Charles Darwin once dismissed the ocean as a “tedious waste, a desert of water”. Yet some of his contemporaries disagreed. The Challenger expedition of the 1870s set out to discover what lurked beneath, traversing over 100,000 km on a wooden, steam-assisted vessel with a team living on biscuits and cocoa. They found 4,772 specimens, from sea snails to snake eels, discovered earth’s deepest trench, and toppled false assumptions about the lack of life under the waves.

Over a century later, the Census of Marine Life picked up the baton. An 80-country collaboration, with 2,700 scientists, the project identified another 6,000 species. Yet even these numbers are a literal drop in the ocean. The total library of known marine species stands at 240,000, but estimates put the real figure at 2.2 million at the least. The rate of discovery, around 2,000 per year, has barely changed since the Victorian era.

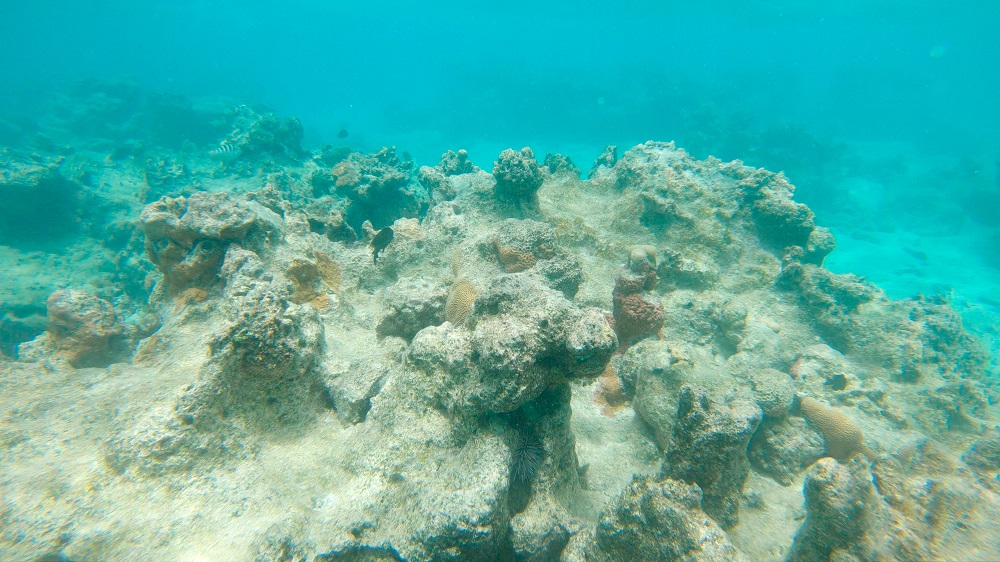

A new mission, the Ocean Census, launched in April this year with a far greater ambition: to find at least 100,000 new marine species in its first decade. This reflects an urgency that earlier voyagers lacked. Warming water and oxygen depletion portend a mass extinction event for marine biodiversity. This is a make-or-break decade to identify as much marine life as we can, to better protect it. The first ship, a Norwegian icebreaker, ventured into the Barents sea in late April.

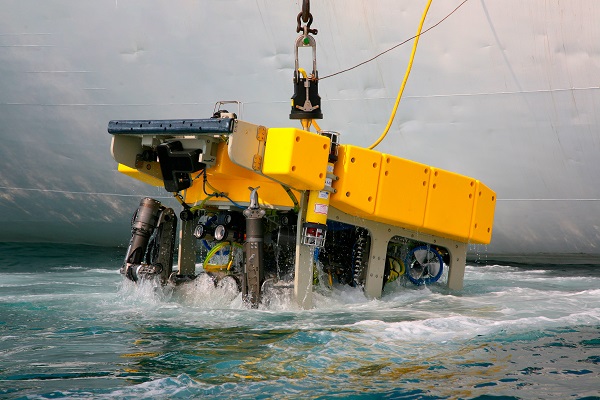

The initiative, founded by the Nippon Foundation and Nekton, will deploy more advanced technologies, from sea-faring vessels, subsea technology and undersea robots to classification powered by artificial intelligence (AI), operating through a global network of experts, participation institutions and citizen scientists. “There is great urgency to discover what lives in our oceans so that we can use that information, that data, to inform sustainable management governance and unlock a deeper understanding of what ocean life is all about,” says Oliver Steeds OBE, the project’s director.

A former investigative journalist for organisations such as ABC, Channel 4, Discovery and Al Jazeera, Mr Steeds became passionate about this concern during an investigation on a marine protection area in Scotland. “It was like a lush jungle underwater. Outside of that, it had been trawled for scallop fishing and it was a desert. It was visually striking and deeply sad to witness what was going on,” he told Back to Blue. “I realised the ocean was the beating heart of our planet and the least understood. I decided if there was something I could contribute to a better future, then I should look to the ocean.”

The mission is not one of mere curiosity. It is existential. The ocean, Mr Steeds argues, “makes all life possible. It helps produce our oxygen and regulates our climate and chemistry, and provides food for billions of people.” Some of the most vulnerable ocean regions are the most critical for food security, such as the north Pacific and tropical Indo-Pacific, home to fisheries providing one-fifth of humanity’s dietary protein.

The ocean is already changing. Surface sea temperatures in the North Atlantic recently broke the previous record by another 0.5°C. The US east coast has seen extremes of over 10°C recently, says Mr Steeds, and the Indian Ocean is warming three times faster than the Pacific. Half of the world’s coral reefs, home to a quarter of all ocean species, have been lost. “There is an urgent need to discover species before they are lost from the heat and the twin evil brother of acidification. Now, more than ever, we need to know what lives in the ocean” he argues. Revealing the richness of marine life could serve to strengthen public interest in ocean protection.

Cyber taxonomy

Similar in approach to the Census of Marine Life, Ocean Census is an open network of scientists and other partners from government, philanthropy, business, media and civil society coming together to take on this global challenge. Scientists from research institutes around the world are uniting to expand marine species knowledge through innovations in navigation, like more advanced sea and subsea vessels and robotics; discovery, through high-resolution digital imaging; and classification, with sequencing and analysis, backed by AI. “In combination, this will create a new approach to identifying and describing species that we call cyber taxonomy,” says Mr Steeds.

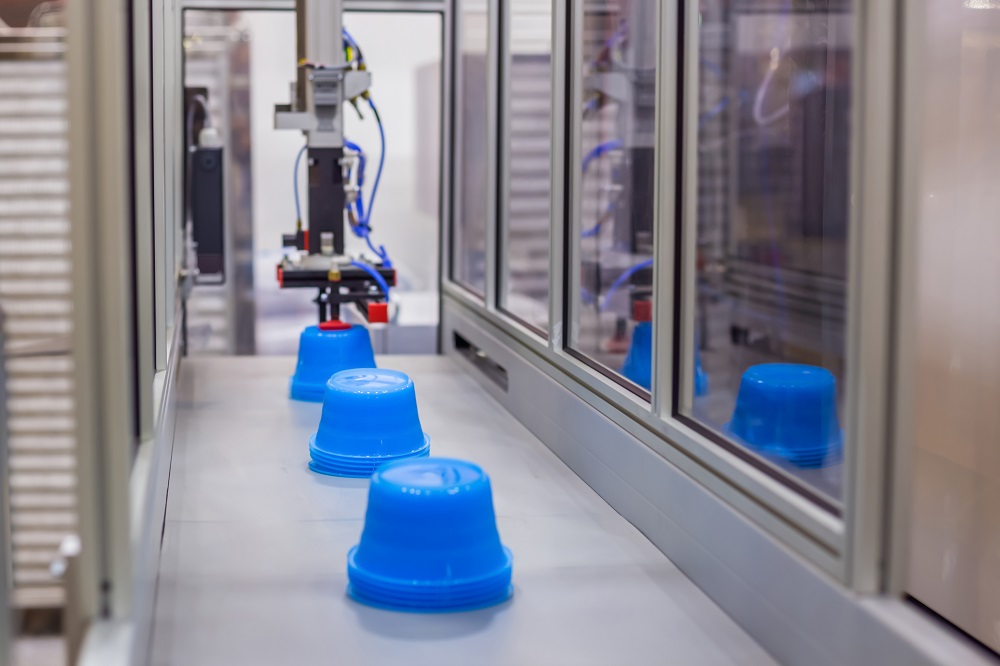

The approach will automate once time-consuming processes, such as entering DNA sequences into machine learning algorithms that can flag a new species. It could be less disruptive. Improved camera technologies mean that observers can scan marine species via laser to avoid removing them from their habitat.

The project has an expansive cast of participants and assets. Vessels will come from philanthropic, government and commercial fleets. The team will work across boundaries of discipline and geography, including engaging citizen scientists like scuba divers. “We’ve seen how valuable citizen scientists can be in monitoring insect populations on land, for example, and how that has transformed our understanding of the decline of insect populations like bees,” says Mr Steeds.

He hopes that Ocean Census will build long-term capacity too. Many taxonomists are nearing retirement age, and taxonomy is an under-funded discipline. Much marine biodiversity is situated in low- and middle-income countries with few taxonomists of their own. Ocean Census will set up imaging and DNA sequencing through biodiversity centres in nations around the world and aggregated and open-source data will be available to scientists, decision-makers and the public.

“For people to manage their ocean, they need those skills. One legacy of the project is building that knowledge and technology in low- and middle-income countries so we can get to a point where we can continue to discover and monitor what lives in our ocean,” says Mr Steeds. Data generated from territorial waters will be owned by host nations who can determine how to use and manage it, with recommendations from the Ocean Census team.

The Ocean Census comes at a moment when policy commitment to protect the ocean has never been stronger. The 2022 Montreal Biodiversity Conference culminated in a pledge to protect 30% of the planet for conservation by 2030. That requires much better data on the current and evolving state of marine life that Ocean Census can help provide. The UN Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction treaty in March 2023 provided an ambitious legal framework to establish protected areas in the high seas. Knowing the full richness of life underwater should only strengthen our desire to protect it.

THE SUSTAINABILITY PROJECT

WORLD OCEAN INITIATIVE

WE LOVE TO HEAR FROM YOU

We welcome your feedback and comments.

If you have an editorial or media related request, a member of the media team will get back to you.

EXPLORE MORE CONTENT ABOUT THE OCEAN

THANK YOU

Thank you for your interest in Back to Blue, please feel free to explore our content.

CONTACT THE BACK TO BLUE TEAM

If you would like to co-design the Back to Blue roadmap or have feedback on content, events, editorial or media-related feedback, please fill out the form below. Thank you.