The Invisible Wave

Think you can live without man-made chemicals? Think again. According to the International Council of Chemical Associations, 95% of all manufactured goods rely on chemical ingredients or processes. Every time an object is made without chemicals, another 99 are made with chemicals.

In many ways, this is good news. Since the industrial revolution, the chemical industry has been an incredible driver of prosperity and productivity. Yet the sector has not yet begun to reckon with the potentially devastating effects of toxic or mismanaged chemicals on the environment.

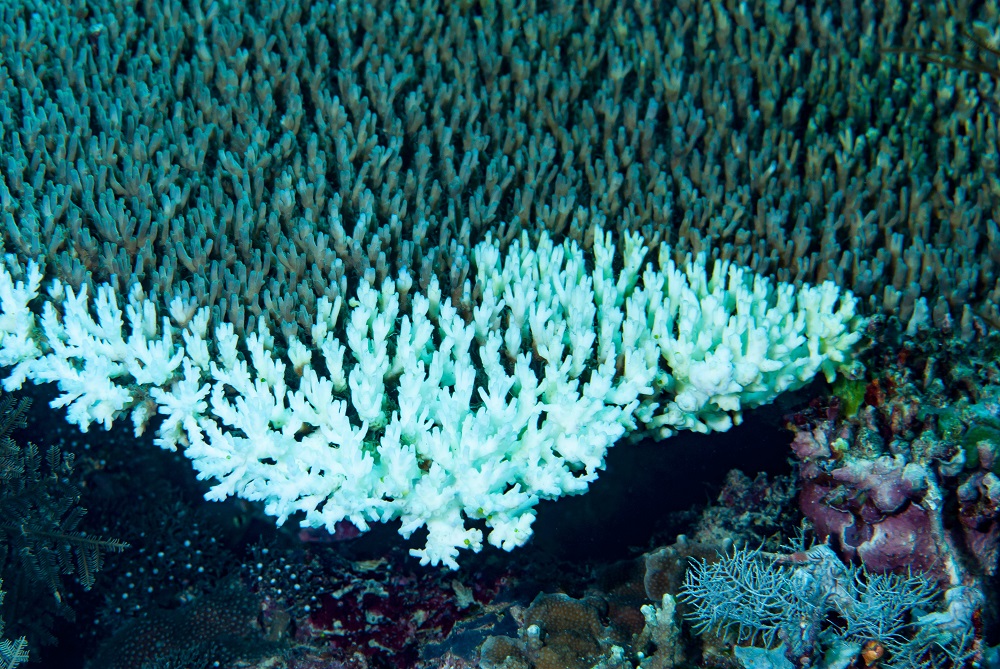

The chemicals sector is the third-largest carbon heavy industry in the world, accounting for 18% of industrial emissions. And, as Back to Blue’s research has found, chemical pollution in the ocean is a profoundly urgent and vastly underappreciated problem that, if left unchecked, will be disastrous for marine ecosystems and human health.

Governments and businesses alike must do more to stop chemical waste from entering the ocean. Technology already exists to improve sewage and stormwater systems, upgrade industrial waste treatment processes and stop agricultural runoff from entering the seas—but cost is the barrier.

Yet better waste management alone won’t stop chemicals from entering the ocean. Products from sunscreens to flame retardants to pharmaceuticals that inevitably find their way into the seas will need to be redesigned to reduce or eliminate chemicals that harm the marine environment.

This means that the chemicals sector has a vital role to play in addressing marine pollution.

Fortunately, there is some good news. Parts of the industry are beginning to transition their product portfolios to become less toxic and less polluting. European chemical companies are leading the way, spurred on by the world’s tightest regulations. Others, such as Thai company Indorama Ventures, have voluntarily adopted more sustainable practices to attract investors who value companies with strong environmental records.

The burgeoning green chemistry sector is another bright spot. Start-ups and incumbents alike are competing to design non-toxic solvents, safe biofuels and dissolvable plastics that could in time replace many of the chemical products we currently use—and will be critical in the transition to a circular economy.

Big-brand retailers such as Apple, Nike and Ikea are providing impetus for the chemical sector to transform, too, demanding that suppliers stop using harmful and toxic chemical substances.

Yet substantial challenges remain. Patchy regulation and enforcement mean that chemical companies pollute without penalty in many parts of the world. Poor labelling and complex supply chains mean consumers are often unaware that there are harmful chemicals in the products they buy. Some of the most polluting firms are well-funded, well-organised political lobbyists.

Even those firms that want to change must jump substantial hurdles. Chemical companies, particularly those that produce the fossil-fuel-based commodity chemicals such as ethanol and ammonia that make up a large chunk of the industry’s revenue, operate in a ruthlessly competitive and low-margin commercial environment. To turn a profit, they must operate at an enormous scale.

This means that changing products and processes is a capital and time-intensive process that can cost billions of dollars and take decades. Replacing polluting chemicals can mean recalibrating complex global supply chains. It’s not realistic to expect chemical companies to do this alone, and it’s wishful thinking that their shareholders would support it.

Marine chemical pollution is a systemic problem that can only be addressed by systems-level solutions. Governments, the chemical industry, retailers, investors and scientists will need to work together to find ways to transform the sector from being a source of marine pollution to a source of innovative solutions to pollution. Nothing short of a green (or blue?) chemical revolution is needed.

Back to Blue is an initiative of Economist Impact and The Nippon Foundation

Back to Blue explores evidence-based approaches and solutions to the pressing issues faced by the ocean, to restoring ocean health and promoting sustainability. Sign up to our monthly Back to Blue newsletter to keep updated with the latest news, research and events from Back to Blue and Economist Impact.

The Economist Group is a global organisation and operates a strict privacy policy around the world.

Please see our privacy policy here.

THANK YOU

Thank you for your interest in Back to Blue, please feel free to explore our content.

CONTACT THE BACK TO BLUE TEAM

If you would like to co-design the Back to Blue roadmap or have feedback on content, events, editorial or media-related feedback, please fill out the form below. Thank you.

The Economist Group is a global organisation and operates a strict privacy policy around the world.

Please see our privacy policy here.

World Ocean Summit & Expo

2025

World Ocean Summit & Expo

2025 UNOC

UNOC Sewage and wastewater pollution 101

Sewage and wastewater pollution 101 Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution

Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC

Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC