At Back to Blue, we think a lot about man-made chemicals. So much so that we’ve spoken with more than 100 experts from government, business, non-government organisations and the scientific community to learn more about ocean chemical pollution and how to fix it.

Their responses have been eye-opening. Scientists told us a similar story: marine chemical pollution is an urgent crisis that must be addressed immediately to avoid irreversible ecological damage.

Business and government leaders, however, responded quite differently (if they agreed to talk to us at all). Marine chemical pollution, most said, is not on their radar. They are not necessarily obfuscating (although some, no doubt, are). It’s just that with a focus on plastic pollution and decarbonisation, they haven’t begun to consider other types of marine pollution yet.

The first step to addressing marine chemical pollution must be to close this perception gap between scientists and decision-makers.

The next step is to address the data gap. The scientists we interviewed acknowledged that our collective knowledge of marine chemical pollution is patchy and incomplete. Yet a lack of data, they told us, shouldn’t be a barrier to action: we know enough about the problem to know we must act.

For decision-makers in government and business, this is not enough. Data must be compelling enough to base regulatory and financial decisions on. Money talks, but we don’t know enough about the extent and effect of marine chemical pollution to correctly estimate the economic cost to ecosystem services and human health. This makes it difficult for regulators and executives to act: how can they effectively compare the price of inaction with the cost of various solutions?

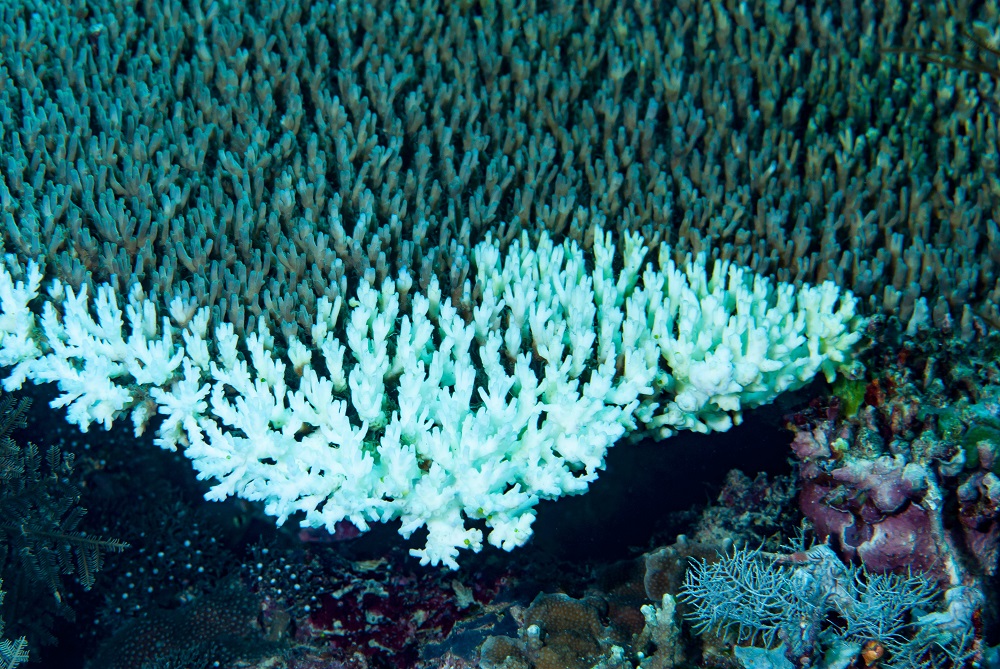

Our study, The Invisible Wave, examined the economic cost of eutrophication, or dead zones, in the Gulf of Mexico. Dead zones occur when chemical fertilisers used in agriculture run into the ocean. Excess nutrients cause algae to grow out of control, creating pockets of low oxygen—harming fish and other marine life.

Our modelling found that the US could lose US$838m in fisheries revenue annually should dead zones worsen in the Gulf.

This is one small case study in an area that is relatively well studied. Extrapolate this figure to the entire ocean, and it is easy to see how devastating the economic cost of marine chemical pollution could be.

At Back to Blue, our message is clear: there is more to marine pollution than plastic.

The recent UN Ocean Conference in Lisbon has helped to galvanise momentum towards solving the plastic pollution crisis. Yet pollution in the broader sense—chemicals, agricultural runoff and urban wastewater—barely rated a mention.

Our goal: putting marine pollution, not just plastic, front and centre at the next UN Ocean Conference in five years’ time. We need to make the invisible visible.

Back to Blue is an initiative of Economist Impact and The Nippon Foundation

Back to Blue explores evidence-based approaches and solutions to the pressing issues faced by the ocean, to restoring ocean health and promoting sustainability. Sign up to our monthly Back to Blue newsletter to keep updated with the latest news, research and events from Back to Blue and Economist Impact.

The Economist Group is a global organisation and operates a strict privacy policy around the world.

Please see our privacy policy here.

THANK YOU

Thank you for your interest in Back to Blue, please feel free to explore our content.

CONTACT THE BACK TO BLUE TEAM

If you would like to co-design the Back to Blue roadmap or have feedback on content, events, editorial or media-related feedback, please fill out the form below. Thank you.

The Economist Group is a global organisation and operates a strict privacy policy around the world.

Please see our privacy policy here.

World Ocean Summit & Expo

2025

World Ocean Summit & Expo

2025 UNOC

UNOC Sewage and wastewater pollution 101

Sewage and wastewater pollution 101 Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution

Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC

Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC