Ocean assessments, for instance, provide detailed scientific analyses of different aspects of marine life, and such studies date back over a century, but “there is no cohesive concentration of knowledge that is synthesised in a way that is useful, actionable and implementable at a local level,” says Ms Brodie Rudolph. The World Ocean Assessment is an impressive, detailed record of the state of ocean health but it lacks forward-looking scenarios that, according to Ms Brodie Rudolph, are an important stimulus for policy decision-making.

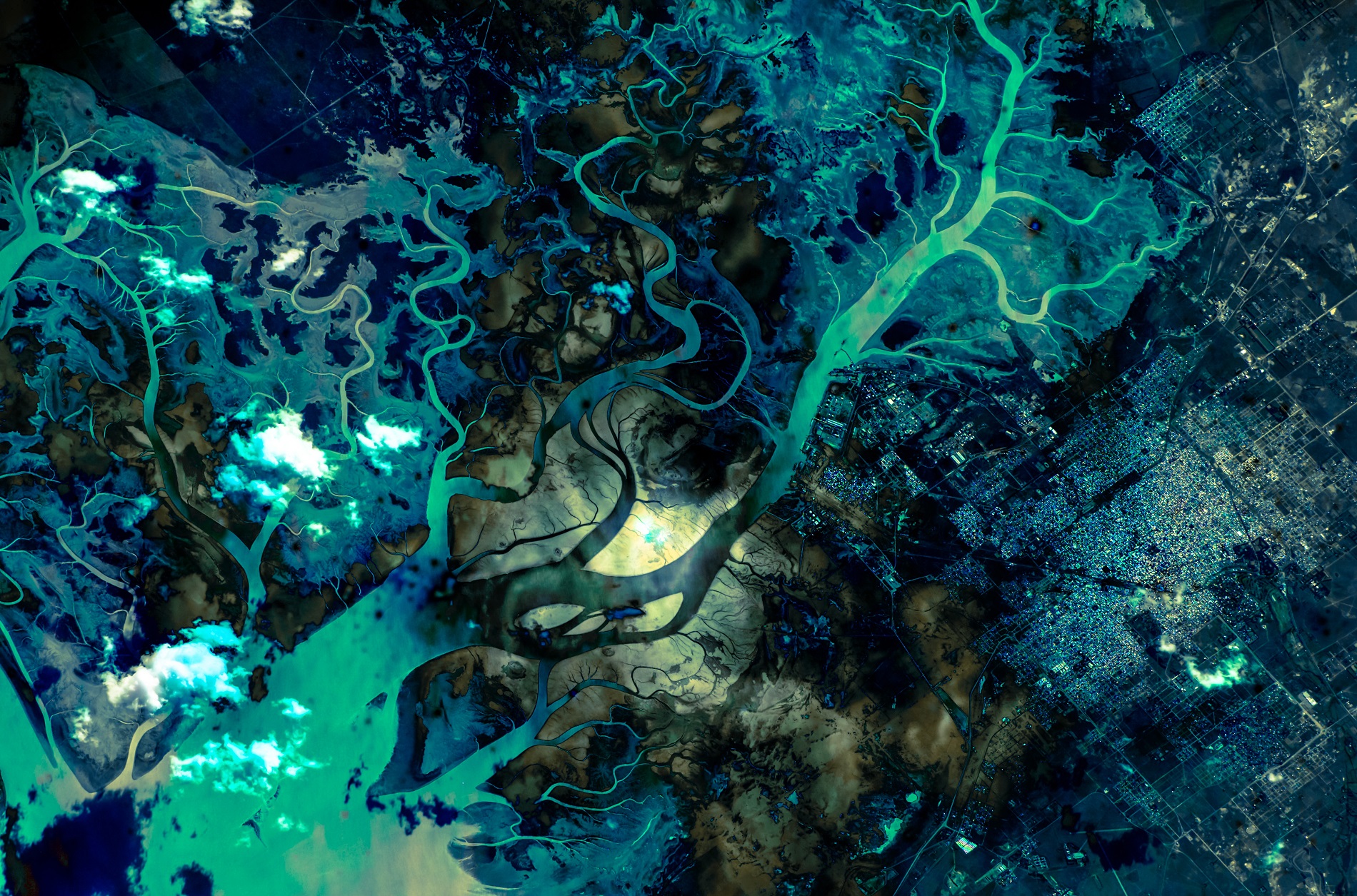

The IPCC includes ocean assessment and recognises the ocean’s role in regulating the climate as a carbon sink, but the focus of these reports is climate. The IPBES, meanwhile, offers useful scenarios and forward-looking analysis, Ms Brodie Rudolph says, but approaches the ocean from a biome perspective. This simply mean an area that is classified according to the species that live in it. “The ocean is part of the earth system. It is an integral part of the air we breathe, the food we eat, and the weather we experience, so a biome perspective is limiting.” The International Resources Panel published a report on coastal resources, which looks at coastal and land governance and the overlap that occurs on the coast in areas where land and ocean uses intersect, but governance of combined impacts is approached through separate laws.

“Those two need to be integrated to have an idea of the impacts we are having,” says Ms Brodie Rudolph. She adds that an issue like eutrophication, characterised by excessive plant and algal growth due to increased availability of inputs like carbon dioxide or nutrient fertiliser, is governed by specific instruments, but there are multiple impact pathways such as eutrophication from farming, tourism development, overfishing and agriculture farms. “Each of those parts are governed by different instruments. We need to understand how these things intersect.”

The scourge of untreated wastewater

The scourge of untreated wastewater Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution

Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC

Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC