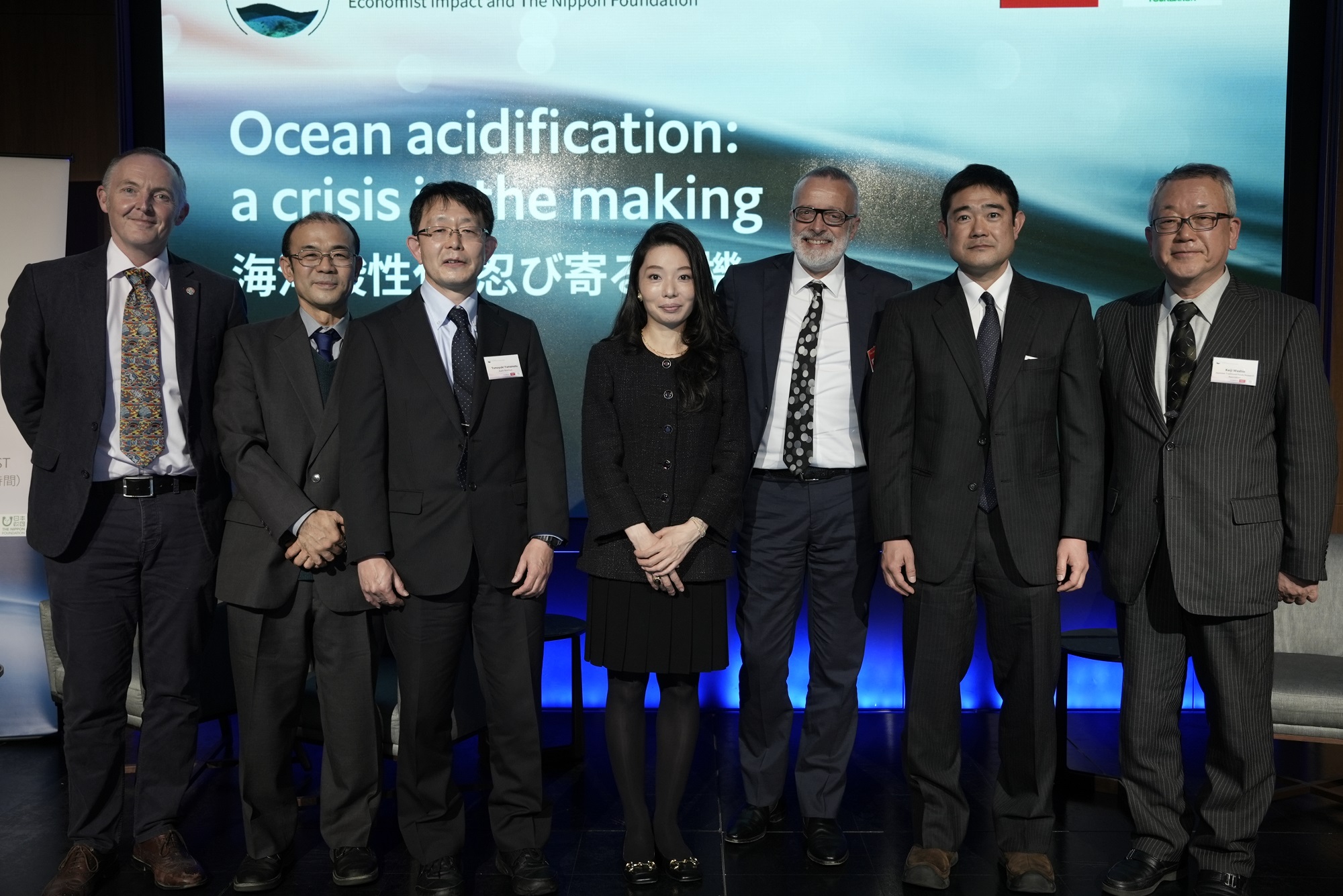

Back to Blue hosted an event on ocean acidification on February 2nd at the Grand Hyatt, Tokyo, which was joined by audiences from 95 countries. The chairman of The Nippon Foundation, Yohei Sasakawa, and the chairman of The Economist Group, Lord Deighton, made opening remarks, inviting the audience and media to participate in the discussions around what we can do to avoid the worst impacts of ocean acidification. It also premiered a short documentary on ocean acidification, The threat bubbling up, created by Economist Films.

Panelists included Steve Widdicombe, scientific director of Plymouth Marine Laboratory, a world authority on marine ecology, and Japanese fisheries researchers. Peter Thomson, the UN special envoy for oceans, said, “In light of the biodiversity framework adopted at the end of last year, ocean acidification is an urgent issue. Today’s event is very significant. This year, the G7 meeting will be held in Japan, a maritime nation. I hope that Japan will show leadership in this regard.”

From the left: Steve Widdicombe (director of science, Plymouth Marine Laboratory), Tsuneo Ono (chief scientist of marine environment, Japan Fisheries Research and Education Agency), Tomoyuki Yamamoto (science journalist, Asahi Shimbun) and Naka Kondo (Economist Impact).

From the right: Keiji Washio (chairman, Japanese Traditional Foods Research Association), Masahiko Fujii (associate professor, faculty of environmental earth science, Hokkaido University) and Charles Goddard (Economist Impact).

Back to Blue released its Ocean Acidification programme in December 2022. The report focuses on the need to address ocean acidification and is based on the insights and research provided by some of the world’s leading ocean scientists. The report highlights how time is rapidly running out to avoid the worst effects of ocean acidification on marine life, livelihoods and economies.

Ocean acidification occurs when seawater absorbs the carbon dioxide generated by human activities such as burning fossil fuels. More than a quarter of the carbon dioxide emitted by humans into the atmosphere has been absorbed by the oceans each year, but such emissions are now increasing so rapidly that the oceans are no longer able to absorb it. As a result, the chemistry of the ocean is changing, acidity is increasing, and the ability of many marine organisms to protect themselves, grow and reproduce is weakening.

“We have enough knowledge to develop effective means to mitigate and adapt to the effects of acidification. Development of ocean resilience is a challenge that cannot wait. It will be costly, but we believe it must be weighed against the benefits of avoiding future damage.”

– Charles Goddard, editorial director, Economist Impact

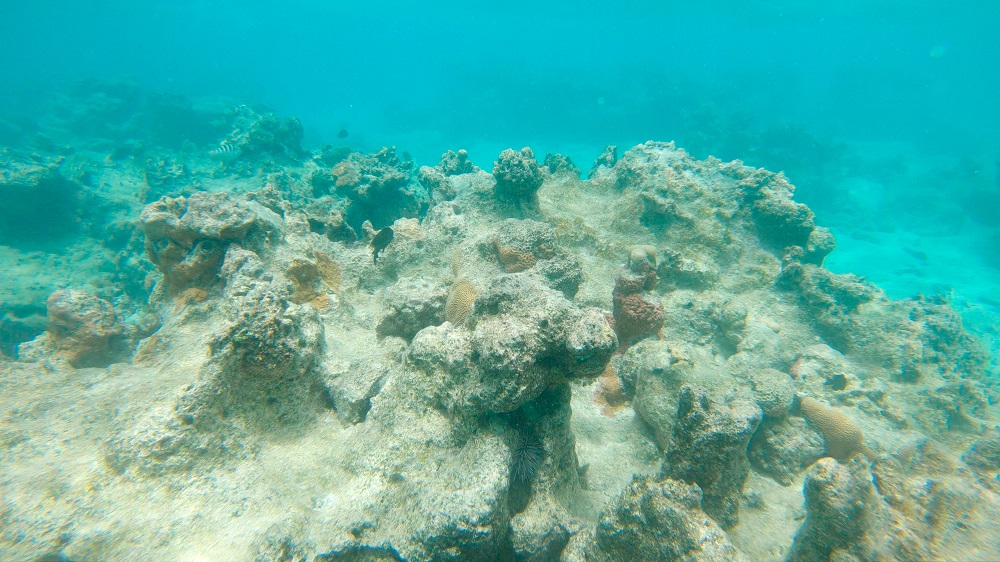

The report points out that if current high emissions continue, many marine organisms, including mollusks, pteropods, also known as “butterflies of the sea”, and warm-water corals, will be at very high risk from acidification as early as 2050. The negative impacts on marine biodiversity and the marine food chain due to the decline of these organisms are likely to be severe.

Mr Widdicombe, who is also the co-ordinator of the Ocean Acidification Research for Sustainabilit programme, remarked, “Ocean acidification, warming and deoxygenation are interacting to create the perfect storm of environmental problems.”

The continuing impact of ocean acidification on seagrass beds, coral reefs, and marine life means that we are treating the ocean, which provides more than half of the oxygen we breathe and is one of our most valuable defenses in the fight against climate change, in an economically and ecologically devastating manner. It is time to make ocean acidification a top priority so that we can more proactively develop a scientific understanding of its impacts and promote necessary response and adaptation measures globally before it is too late.

– Yohei Sasakawa, chairman, The Nippon Foundation

The programme also shows some of the potential economic impacts of ocean acidification that have not yet been extensively studied. If ocean acidification is not addressed, coastal economies and the aquaculture, tourism and other jobs that depend on them will be at significant risk. Past estimates of economic losses from reduced shellfish production alone range from US$75m in the US to over US$1bn in Europe. In many parts of the Southern Hemisphere, where fisheries and aquaculture contribute tens of billions of dollars to local economies and employ millions of people, the impact of acidification on livelihoods is very serious.

While the best way to avoid the most severe effects of ocean acidification is to dramatically reduce carbon dioxide emissions, the report also highlights other measures that can mitigate its impacts. For example, marine reserves are protected areas set aside by governments with limited human impacts that can be made “climate smart” by using them to develop ways to mitigate or adapt to the effects of ocean warming and acidification. Technology is also being developed to extract carbon directly from seawater. And solutions using nature, such as blue carbon habitats, can reduce the amount of carbon absorbed by the oceans and reduce ocean acidification.

THE SUSTAINABILITY PROJECT

WORLD OCEAN INITIATIVE

WE LOVE TO HEAR FROM YOU

We welcome your feedback and comments.

If you have an editorial or media related request, a member of the media team will get back to you.

EXPLORE MORE CONTENT ABOUT THE OCEAN

THANK YOU

Thank you for your interest in Back to Blue, please feel free to explore our content.

CONTACT THE BACK TO BLUE TEAM

If you would like to co-design the Back to Blue roadmap or have feedback on content, events, editorial or media-related feedback, please fill out the form below. Thank you.