As countries agree on an historic High Seas Treaty to preserve international waters, Back to Blue interviews Vladimir Ryabinin, the outgoing executive-secretary of the UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC), about recent progress on ocean governance and his hopes for the future.

Vladimir Ryabinin is feeling “cautiously optimistic—and this is indeed surprising.” It is not often that ocean scientists have been given cause for optimism. The ocean covers almost three-quarters of the Earth’s surface, supplying us with food, water and oxygen. It is also critical for combating climate change, as the ocean absorbs a quarter of the carbon dioxide emitted by humans, and supports the livelihoods of 3 billion people. Despite its importance, the ocean has been neglected by governments and side-lined from global climate negotiations, pushing its ecosystems close to collapse.

Recently, however, there has been progress, with countries reaching two major international deals. In December, UN member states hammered out an agreement to protect the ocean at a UN biodiversity summit in Montreal. The Kunming-Montreal global biodiversity framework set a goal to conserve 30% of the planet’s ocean and land by 2030 (known as the 30×30 goal). Then, on March 4th, countries agreed on the first ever treaty to safeguard international waters. The High Seas Treaty was almost two decades in the making. Without it, the 30×30 goal would have floundered.

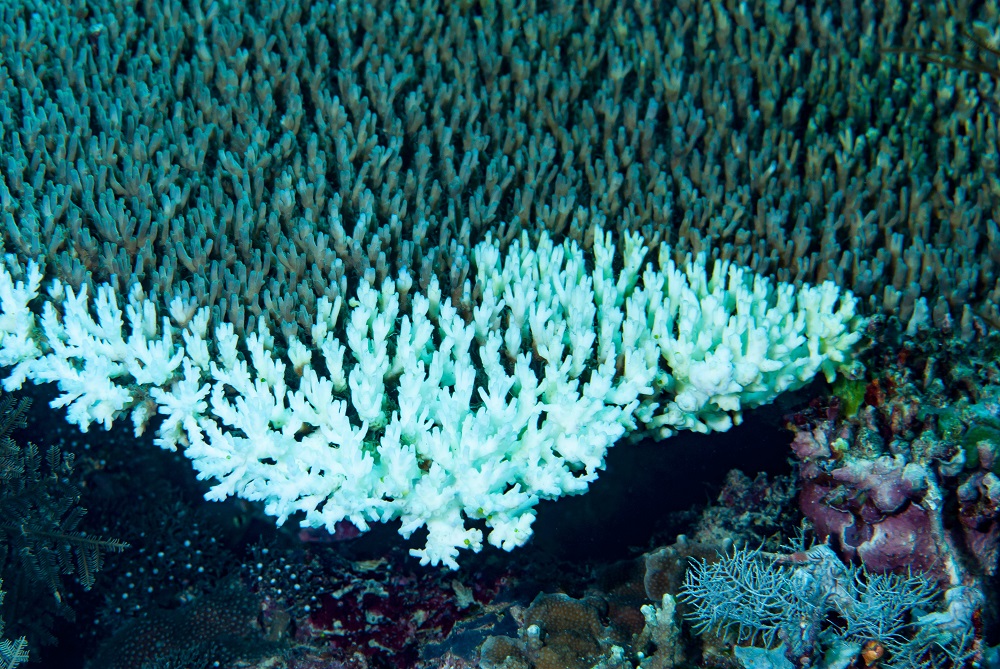

What is behind this recent momentum? Ocean biodiversity losses are so severe that even countries that benefit the most from unrestricted access to marine resources are finding reason to take action, argues Dr Ryabinin. “What is happening now is so bad that it has started to touch those who have it all. Even presidents understand they are doomed to experience the tragedy of the commons,” he argues. “The tragedy of the commons is getting close attention from everyone on climate, biodiversity and the ocean.”

Protecting the high seas

Until now, most of the ocean has been effectively ungoverned. Almost two-thirds lie outside the “exclusive economic zone” of any country (an area that stretches up to 200 nautical miles off the coastline). Unregulated and unmonitored, these “high seas” are vulnerable to exploitation by states and criminals. They are hotbeds for piracy, human trafficking and smuggling. Two-thirds of the fish stocks in these areas are overexploited while about only 1% have a protected status.

The High Seas Treaty aims to change that by establishing the legal framework to create marine protected areas (MPAs) in international waters. Countries that sign the final agreement can nominate areas for protection. Signatories will then vote on the plan; if three-quarters support it, a new MPA will be created, curbing activities such as fishing and shipping. The treaty also obliges countries to carry out environmental impact assessments for activities such as deep-sea mining. It promises to “fairly and equitably” share the profits from “marine genetic resources”: materials from ocean plants and animals that can be used in pharmaceuticals and cosmetics.

“The agreement is a step forward,” says Dr Ryabinin. Most important, he argues, is the way the High Seas Treaty works in tandem with the 30×30 target. If that goal is met, 30% of the ocean will be protected by 2030. “How we are going to organise ourselves in the remaining 70%—that is a big question,” he says.

The deal will enter into force after 60 countries have passed legislation to adopt it, a process that could take years. There are still questions about how its rules would be enforced. But “I think we are approaching a new page in our relationship with the ocean, which is based on science,” Dr Ryabinin says. [“This is surprising to me, that science is heard now.”] For years, populist politicians have poured scorn on scientists’ warnings about climate change and biodiversity loss, but he is hopeful that “this paradigm is part of the past.”

Advancing ocean research

Still, ocean research remains poorly funded, notes Dr Ryabinin. There is no international convention requiring countries to support ocean research. Despite its importance, the ocean receives on average less than 2% of national research budgets. “Many things in the ocean require observation and deep knowledge,” he says. “But the current investment in such things is absolutely minimal.”

By one estimate, the global ocean economy is worth some US$2.5trn annually. Yet “investment in ocean science is in the order of tens of billions of dollars, and the IOC budget is about US$5m-6m a year,” Dr Ryabinin points out. “Hopefully we’ll get an increase, but it demands US$6m or US$7m annually. Out of that, US$5m will go for salaries. So that leaves US$2m to coordinate 70% of the planet.” That is, he argues, “just totally ridiculous.”

As the IOC’s executive-secretary, Dr Ryabinin has overseen efforts to bolster ocean research. Multilateralism saw a good year when he took the helm in 2015, with countries signing the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the Paris Agreement on climate change, and the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction. “We capitalised on that, but in all those agreements there was no significant mention of ocean science at all,” he recalls.

The UN responded in 2017 by proclaiming a Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (2021-2030). This aims to bring together ocean experts from across the world to foster partnerships, training and research. “Now it is the largest undertaking in ocean science in history”, Dr Ryabinin says. More than US$1bn has been committed to the Ocean Decade across 200 different projects, covering everything from ocean modelling to ethics. “It’s going to continue until 2030, and I hope very much that it will be a strong motivator for ocean science,” he says.

From promises to action

Reflecting on his eight years in office, Dr Ryabinin argues that countries have become more aware of the threats facing the ocean. “There is now a totally different situation,” he argues. “We now speak about hope to save the ocean … We created [the] conditions for saving the ocean on the basis of science and engagement.”

The next challenge—that will face his successor—will be implementing new treaties. “The work hasn’t been completed. We need to move to sustainable ocean planning,” Dr Ryabinin warns. “The next stage will be about the design of sustainable ocean planning, and creating infrastructure in nations and internationally to implement it.”

There may be a need for more quantitative targets to safeguard the ocean, he argues. The High Seas Treaty supports the goal to protect 30% of the ocean. However, it could also set its own targets, akin to those of the Paris Agreement, Dr Ryabinin suggests. “The new High Seas Treaty is a set of rules … but it doesn’t set concrete objectives,” he explains. “As soon as it comes into force it must also set some quantitative objectives … That is helpful for covering the remaining 70% of the ocean in a more sustainable way.”

More help is needed for low-income countries, Dr Ryabinin says, noting that “the situation in developing countries is really dire.” Covid-19 battered small island states that are dependent on tourism. “Now they are supposed to be behaving in a green way. But it’s about survival … So we really need to help small and developing states,” he comments. To this end, the High Seas Treaty promises funding and technical support for developing nations.

On all sides, “more ethics is required” when it comes to managing the ocean, Dr Ryabinin says. But reflecting on his time leading the IOC, he is positive. “I have to say the ocean brings together wonderful people,” he argues. “It just happens that the beauty of the ocean attracts nicer people, and because of them good things are happening.”

THE SUSTAINABILITY PROJECT

WORLD OCEAN INITIATIVE

WE WOULD LOVE TO HEAR FROM YOU

We welcome your feedback and comments.

If you have an editorial or media related request, a member of the media team will get back to you.

Back to Blue is an initiative of Economist Impact and The Nippon Foundation

Back to Blue explores evidence-based approaches and solutions to the pressing issues faced by the ocean, to restoring ocean health and promoting sustainability. Sign up to our monthly Back to Blue newsletter to keep updated with the latest news, research and events from Back to Blue and Economist Impact.

The Economist Group is a global organisation and operates a strict privacy policy around the world.

Please see our privacy policy here.

THANK YOU

Thank you for your interest in Back to Blue, please feel free to explore our content.

CONTACT THE BACK TO BLUE TEAM

If you would like to co-design the Back to Blue roadmap or have feedback on content, events, editorial or media-related feedback, please fill out the form below. Thank you.

The Economist Group is a global organisation and operates a strict privacy policy around the world.

Please see our privacy policy here.

World Ocean Summit & Expo

2025

World Ocean Summit & Expo

2025 UNOC

UNOC Sewage and wastewater pollution 101

Sewage and wastewater pollution 101 Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution

Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC

Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC