Professor Steve Widdicombe

Director of science and deputy chief executive at Plymouth Marine Laboratory

Plymouth Marine Laboratory is a world-leading ocean research institute based in the UK, working at the cutting edge of marine science to solve global ocean health challenges. Professor Steve Widdicombe’s work there as the director of science and deputy chief executive encompasses a wide range of policy-relevant scientific research in marine ecology, climate change, biodiversity and ecosystem function.

What is your biggest concern when looking at ocean health as a whole?

We tend to focus on the risks to human health, such as pollution, plastics, pathogens, and diseases like cholera, and rightly so. However, we talk very little about the positive health benefits we derive from the ocean as the restorative, health-giving entity that it really is. A lot more research needs to go into quantifying that link between a healthy marine environment and human health. We talk about mental health, like the ‘blue gym’ concept, which is the idea that our mental well-being can be hugely boosted by being close to the ocean and engaging in ocean pursuits. But there are also intrinsic links that we’re just beginning to explore, such as how some of the processes and chemicals produced by the ocean can have a positive influence on our physical health. Not to mention that as a provider of livelihoods, the ocean can help pull people out of poverty. So I think this needs to be a bigger focus. It’s not just about stopping the bad things from happening, but giving the ocean a chance to do all the good things for us as well.

We need to better understand the more difficult-to-quantify benefits we gain from the ocean so that we can have a better conversation around the relative values of our actions. At the moment, it’s so heavily skewed towards the direct financial benefit we get from extraction. It’s a very exploitative relationship. In human relationships—take marriage for example—you don’t look at your partner as someone who’s just going to give you financial security. You look at them as the person who gives you spiritual and emotional support, and overall well-being. But we don’t think about the ocean like that. Our relationship is purely exploitative: what can the ocean do for us, what can we take from it? I think we need to fundamentally change that relationship. Instead it needs to be more ethical, responsible and equitable between us and the ocean.

Is ocean health declining faster than the timelines predicted by the scientific community, and are there some timelines that we understand better than others?

Scientists are always tentative, because we’re of the mindset that we’ve got to be absolutely categorically sure of the statements we make. In fact, we have a tendency as a community to underplay the speed and severity of things that are happening, so it would not surprise me if some of the more extreme predictions play out. The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) shows us the difficulty of making hard and fast predictions about the future. Modellers are not fortune tellers; they can only give you a set of likely scenarios based on our current understanding. But it’s never a sure thing, and portraying the level of uncertainty has often been a struggle. With something like the AMOC, I don’t think anybody is forecasting a massive collapse of that circulatory system—they’re talking about slowing and the implications that has on weather patterns. I don’t see any prediction that I would stake my house on, like saying by 2037 all coral reefs will be dead, but the direction of travel is indisputable.

What is the most important area of focus for researchers?

My research wish would be that we spend enough time really understanding the consequences of our actions in the ocean so that we can make better informed, evidence-based decisions. For example, a recent paper found that a lot of metals are now leaching out of offshore renewables, and I’m not saying for one minute that we need to stop moving forward with offshore renewables, but we do need to understand all the consequences so that we can make better decisions and go with the least harmful scenario. We need to focus our research towards better understanding the consequences of human activities in the ocean, with the ultimate aim of having the smallest possible footprint on the ocean while still delivering the health and well-being benefits that we need.

How would you characterise the current state of ocean science research, from the perspective of funding, collaboration and technology?

Collaboration has always been one of the major strengths of ocean science. When you’re at sea on a research expedition, you work as a team, with different scientists working to address pieces of a bigger story. This attitude is built into the community, and we see it in Ocean Decade initiatives like the Ocean Conference. There’s a real willingness to collaborate, integrate, and be a community. I think this community is also really proactive in addressing autonomy, AI and machine learning, because we work in very difficult places, and autonomy allows us to do more. Overall, it’s a very creative, innovative community.

Regarding funding, the investment in Sustainable Development Goal 14 is way below everything else. It’s always been a struggle getting funding, and looking at the current geopolitical situation, it’s going to get even more difficult. Some of the community’s ambition is hampered by a lack of resources. Weather forecasting, which is recognised as an activity for the international public good, is effectively funded by governments coming together to commit to delivering an observing system, but there’s no similar funding ambition for ocean health observation. At the moment, it’s left to the overstretched, under-resourced science community. This comes right back to our initial conversation around recognising the ocean’s value. We see how much fish we can get out of it, or how we can use it to transport goods around, but those metrics don’t reflect the ocean’s true value.

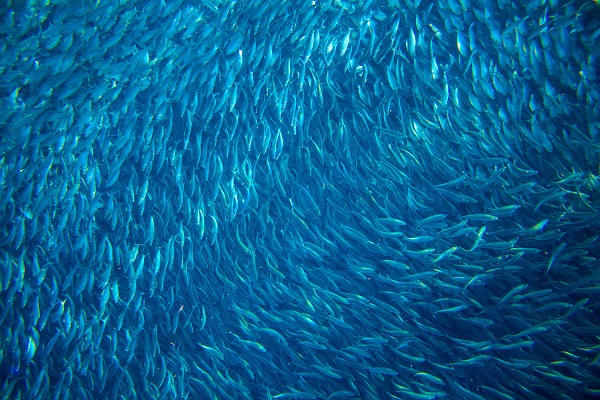

Another issue is the fact that the vast majority of the ocean sits outside anyone’s sole ownership. This could be a strength if we had a mechanism operating like the Antarctic Treaty, which protects Antarctica by saying it belongs to all of us, therefore it belongs to none of us. But we don’t have the same level of protection for the open ocean. Everyone’s staking their claims for mineral deposits, or massive factory ships are sucking up huge shoals of fish because it’s in no one’s territorial water, so it’s all fair game.

