These are traditionally considered the most dangerous and gain the most media prominence. However, another often overlooked scale is low-level exposure to novel and potentially toxic substances, which accumulate in wildlife and in human bloodstreams. Even small amounts of some of these persistent chemicals are implicated in various chronic health disorders. The often-undetected buildup of these contaminants in our bodies and environment, with potentially dangerous consequences, is an insidious form of pollution. “We don’t know how big the problem is, and we don’t know the full range of chemicals,” said Mr Damania. “If you’re going to try to solve the problem, you have to know how big the problem is.”

Essential first steps include ramping up monitoring and scientific research to identify key harmful chemicals and then switching to less toxic alternatives where possible. Consistent global monitoring programmes are needed to track different classes of chemicals. However, these currently lack sufficient support. The panellists emphasised the importance of deploying the precautionary principle to ramp up the scientific response to chemical pollution. Climate change is a huge source of uncertainty, making the potential impacts of pollution even more unclear as higher ocean temperatures may cause unprecedented chemical reactions. “There is still scientific uncertainty about the impact of chemicals, and we need to manage that risk amid the uncertainty,” said Yukari Takamura, professor at the University of Tokyo’s Institute for Future Initiatives. “That is one of the pillars of environmental policy.”

Amid this uncertainty, chemical pollution must be addressed with a risk management framework. “A good start is to focus on the most harmful chemicals, those that we know cause cancer, and get them out of our products,” said Ms Hok. In the short term, swapping out the most harmful chemicals for safer options would be hugely beneficial. But over the long term, the broader challenge is to rethink how we design, manufacture and regulate chemicals used in large volumes. Scientists, engineers and educators must collaborate to foster innovation in materials and processes that avoid persistent, bioaccumulative and toxic chemicals from the start.

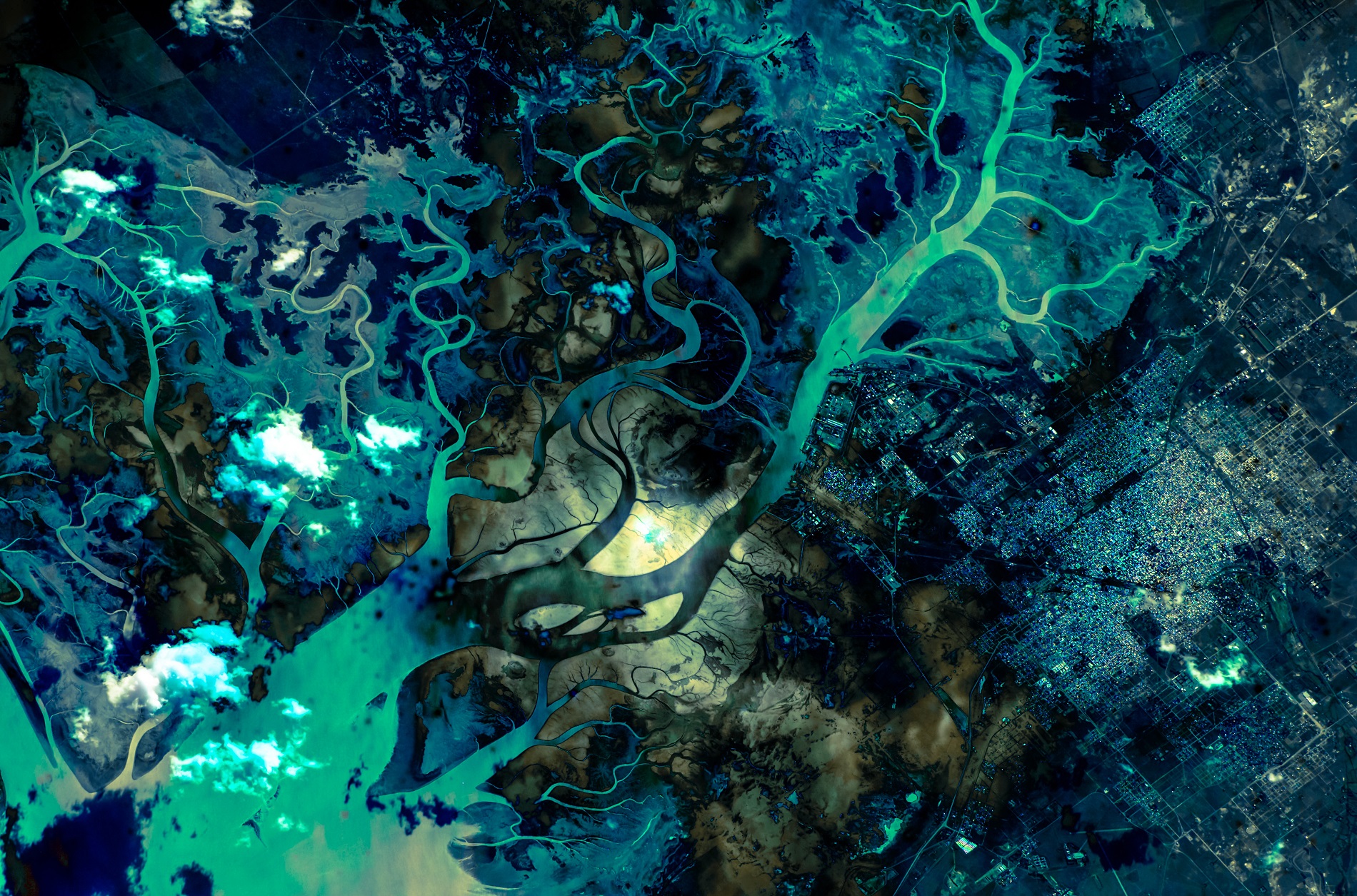

The scourge of untreated wastewater

The scourge of untreated wastewater Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution

Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC

Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC