Destination unknown

Reading time: 4mins

A tidal wave of new initiatives masks a worrying lack of progress on tackling plastic pollution

CONTENT FROM

The ocean is drowning in plastic: 11 million tonnes enter the seas each year. Without dramatic action, this could reach 29 million tonnes annually within the next two decades.

Not long ago, plastic pollution was a hidden problem. No more: a tsunami of policies, research projects and awareness-raising activities has swept over the business and policy communities. The Circulate Initiative identified more than two dozen new initiatives released in the first half of 2020 alone.

Yet this tidal wave of good intentions has not translated into substantive and meaningful action. We are still drowning in plastic.

Partly this is because tackling plastic pollution requires long-term solutions. Many new initiatives have emerged in the past three years; most are yet to report their progress. Others are still emerging.

But, worryingly, our conversations with scientists, analysts and activists suggest that, despite the flurry of activity, critical gaps mean that progress on tackling plastic pollution may yet be stymied.

Legislation is lacking

Research by a team at Duke University, published in mid-2020, shows that government programmes and policies to tackle plastic pollution are often piecemeal. Policymakers are now aware of plastic waste, and many are acting on that awareness, yet few countries have introduced comprehensive national plans. Most legislative instruments are plastic bag bans or taxes or focus on a specific type of plastic pollution.

Seven of the top 20 coastal countries producing mismanaged waste from land-based sources do not have any national-level policy. Another four only ban plastic bags. We now know that much of the plastic waste in the ocean gets there via rivers. Yet the Duke research found that four of the world’s most polluted rivers (the Amazon, the Irrawaddy, the Mekong and the Pasig) flow within countries with no national policy on plastic pollution.

Time for a progress report

Commitments are rife, but few governments and companies report on their progress towards meeting them (not publicly at least). No initiative has emerged to track or monitor these pledges. ‘Blue-washing’ may be endemic: we don’t know.

This lack of evaluation extends to the growing body of academic research, too. The Circulate Initiative study found that while a substantial number of resources explain the problem or identify solutions, relatively few evaluate progress or assure results. Duke University’s research similarly found that while some studies assess plastic bag bans’ effectiveness, very few assess the efficacy of other policy interventions. None evaluate policies designed to tackle microplastics, for example. Legislation aimed at reducing plastic pollution may be working, or it may not. Again, we don’t know.

Too much information

So many overlapping initiatives make redundancy a real risk. Decision-makers cannot absorb all the information; governments struggle to make sense of the wide range of policy recommendations.

Several researchers privately admit that translating complex scientific research about plastic waste into language policymakers and understanding remains challenging. Often, they can engage successfully with environment ministries but struggle to reach regulatory authorities and fiscal policymakers that can effect real change.

Primary data, metrics and definitions are often still lacking. Many countries measure mismanaged waste but not how much flows into the ocean, for example, leaving researchers to rely on estimates and assumptions to fill the gaps.

Standards and certifications for recycled and reclaimed plastic are messy and can be easily misused. Companies can claim to use recycled or ocean plastic in their products, but there are no agreed definitions of what this means. Businesses bluewash knowing their claims are difficult to verify.

Swimming upstream

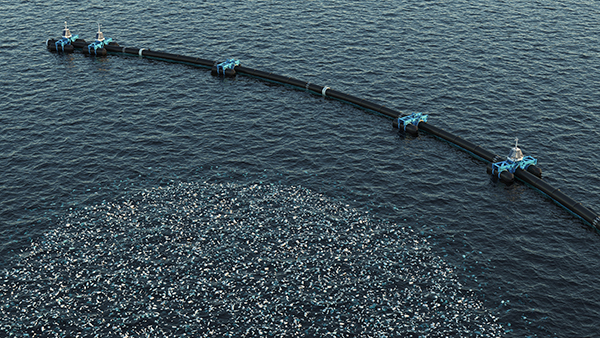

Reducing plastic use is likely to be the most impactful and cost-effective way to stem the tide of plastic waste, according to Breaking the Plastic Wave, a 2020 analysis published by The Pew Charitable Trusts and SYSTEMIQ. Yet most initiatives focus on downstream solutions such as improved waste collection and plastic recycling. Upstream solutions such as plastic alternatives or improved packaging offer significant economic opportunities, yet initiatives to finance this type of innovation are rare.

Time to turn good intentions into results

A decade ago, plastic pollution barely rated in the public consciousness. Our survey data show that both the business community and the general public now rank it as the top priority for restoring ocean health. That so many scientists, policymakers, non-government organisations and sections of the business community are working to address this issue suggests that we can expect to see progress. But the job is far from done. We should not mistake activity for results.

Think about the degradation of the ocean. What should be the top priorities for restoring ocean health over the next five years?

Back to Blue global survey conducted in Jan 2021

The Back to Blue Plastic Management Index will be released in September 2021. Jessica Brown is head of engagement for the Back to Blue Initiative.

Plastics Management

The future of the ocean:

Part Two

Reading time: 8mins

The future of the ocean:

The tech to tackle plastics

Reading time: 8mins

Peak plastics: bending the consumption curve

Reading time: 10mins

Plastics Management Index Whitepaper

Reading time: 16mins

Businesses and consumers' attitudes to plastics use and management

Reading time: 5mins

ENVISIONING CIRCULARITY: SOUTH-EAST ASIA’S PLASTICS MANAGEMENT CHALLENGE

Reading time: 2mins

FROM INTENTION TO ACTION: INDIA’S PLASTICS MANAGEMENT CHALLENGE

Reading time: 2mins

THE STRUGGLE FOR CIRCULARITY: GHANA EMBRACES ITS PLASTIC WASTE CHALLENGE

Reading time: 2mins

videos

THANK YOU

Thank you for your interest in Back to Blue, please feel free to explore our content.

CONTACT THE BACK TO BLUE TEAM

If you would like to co-design the Back to Blue roadmap or have feedback on content, events, editorial or media-related feedback, please fill out the form below. Thank you.

Back to Blue is an initiative of Economist Impact and The Nippon Foundation, two organisations that share a common understanding of the need to improve evidence-based approaches and solutions to the pressing issues faced by the ocean, and to restoring ocean health and promoting sustainability