From food packaging to smartphones, home insulation to electric vehicles, plastic is an essential material for everyday life. However, plastic pollution especially in our freshwater system and the oceans has sparked a public backlash as rapid production of disposable plastic products overwhelms the world’s ability to deal with them.

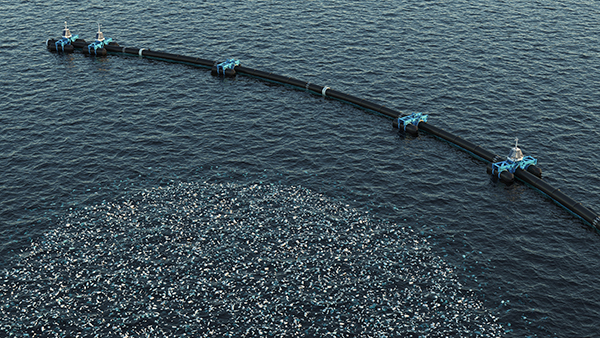

Images of fish, dolphins or seahorses entangled in plastic waste make for arresting visuals but it’s the ingestion of plastic by fish, mammals and humans that poses the more severe threat. Microplastics,

tiny particles of less than five millimetres that break off from clothing, car tyres, or personal care items, to name a few, are ending up in our food, water and air, causing harm to metabolic health and immunity and even increasing cancer risk.

Microplastics, tiny particles of less than five millimetres, are ending up in our food, water and air, causing harm to metabolic health and immunity and even increasing cancer risk.

While recognising that we are dealing with a plastics crisis is a critical first step, tackling this issue is in fact a lot harder. The very qualities that make plastic ubiquitous – low cost, lightness, malleability – have deeply entrenched a throw-away culture with single use plastics accounting for at least 40% of plastics produced every year. Due to its low cost, people are not invested in reusing and recycling the plastic products and because of their properties, they do not biodegrade as well.

Governments and industries must fight plastic waste together

Popularly touted solutions often fall short. Recycling cannot significantly tackle the problem, partly because current technology can only process a narrow range of simple plastic products, partly because the industry has poor governance, with many cases of plastic recycling simply sent to incinerators or landfills.

On the other extreme, calls for ‘zero plastic’ are unrealistic. Few materials compete with plastics in terms of breadth of application and some suggested alternative materials, like cardboard or glass, are far from environmentally friendly. Data suggests the entire lifecycle emissions of alternatives like glass and paper are higher.

What is needed is a holistic approach to material design and production through to disposal and reuse, with industry and government working together. This will require strong regulations to phase out harmful practices, as well as moves that encourage innovation and R&D into next-generation materials. To get there, we need to know how countries currently perform, and where the key obstacles lie.

