The next key step will be scheduling the ‘INC 5.2’ talks. Despite the lack of a formal meeting date, stakeholders will continue preparatory work to advance the treaty’s objectives and lay the groundwork for more productive negotiations. “Nature and human health can’t afford to wait, so it’s concerning that it’s being kicked further down the road,” says Mr Lindebjerg. “This was a wake-up call for countries, and now they have to figure out how to deliver a treaty, whether through consensus, voting or a treaty among the willing, and do it.”

Public awareness on the connection between health and plastics has improved significantly over the course of five rounds of talks, another benefit to the INC process despite the lack of a deal yet. “It’s very important that the human health perspective is now fully acknowledged as a concern,” says Ms Fiscina. “In the two years [of the INC process], we’ve learned so much more about the health situation and we understand the full scope of the problem far beyond what we originally understood, which has been a success in a way. If we make sure that we have all the scientific evidence in hand, we can reach a solution sooner.”

Scientists, advocates and a majority of countries are now in agreement that something needs to be done. But this has caused even more frustration for the observers, who feel that this powerful movement is being held back.

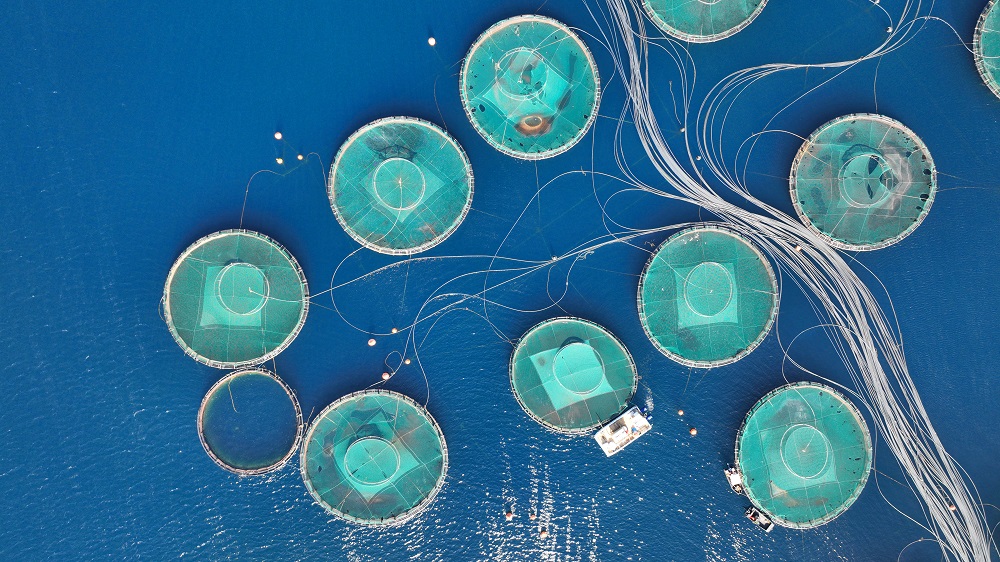

The scourge of untreated wastewater

The scourge of untreated wastewater Slowing

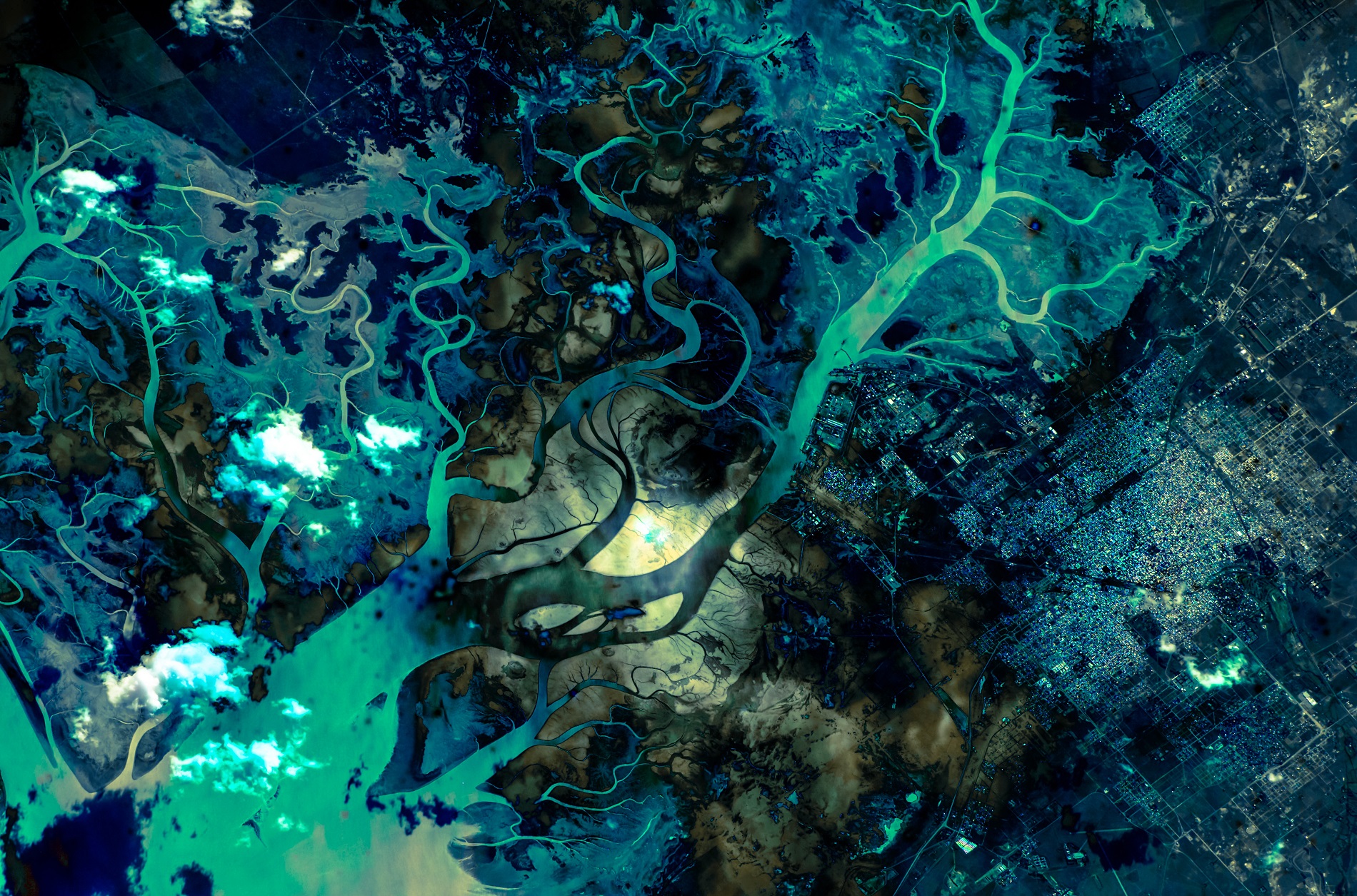

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution

Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC

Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC