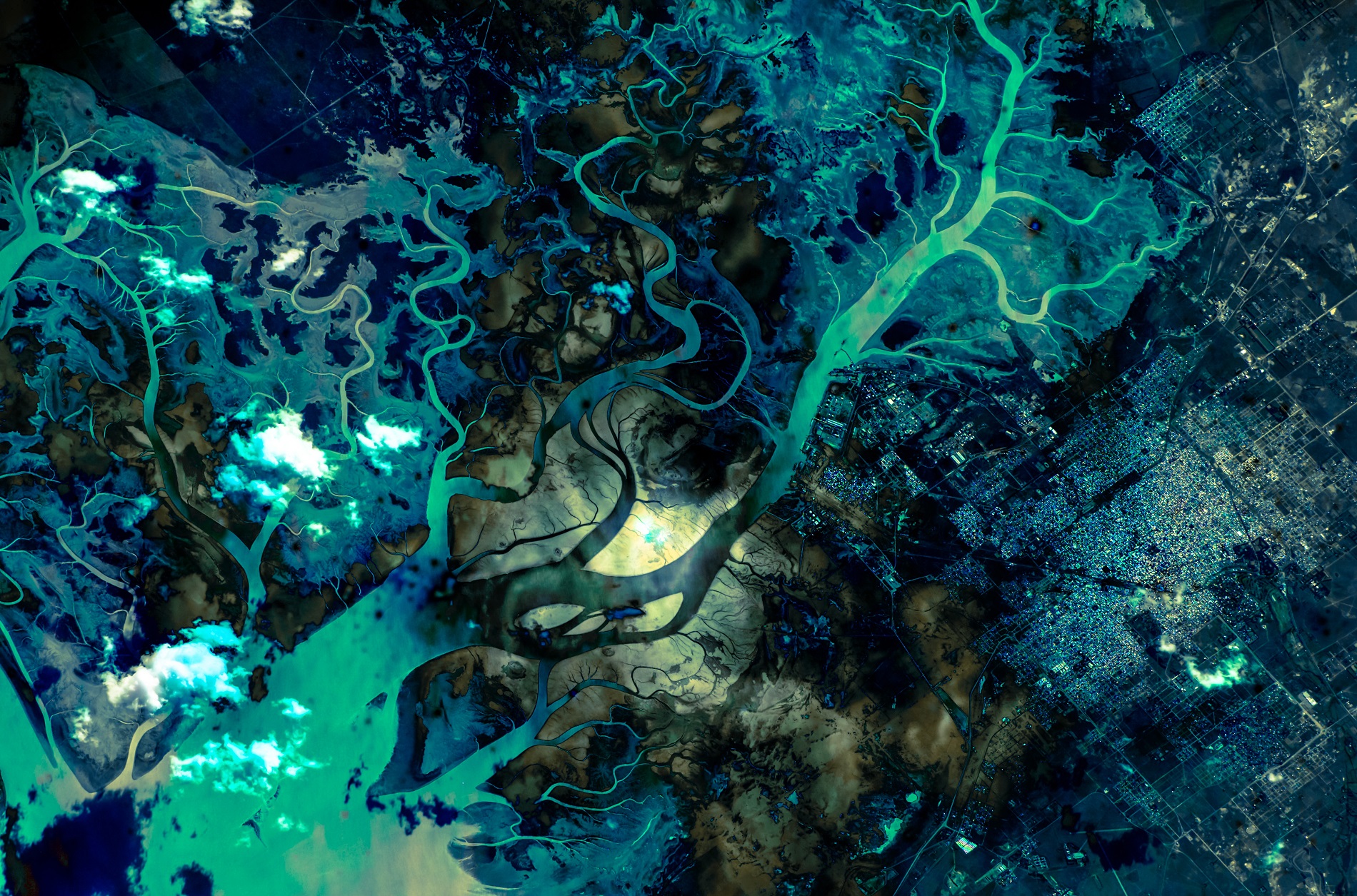

As Drucker predicted, scientists’ inability to measure the scale of marine chemical pollution has translated into poor management by governments. A fragmented patchwork of international, national and sub-national regulations exists but has not effectively addressed the growing problem.

Solutions exist, but implementing them will be politically difficult and expensive. In the European Union, the REACH legislation – which stands for ‘Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals,’ puts the burden of proof on companies to demonstrate that their products are not harmful.

Yet this precautionary approach is the exception, not the rule. In many countries, the opposite is true: the onus is on policymakers to prove that a product is harmful. Rapid technological innovation in the chemicals sector means governments simply can’t keep up – particularly in low-income countries with limited technical capacity and resources.

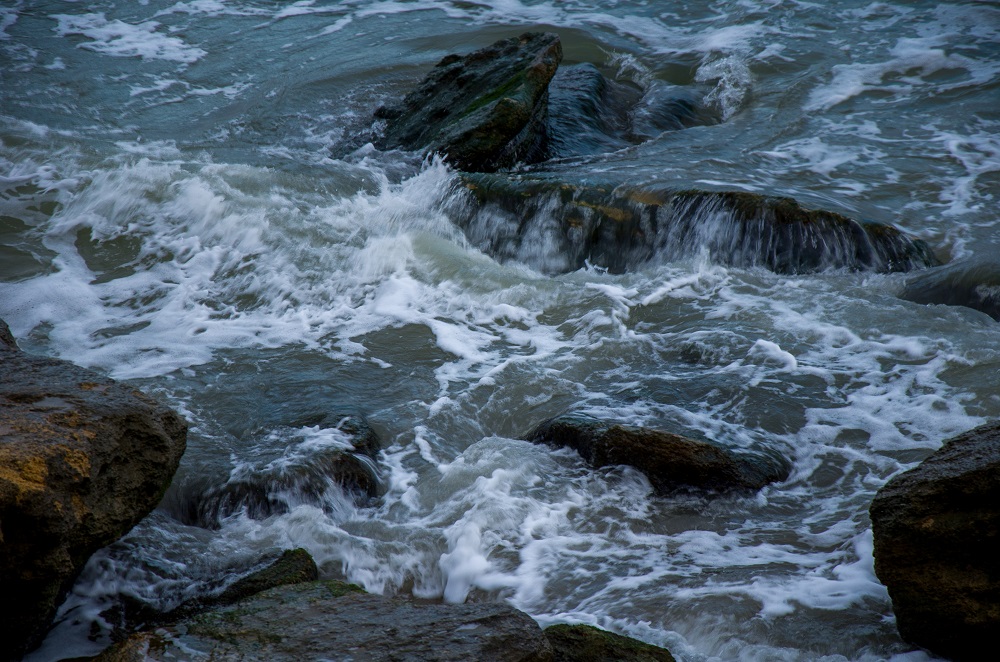

The scourge of untreated wastewater

The scourge of untreated wastewater Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution

Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC

Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC