessons. Unlike most countries that have yet to grapple with marine chemical pollution, Japan has a painful experience of ocean poisoning that profoundly shaped the course of its chemical sector—and its overall relationship with the environment. In the 1950-60s a chemical company’s discharge of mercury into Minamata Bay afflicted thousands of people with a debilitating neurological disorder. The national and local government covered up the scandal for years, refusing to attribute “Minamata disease” to industrial effluent.

According to Dr Naoko Ishii, director of the Center for Global Commons at the University of Tokyo, a “develop now, clean up later” culture that defined Japan’s post-war economic miracle left a trail of ecological travesty that is epitomised by Minamata. The scandal holds particular relevance today, as Asia’s emerging countries—fast growing as chemical powers—confront their own trade-offs between rapid development and environmental stewardship.

“One thing that we can learn from Minamata is the dark side of a history of ‘develop now-clean up later,’” says Dr Ishii, whose centre focuses on socioeconomic system transformation. “Depending on the development stage of each country, there are still countries which prioritise economic growth over people’s health or safety.”

Japan’s own record since Minamata has been mixed. As evidence mounted of a catastrophic human cost—and Japan’s economy reached maturity—a strong consensus formed around environmental protection. Today, Japan can boast some of the most stringent industrial effluent standards in the world. Yet its chemical companies still only garner average scores in global rankings of chemical responsibility.

And according to Dr Ishii, there are significant blindspots. These include overusing chemical fertilisers such as nitrogen and phosphate that—unknown to the general public—seep from land to rivers and into Japan’s seas, posing a grave threat to the ocean environment.

Industry snapshot

The chemicals sector plays an outsized role in Japan, the world’s third-largest economy. Its actions therefore carry major impacts on sustainability both at home and abroad.

The sector is Japan’s second-largest industry in value terms and the third-largest employer.

The industry’s top five producers—Mitsubishi Chemical, Toray Industries, Sumitomo Chemical, Shin-etsu Chemicals, and Mitsui Chemicals—together generate more than US$86bn in revenue and rank among the top 25 chemicals players in the world.

In terms of sustainability performance, energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie sees Japan’s chemical companies as “broadly representative” of the global industry. Japan’s big three firms, Mitsubishi, Toray and Sumitomo, receive marks of C, C and C- respectively in ChemScore’s rankings of the world’s top 50 responsible chemicals companies. Toray ranks 6th globally, while Mitsubishi comes in 9th and Sumitomo at 16th.

Despite its global weight, Japan’s chemistry industry is also seen to be in decline in the critical field of commodity chemicals, where Asian players are fast rising. “Japan … is now in a period of structural stagnation in the world of commodity chemicals,” says Kelly Cui, who is the principal consultant for the Wood Mackenzie Chemical Team. “For major polymers and their intermediates, we forecast production in Japan will decline by 12% between 2020 and 2050, while global production will grow by nearly 80% in the same period.”

That means Japan’s main avenue for growth will come from value-added specialty solutions to global clients in the industrial sector. Today this increasingly means innovation leadership in sustainable chemicals and net-zero innovation—both for business and environmental priorities.

“It is extremely important for the Japanese chemical industry to maintain its global competitiveness,” the Japan Chemical Industry Association says in its Stance on Carbon Neutrality. “Toward this goal, the chemical industry will accelerate its measures to further advance processes and contribute to reducing GHG (greenhouse gas) emissions derived from energy and materials by developing technologies for CCU [carbon capture and utilisation], artificial photosynthesis, [and] chemical recycling.”

According to Wood Mackenzie, one promising area for Japan is research into captured carbon as a feedstock for the petrochemicals sector. Chemicals firm Tokuyama Corporation and Mitsubishi Gas Chemical recently signed a memorandum of understanding to explore the production of methanol in this way. In addition, the University of Toyama has developed a technology to produce p-xylene (an important chemical feedstock) via the same method.

“With its heritage of innovation,” says Ms Cui, “it is clear that taking a lead in developing sustainable chemicals provides one of the major opportunities for Japan’s chemical sector to find a niche that is beneficial for the sector and for the planet.”

Will Japan succeed? The past holds some important clues.

Lessons from Minamata

The legacy of Minamata is somewhat ambiguous. In the face of overwhelming evidence of government misconduct, it took until 2004 for a Supreme Court in Osaka to recognise official responsibility and grant compensation. Yet long before the ruling, the tragedy galvanised action at the government, business and community level on the urgency of environmental protection.

A turning point came in 1971. A water pollution control law took effect that went on to yield some of the world’s most stringent controls on industrial chemical effluent. For example, Japan today limits effluent of cadmium, a toxic metal, to 0.03 mg/L, which is far stricter than the US Environmental Protection Agency’s upper limit of 1.2 mg/L.

“There were huge issues that arose from Japan’s post-war industrial development. Among them were severe problems of water pollution from industrial effluent,” says Kenichiro Mawatari, head of the Green Transformation Unit of Mitsubishi Chemical. “Learning the lessons of improper environmental actions in our chemistry sector led Japan to enact extremely stringent safety standards across the chemicals industry.”

In the new mission of sustainable development, Japan’s chemical sector became a pioneer in solutions for environmental stewardship. This includes advanced nano-filtration membranes developed by Mitsubishi Chemical and Toray Industries that can catch chemicals before they enter the ocean. A promising new direction is evident in the fact that chemical giants are teaming up with green chemistry start-ups to develop chemicals from biomass for sustainability strategies.

One prominent example is a Mitsui Chemicals collaboration with start-up Green Earth Institute to develop a raw material for a biomass-derived version of polypropylene. This polymer used in containers and packaging materials accounts for 20% of all plastics produced in Japan.

“A strength of the Japanese chemical industry comes from its accumulated experience in solving various problems in the past,” says Steve Jenkins, who is vice-president for the Wood Mackenzie Chemical Team. “Japan’s chemical sector thereby gains major strengths as a solution provider, particularly in the areas of developing environmental solutions.”

A chemical blindspot

Amid environmental advances, Japan’s most serious chemicals problem—as relates to marine pollution—may lie in its food supply. Specifically this means over-reliance on chemical fertilisers that seep into rivers and eventually the ocean.

According to a paper in the peer-reviewed journal Environmental Pollution, Japan and South Korea have the highest levels agricultural nitrogen and phosphorus overuse among OECD member countries—“thus both countries are primarily responsible for severe environmental pollution via nutrient release.”

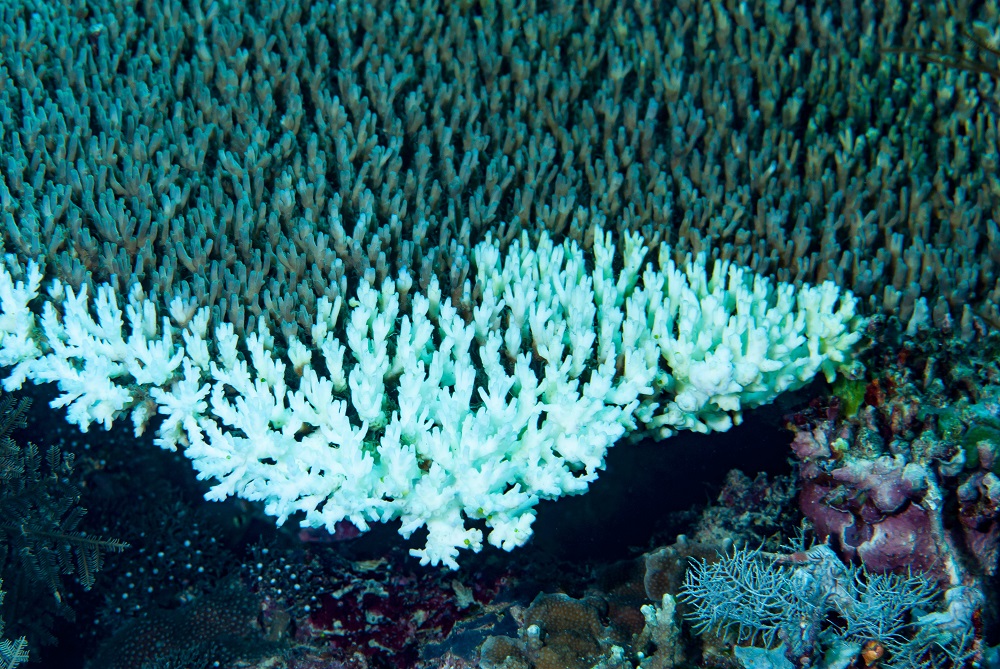

“In Japan, due to over-fertilisation there is a lot of chemical fertiliser that is not taken up by plants,” says Dr Ishii. “From land, it goes into rivers and then into the oceans. That creates a huge pollution issue and damages the health of the ocean.”

Last year, Japan’s Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries enacted a Sustainable Food Systems blueprint that mandates a 30% reduction in chemical fertiliser use and a 50% reduction in the “risk-weighted” use of chemical pesticides by 2050. Dr Ishii calls the policy “highly significant”, and adds that “due to political pressure, it’s not easy to implement or materialise the mission in a straightforward manner.”

Alliances across the value-chain

Ultimately, Japan’s success in greening its chemical sector will depend upon forging alliances for sustainability across the chemical sector value chain. That means co-ordination from upstream chemical companies and suppliers down to manufacturers, retailers and ultimately end-users. Obtaining consumer buy-in is essential, as they can “vote with their wallet” to influence business priorities.

A promising step came in 2019 with the formation of the Japan Clean Ocean Material Alliance (CLOMA), an industry group promoting the elimination of ocean plastic waste. Comprising 425 members across the industrial value chain, CLOMA supports collaboration on advanced technologies for chemical recycling, material recycling and biodegradable plastics.

According to Wood Mackenzie’s Mr Jenkins, research and development into chemical and material recycling represents the “low-hanging fruit” in Japan for promoting a sustainable chemicals industry.

“There is plenty of opportunity to develop recycling to produce more sustainable feedstocks in Japan,” says Mr Jenkins. “We see the amount of packaging going to recycling rising by 50% over the next 20 years.”

To succeed, CLOMA’s chief technology officer, Koichi Yanagita, says that businesses must co-ordinate to mitigate first-mover disadvantage and create a business logic for achieving sustainability gains in the chemicals industry.

“Industries need to come together across the value chain to make environmentally friendly practices cost-effective for all stakeholders,” says Mr Yanagita. “We need to discover ways to implement sustainable practices that absorb costs and enable profit on the business side. This will be the way forward.”

Back to Blue is an initiative of Economist Impact and The Nippon Foundation

Back to Blue explores evidence-based approaches and solutions to the pressing issues faced by the ocean, to restoring ocean health and promoting sustainability. Sign up to our monthly Back to Blue newsletter to keep updated with the latest news, research and events from Back to Blue and Economist Impact.

The Economist Group is a global organisation and operates a strict privacy policy around the world.

Please see our privacy policy here.

THANK YOU

Thank you for your interest in Back to Blue, please feel free to explore our content.

CONTACT THE BACK TO BLUE TEAM

If you would like to co-design the Back to Blue roadmap or have feedback on content, events, editorial or media-related feedback, please fill out the form below. Thank you.

The Economist Group is a global organisation and operates a strict privacy policy around the world.

Please see our privacy policy here.

World Ocean Summit & Expo

2025

World Ocean Summit & Expo

2025 UNOC

UNOC Sewage and wastewater pollution 101

Sewage and wastewater pollution 101 Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution

Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC

Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC