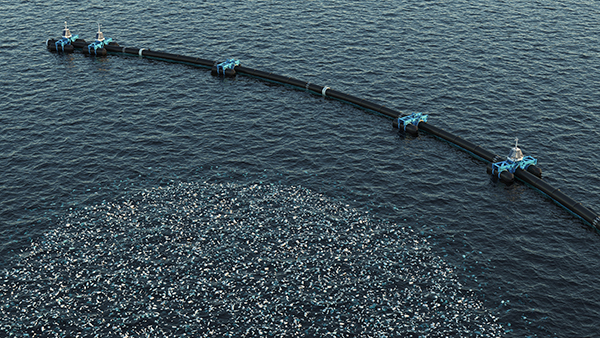

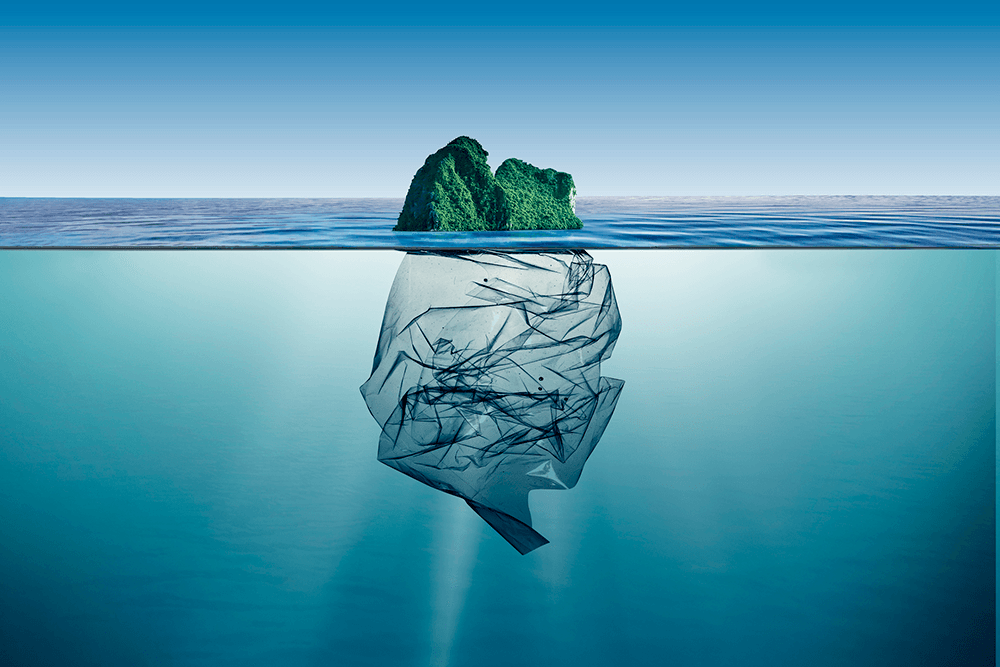

Plastic cluttering beaches and shorelines has become a common sight. However, what is lesser known is the fact that ocean pollution contributes to the estimated nine million premature deaths occurring due to pollution annually. Human activities leading to climate change and other environmental disruptions have caused sea temperatures to rise and glaciers to melt and disrupted the delicate balance between species within ecosystems. Foremost among our damaging activities is using plastics, with low rates of recycling and over-utilisation of single-use products leading to accumulation in oceans—and representing over 85% of all marine litter.

Over time, plastic debris is degraded by weathering, mechanical abrasion and sunlight, eventually broken down into microplastics—microscopic particles smaller than 5mm—which can now be found in deep-sea sediments of the far-flung Arctic and Antarctic. The lesser-known nano-plastics, less than 1 m in diameter, are also an issue. Microplastics also enter marine ecosystems as direct waste products as plastic beads used in industrial processes.

Microplastics, in the form of pellets, fibres and granules, are vectors for toxic substances, as they bind to and accumulate these agents before being ingested by marine organisms. They also contain large quantities of chemical additives incorporated during manufacture, including toxic chemicals such as phthalates, heavy metals, perfluorinated additives and synthetic dyes. These chemicals are all known for their deleterious effects, ranging from mutagenicity, carcinogenicity, endocrine disruption and impacts on reproductive health and fertility.

Although plastics are not harmful to humans in most everyday uses, the problems start when it becomes waste. To help grasp the severity of the problem, Jacqueline McGlade, professor of natural prosperity, sustainable development and knowledge systems at UCL explained the issue of lugworms to Back to Blue.

Describing them as the architects of sediment who work to oxygenate their environment and keep it healthy, the lugworms become sluggish and non-functioning when they mistake these particles as food. This, in turn, throws their entire ecosystem, which many other organisms rely on for food and livelihood, out of balance.

Even more sinister is the effect of microplastics on humans in a painful sequence of reciprocal cause and effect. With their global distribution in water and air, they are now found in seafood, exposing humans through ingestion of contaminated fish or shellfish, although inhalation of airborne microplastics may be an even greater source of exposure.

Ms McGlade describes the challenges facing human health, beginning with the waste’s generation. Microplastics used in fertilisers encapsulate the active components and allow for safe delivery. They eventually break apart and make their way into freshwater runoff, she explains. With wastewater treatment plants currently unable to and/or not required to extract micro- and nano-plastics, these and any other pieces of plastic found in wastewater flowing into oceans become part of the problem.

Another source is the wear and tear of automobile tires, creating aerosolised plastics that pollute the air, or maritime accidents leading to spills or lost cargo, with commonplace items like discarded cigarette butts and personal hygiene products contributing too. Dr Subhankar Chatterjee, assistant professor in the Bioremediation and Metabolomics Research Group at the Department of Environmental Sciences at the Central University of Himachal Radesh in India, adds sources such as intravenous tubing and bags for collecting and storing plasma, which all eventually make their way into the ocean. He has been working in this field for almost 20 years and thinks there is a need to change attitudes towards plastics use. He cites examples of those in the developed world preferring to use bottled water and not reusing or recycling, or supermarkets wrapping fruit in plastic.

The physical effects of excessive plastic waste can be seen where they accumulate in large volumes, deterring people from going to the beach, Ms McGlade asserts. Beyond these physical scourges is the significantly larger chemical effect of microplastic pollution on human health. As Ms McGlade remarks, “we know that chemicals [that are] used in the manufacturing of plastics and many other contaminants that come in via freshwater into the ocean are substances of concern. We know what their direct effect is on human health; some bioaccumulate in organs, some even cross the placental border and can be found in all of the neural tissues, and there’s just one long and unpleasant list of health conditions that these trigger.”

But we cannot observe a direct relationship between our health and exposure to plastics in the water, Ms McGlade argues. The effect on human health arises via the food chain, an observation that Dr Chatterjee firmly agrees with. “Once it is in the food chain, then it will be in the human body”, he outlines bluntly, touching also on what this means for those who live near the sea and consume lots of seafood. The bioaccumulation of microplastics in the fish, which are then eaten by humans, can lead to issues such as endocrine disruption, infiltrating the signalling between hormones and their receptors and preventing important processes from taking place.

Since 2016 a new area of research has emerged, relating to plastic waste in the environment. The Plastisphere, a community of microorganisms growing as a thin layer around plastic, is analogous to the layer of life outside Earth called the biosphere. Ms McGlade describes it as a rafting mechanism, where plastic provides a platform and creates a new habitat comprised of microbial populations not typically found in sizeable concentrations in the ocean. This allows certain organisms to accumulate to higher degrees, including pathogens such as Vibrio cholerae, the pathogenic bacterium causing cholera, which would not normally be found in the sea.

Coral reefs are also affected, indirectly affecting human health. Dr Chatterjee explained to Back to Blue the mechanism behind this: coral reefs receive nourishment from various sources, including phytoplankton, zooplankton and other small organisms in the sea, which ingest and bioaccumulate microplastics. This in turn affects the coral when they feed on these organisms, with the plastics accumulating in their gut cavity and ultimately damaging their health.

Ms McGlade outlines a similar tale of woe for coral reefs affected by microplastics. Pollution has a direct impact on the fertility, productivity and resilience of coral reefs, she says, leading to their death and depletion. This subsequently opens up coastal areas to destruction by storms. As humans rely on coastal systems for protection, affected corals have an indirect effect on human health and wellbeing.

What about other sources of marine pollution? Ms McGlade lists some examples: oil spills continue to plague our oceans, while mining and coal production send aerosolised mercury emissions into the ocean, the effects of which are well documented and include devastating effects on pregnancy, lactation and anyone exposed to mercury via the food chain. Harmful algal blooms can produce cyanide, which is harmful to the neurological and cardiac systems.

Both experts painted a grim picture of marine pollution, particularly microplastics, but there is some optimism. Alternatives to conventional plastics are viable. Ms McGlade points to interesting research out of Cairo, which involved the production of plastic made from prawn shells, for example. Dr Chatterjee spoke of a general move away from single-use plastics and some countries leading the way with plastic-free initiatives, although he hopes the fast-moving consumer goods sector would begin to do their bit.

But given the scale of the plastics pollution crisis, and the mounting evidence of its impact on marine and human health, far more action will be needed to improve how we manage our plastics – and greater innovations required to find alternative materials in the future.

Read more on the Plastic Management Index which examines plastic management through the lens of policy, regulation, business practice and consumer actions at a country level.

THANK YOU

Thank you for your interest in Back to Blue, please feel free to explore our content.

CONTACT THE BACK TO BLUE TEAM

If you would like to co-design the Back to Blue roadmap or have feedback on content, events, editorial or media-related feedback, please fill out the form below. Thank you.