Understanding how countries fare when it comes to plastics management

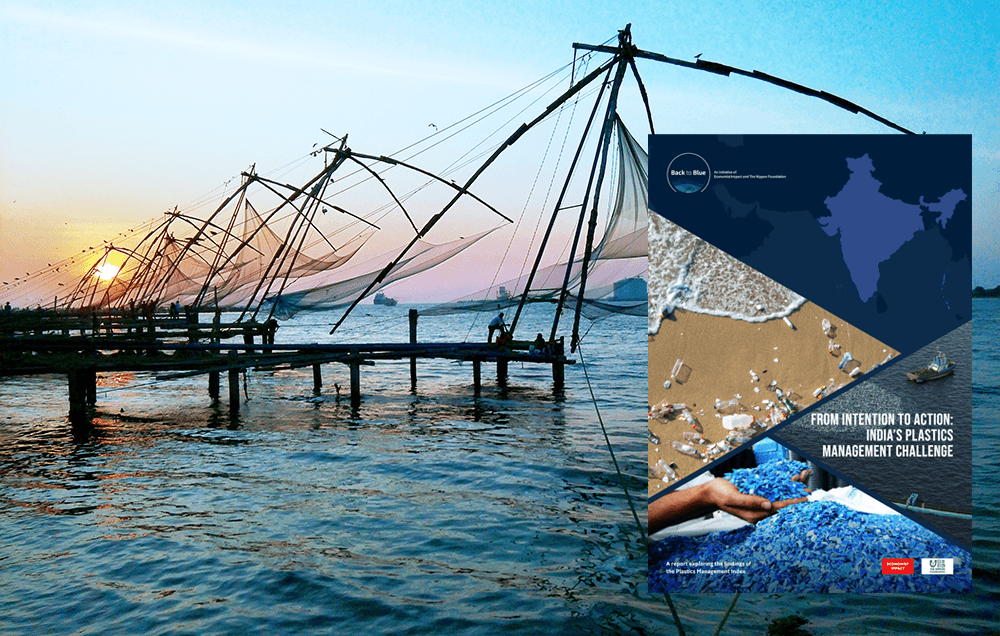

Economist Impact, part of The Economist Group, has worked with the Nippon Foundation to produce the landmark 2021 Plastic Management Index (PMI), ranking 25 countries across a series of indicators from policy and regulation to business and consumer practices and attitudes. The initiative, part of the Back to Blue collaboration between our two organisations, present a worrying picture – while also pointing to useful strategies and actions taken by the leading nations.

The PMI’s most concerning finding is that lower-middle income countries are struggling the most to manage plastics, and Asian nations are clustered in the middle of the index in terms of performance.

The PMI’s most concerning finding is that lower-middle income countries are struggling the most to manage plastics, and Asian nations are clustered in the middle of the index in terms of performance. This is a concern because of how much of the global plastics industry is centred in these nations – and this is set to grow in the future as they develop their economies. Over half of the plastic waste leaked in the world’s oceans originates from five countries, all in Asia (China, Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam). Our index found that the Middle East and Africa are struggling the most. Nigeria, Africa’s most populous nation, ranks bottom in three out of the four categories we measured.

Intention and the will to act matters no matter how wealthy or developed an economy is

But there is also cause for cautious optimism, as the index provides two useful insights. The first is revealing the countries that are leading the world and the reasons for their strong performance. Number-one ranked Germany, for instance, has achieved pole position thanks to a range of factors that include a consultative approach that works with businesses in the design of policies and programs, such as its successful recycling scheme, and strong national commitment evidenced through its efforts to put marine litter on the G20 and G7 agendas. No doubt Germany’s historically close ties between industry with government, and its highly developed manufacturing and chemicals industries, also provides a strong technical and political foundation for its leadership.

The PMI also shows that country performance is not strictly correlated to income level, GDP or industrial competitiveness.

But the PMI also shows that country performance is not strictly correlated to income level, GDP or industrial competitiveness. Vietnam, a lower middle-income country, outperforms every upper-middle income country except China in our ranking. Malaysia ranks top globally for responsible consumer actions and perceptions. Kenya beats Germany in an index category which assesses private sector commitment to responsible plastics use.

While the African nations as a whole are struggling, Ghana is a leading light for others to follow; uniquely for the continent’s countries that we assessed, it regulates single-use plastics and microplastics, requires the private sector to report on its plastics footprint, and promotes green public procurement. Conversely, the US, the richest country and largest economy in the index, only ranks 5th overall. Intention and the will to act – by governments, industry and consumers – matters more than how wealthy or developed an economy is.

The PMI’s goal is not to name and shame – instead, it provides the first rigorous benchmark of how well countries around the world are managing plastics, an essential commodity for modern life. This can help governments across the globe reliably assess their strengths and weaknesses, identify exemplar nations who they can learn from and, as the index renews in future years, track performance with the long-term objective of driving meaningful policy action and outcomes.

Naka Kondo is a Manager for Policy and Insights at Economist Impact, based in Tokyo.

Read more on the Plastic Management Index which examines plastic management through the lens of policy, regulation, business practice and consumer actions at a country level.

THANK YOU

Thank you for your interest in Back to Blue, please feel free to explore our content.

CONTACT THE BACK TO BLUE TEAM

If you would like to co-design the Back to Blue roadmap or have feedback on content, events, editorial or media-related feedback, please fill out the form below. Thank you.