How worried are you about the impact of US politics on ocean science, given the US' role in the ocean science ecosystem until now?

The US’s role has been massive. They’ve been committed to major UN endeavours, like UNESCO and the International Atomic Energy Agency, which contributed to ocean science. But it’s not just the funding, it’s the thought leadership and capacity. US scientists have been bastions of delivering the required knowledge, and there is a lot to lose in terms of their performance and their independence—will we see a shift to policy-based evidence, where science is skewed towards supporting and justifying the government’s narrative? I’m very worried about how this will affect the globe’s capability to research and respond to some of the biggest environmental challenges the planet has ever faced. Similarly, what has happened to the Russian science community is very unfortunate; their datasets and knowledge have been effectively taken out of circulation. We would hope that science sits above geopolitical considerations, but in practice it doesn’t.

Last year started with a lot of optimism and ended with a lot of disappointment. The climate COP didn’t deliver the progress we were hoping for; the Convention for Biological Diversity COP didn’t get through all the work it needed to; and the plastics treaty negotiators didn’t rise to the challenge. In 2025 we need to finish the job that we should have finished in 2024.

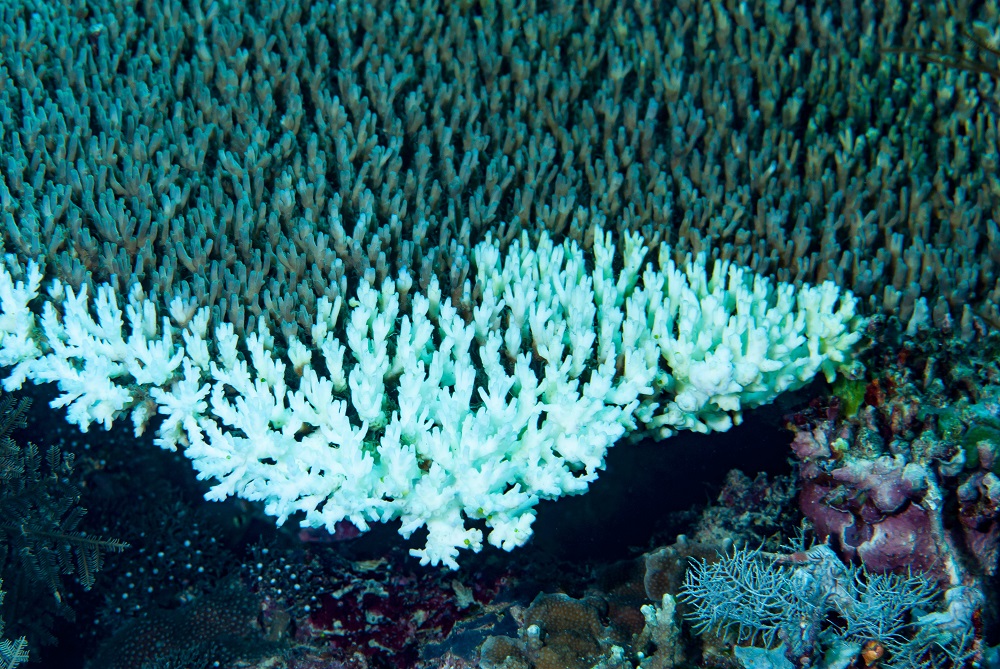

Finally, there's been interest in understanding the resilience of coral reefs and whether interventions can help. Do you think efforts to strengthen marine ecosystems’ resilience are a valid mitigation or adaptation strategy?

These interventions won’t fully compensate for the natural diversity that’s already been lost. Coral ecosystems are highly complex and have evolved over long periods, and artificial interventions can’t fully replace that biodiversity. Corals are very much adapted to the environment of their past. For example, corals in the Red Sea, which experience some of the highest ocean temperatures around the world, may have the potential to survive in other parts of the world that are warming up. But introducing species to new environments is risky, and we know from history that it has to be done cautiously to avoid unintended ecological consequences.

There are also groups trying to work with corals by identifying and supporting naturally resilient coral populations in their native regions and selectively cultivating corals that can better withstand higher temperatures. That’s a good thing, but it can’t completely prevent biodiversity loss. Ultimately, no outcome will be as good as limiting the damage of global warming in the first place.

EXPLORE MORE CONTENT ABOUT THE OCEAN

Back to Blue is an initiative of Economist Impact and The Nippon Foundation

Back to Blue explores evidence-based approaches and solutions to the pressing issues faced by the ocean, to restoring ocean health and promoting sustainability. Sign up to our monthly Back to Blue newsletter to keep updated with the latest news, research and events from Back to Blue and Economist Impact.

The Economist Group is a global organisation and operates a strict privacy policy around the world.

Please see our privacy policy here.

THANK YOU

Thank you for your interest in Back to Blue, please feel free to explore our content.

CONTACT THE BACK TO BLUE TEAM

If you would like to co-design the Back to Blue roadmap or have feedback on content, events, editorial or media-related feedback, please fill out the form below. Thank you.

The Economist Group is a global organisation and operates a strict privacy policy around the world.

Please see our privacy policy here.

World Ocean Summit & Expo

2025

World Ocean Summit & Expo

2025 UNOC

UNOC Sewage and wastewater pollution 101

Sewage and wastewater pollution 101 Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution

Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC

Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC