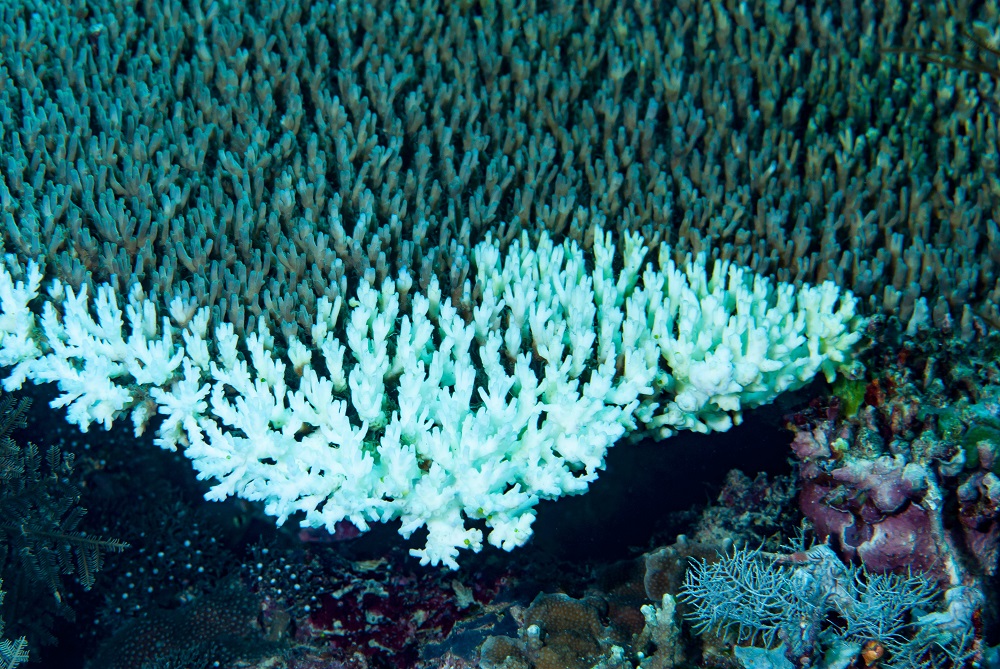

A toxic soup of chemicals is leaching into our oceans from a dizzying array of sources, ranging from agricultural pesticide runoff to electronic waste. Modern life is built on chemistry, with over 350,000 chemicals and chemical mixtures registered for production and use, according to a comprehensive 2020 study. This was more than double previous estimate, with 120,000 chemicals having been previously unknown, as their developers kept their details under.

The most worrying chemicals are persistent organic pollutants—the ‘forever’ chemicals that have been linked to adverse reproductive, developmental, behavioural, endocrine and immunologic health effects. Heavy metals like mercury and lead are another class of problem chemical, with established health risks, along with pesticides and plastics.

These work their way into the oceans from point sources, like the discharge of effluent from facilities; through atmospheric deposition, such as CO2 and nitrogen oxide emissions from petrochemicals used to manufacture plastics, thereby driving ocean acidification) and as run-off from land such as contaminated groundwater.

Source: ScienceDirect

The science of how different chemicals impact human health is evolving. According to a World Health Organization (WHO) calculation, a selection of chemicals, including lead, pesticides and occupational carcinogens, contributed to 2 million premature deaths and 54 million disability-adjusted life years in 2019, with lead alone responsible for nearly half of those deaths. Those figures were significantly higher than in 2016, when the premature deaths estimate was 1.6 million.

Companies are starting to confront the problem, which spans sectors ranging from fashion to consumer gadgets. Fashion retailer H&M and consumer goods giant Unilever have published 2030 roadmaps to strip out toxic and fossil fuel-based chemicals, respectively, from their supply chains, for instance. DSM, a Dutch multinational, has combed through its entire portfolio to pinpoint a range of ‘concerning substances’, including carcinogens and chemicals that disrupt the endocrine system.

International codes and charters are helping to galvanise governments and industry. The Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants is a global treaty to protect human health and the environment from this class of chemicals. Coalitions of companies between sectors are forming, like Roadmap to Zero, an alliance between chemical companies and retailers in the textiles and footwear sector, to reduce the industry’s chemical footprint. Meanwhile, the Responsible Care Charter is a chemicals industry code to promote safe management. The chemicals industry is the second-largest manufacturing sector and is growing fast; production doubled to 2.3 billion tonnes a year between 2000 and 2017, and will double again by 2030. This combines with a shift in location towards China and the Middle East, and among state-owned enterprises (SOEs), which limits the impact of Western-centric industry regulations and, in the case of SOEs, the relevance of otherwise important tools like sustainability-related financial disclosures.

Investors and shareholders are making meaningful demands on public companies to clean up their environmental profile as a whole—and consumers are increasingly agitating for companies and governments to do more to deal with the ecological crisis. History shows that, with industry focus, technological innovation and public pressure, environmentally risky industries can radically improve their performance—witness, for instance, the reduction in oil spills in recent decades.

But as with so many challenges in the climate crisis, voluntary pledges and announcements, and non-binding codes of conduct, are not enough. First, chemical supply chains are long and winding, and only as safe as their weakest link. Without global co-ordination, there is a risk of a race to the least regulated markets or simply a lack of transparency over how well chemical waste is managed along the supply chain. Second, consumer awareness of the chemicals crisis is still limited. Consumers themselves are part of the problem, such as through frequent disposal of harmful chemical products into the sanitation or waste system like pharmaceuticals or electronics.

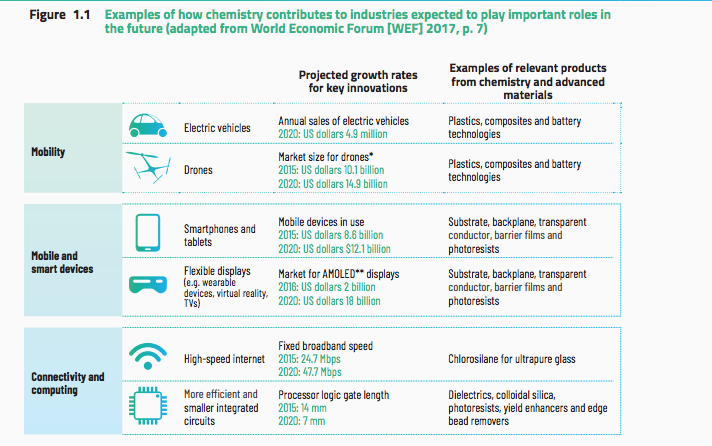

As with clean energy, transition depends on the availability of viable alternatives that are not just cost-competitive but can also be integrated into existing machinery and capital. Bold steps are needed to discover and make available less harmful chemicals. Attention is turning to ‘green chemistry’ as companies, start-ups and governments hope innovation will solve the problems we are facing today. BASF, a German conglomerate, has set itself a target of selling €22bn of so-called accelerators—solutions that it believes will make a significant sustainability contribution to the supply chain—by 2025. US plastics giant Dow Chemical is working with a range of start-ups in innovation hubs around the world to find better approaches to plastics management. Apple’s listing of ‘smarter chemistry’ as one of its three environmental priorities shows that the world’s most innovative brands are prioritising this problem. Unlike fossil fuels, a sunset industry that has no long-term future in a sustainable world, chemistry is also at the heart of many of the innovation vistas of tomorrow, from electric vehicles and drones to next-generation connectivity (see chart).

These could intersect with and support the needs of chemical-heavy industries. Precision agriculture, for instance, relies on technologies like drones, digital devices and the Internet of Things. It can significantly reduce the quantities of chemicals used in the food system.

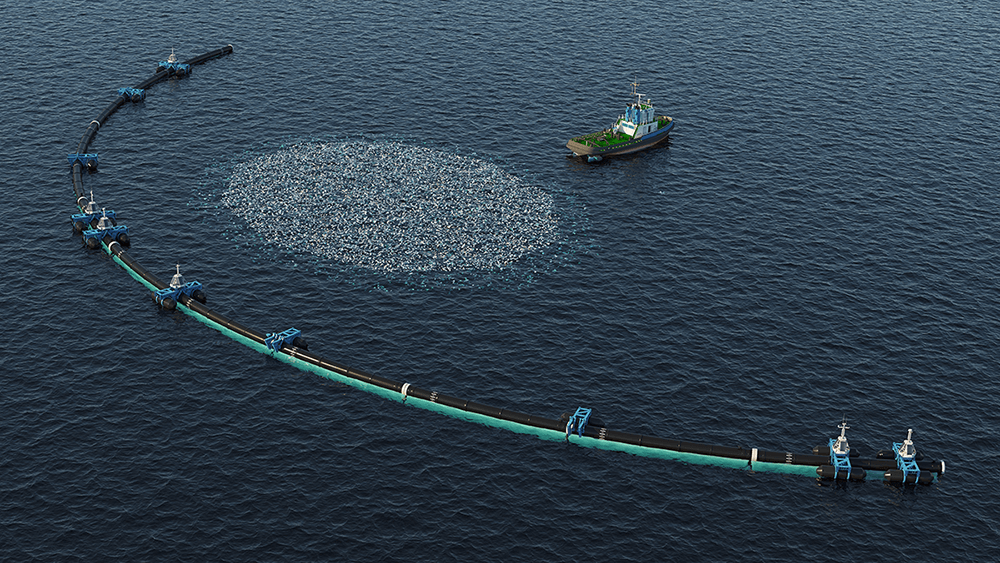

Market-based solutions could help as well. Water quality trading schemes, for instance, allow industrial and agricultural water users to buy and sell water rights at a variable price based on pollution levels, creating a financial incentive to lower pollution or treat polluted wastewater. While innovation can bring down the cost of more sustainable alternatives, changes to pricing and financial markets can help raise the cost of pollution.

In the end, what is needed to confront chemical pollution will look much like that of energy and emissions: a bold combination of tightening regulation, consumer pressure, innovation and more responsible, environmentally engaged industrial partners, to tackle the planetary challenge that will dominate this century.

Read more on the Plastic Management Index which examines plastic management through the lens of policy, regulation, business practice and consumer actions at a country level.

Back to Blue is an initiative of Economist Impact and The Nippon Foundation

Back to Blue explores evidence-based approaches and solutions to the pressing issues faced by the ocean, to restoring ocean health and promoting sustainability. Sign up to our monthly Back to Blue newsletter to keep updated with the latest news, research and events from Back to Blue and Economist Impact.

The Economist Group is a global organisation and operates a strict privacy policy around the world.

Please see our privacy policy here.

THANK YOU

Thank you for your interest in Back to Blue, please feel free to explore our content.

CONTACT THE BACK TO BLUE TEAM

If you would like to co-design the Back to Blue roadmap or have feedback on content, events, editorial or media-related feedback, please fill out the form below. Thank you.

The Economist Group is a global organisation and operates a strict privacy policy around the world.

Please see our privacy policy here.

World Ocean Summit & Expo

2025

World Ocean Summit & Expo

2025 UNOC

UNOC Sewage and wastewater pollution 101

Sewage and wastewater pollution 101 Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution

Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC

Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC