Professor Kenneth Leung

Director of the State Key Laboratory of Marine Pollution

Professor Kenneth Leung, Director of the State Key Laboratory of Marine Pollution in Hong Kong, tells Back to Blue about his work studying pharmaceutical pollution in rivers and estuaries. Active chemical ingredients from the pharmaceutical industry are present in waterways across the world, and solutions, from policies to high-tech treatments, are needed to stem the tide of environmental harm.

What has your research revealed about pharmaceutical pollution in estuaries and marine ecosystems?

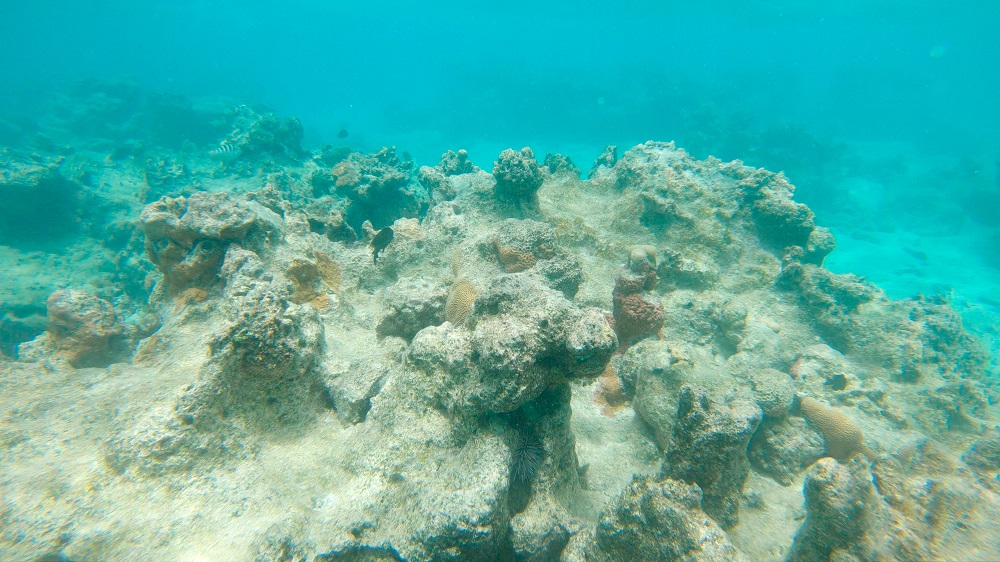

Pharmaceuticals are created with active chemical ingredients to target specific diseases in humans or in farm animals. However, the concentrations of active chemicals required to make medicines can have a negative impact on wildlife. Additionally, many of these chemicals can’t be removed by conventional sewage treatment plants. As a result, some are very persistent in the environment, so they accumulate in sediments and reach increasingly high concentrations.

Between 2018 and 2021, I co-led a study on pharmaceuticals in rivers led by Professor Alistair Boxall at the University of York; the project covered 258 rivers worldwide, a third of which had never been studied before. We created sampling kits and sent them to interested participants to help with sampling along pollution gradients from clean upstream water to polluted downstream areas, covering over 1,000 sampling sites. We found that all rivers but two contained pharmaceuticals, meaning pharmaceutical pollution is extremely widespread. Most alarmingly, about 26% of the rivers had concentrations of pharmaceuticals exceeding safety limits. This includes antibiotics that may trigger antibiotic resistance in microbial communities, and chemicals that cause growth retardation or behavioural changes in fish and other aquatic life. For example, high concentrations of chemicals found in antidepressants may increase the chance of fish being eaten by predators. We also found that pollution levels were higher in low- to middle-income countries, those which have access to medicines but lack the infrastructure and policies to properly treat waste and wastewater. This is a global problem, as river water eventually flows into estuaries and then the ocean, where it impacts every country’s marine environment.

In response to our findings, we submitted a proposal to the United Nations in 2020 to continue our work on ocean science and sustainable development. The UN endorsed our Global Estuarine Monitoring (GEM) Program as part of the UN Decade of Ocean Science. We launched the project in 2022 after setting up standard methods and sampling kits; we now have more than 120 scientists involved worldwide, covering over 150 estuaries. We’ve analysed about 60 estuaries so far at our laboratory at City University of Hong Kong, all of which contained pharmaceuticals.

Can you tell us more about the GEM project and its role in the UN Decade of Ocean Science?

The slogan for the Ocean Decade is: “The science we need for the ocean we want.” This means we shouldn’t do science just for the sake of publication, but rather aim to have a transformative impact; our research should ultimately translate into action for improving the ocean. With this as our motivation, we’re excited to continue working on pollution in rivers and estuaries with the University of York, building on our previous work. In the second phase of the project, we’ll expand the range of pollutants we study beyond medicines and look at flame retardants like PFAS, as well as UV filters and e-waste-related materials. We’ll cover a much wider range of pollutants that have been understudied before, and we now have the capacity to understand the situation of these pollutants on a global scale for the first time. Since pollutants in estuaries may be in lower concentrations after being diluted with seawater, we’re developing passive sampling systems using new materials that can absorb different types of organic pollutants, allowing us to gather them in high concentrations. Using the same method across sites, we can get a comprehensive understanding of the global situation, with profound implications for environmental management.

What are the potential solutions, and how should governments and international organisations go about addressing the issue?

We believe solutions can range from simple policies to high-tech treatments. For example, in some African and Asian countries, open dumping of waste and wastewater in lagoons has led to pollutants being released into river systems and the ocean during heavy rains. Building more septic tanks can be a simple and cheap solution to this problem, and international organisations like the World Bank should contribute by investing in more green infrastructure in these countries. Additionally, people should stop flushing unused or expired medications down the toilet, as these chemicals end up in waterways. The US has a compulsory system for collecting medicines at police stations, and Australia has a similar voluntary system; encouraging more governments to adopt these centralised collection systems can help motivate more people to think twice before flushing medicines. There are also more advanced treatment systems made possible by ongoing scientific and technological advancements, like upgrading secondary treatment to tertiary treatment in wastewater plants. These solutions are feasible, but their implementation requires globally co-ordinated efforts.

What responsibility does the pharmaceutical industry have for managing medicines once they’re in the hands of consumers, and have they been engaging with solutions to the pollution problem?

The chemical and pharmaceutical industries are increasingly recognising the importance of green chemistry, which means they’re working on releasing fewer pollutants during the production process and ensuring final products are biodegradable to an extent. However, to ensure efficacy and effectiveness, some drugs still require the use of persistent and potentially toxic chemicals. In these circumstances, we need to optimise their use and reduce it when possible. For example, many developing countries issue antibiotics over the counter, meaning there is less control over their use and disposal. We must make sure antibiotics are only prescribed when they’re genuinely needed. This is also an issue for the World Health Organization, as they are dealing with antimicrobial resistance, which is worsened by the overprescription of antibiotics. Currently, about 5 million people die each year due to superbugs, and projections suggest this number might increase significantly. We need to use antibiotics more sensibly and implement appropriate control measures, as well as working with pharmaceutical companies to find more environmentally friendly replacements. This will require a risk management-based approach, which involves considering a multitude of factors such as usage amounts, discharge levels, persistency, toxicity and bioaccumulation potential. It’s also important to improve regulation for animal medicines, which are currently less regulated than human medicines and still cause harm to humans and wildlife when discharged into the environment.

EXPLORE MORE CONTENT ABOUT THE OCEAN

THANK YOU

Thank you for your interest in Back to Blue, please feel free to explore our content.

CONTACT THE BACK TO BLUE TEAM

If you would like to co-design the Back to Blue roadmap or have feedback on content, events, editorial or media-related feedback, please fill out the form below. Thank you.