Since the UN Environment Assembly adopted a resolution to tackle the global plastics pollution crisis in 2022, experts and activists have debated how to bring dissenting voices together and what the outcome of a global treaty on plastic pollution treaty should be. If the treaty is to address the full lifecycle of plastics, negotiators will need to grapple with the economic model that underpins the plastics industry.

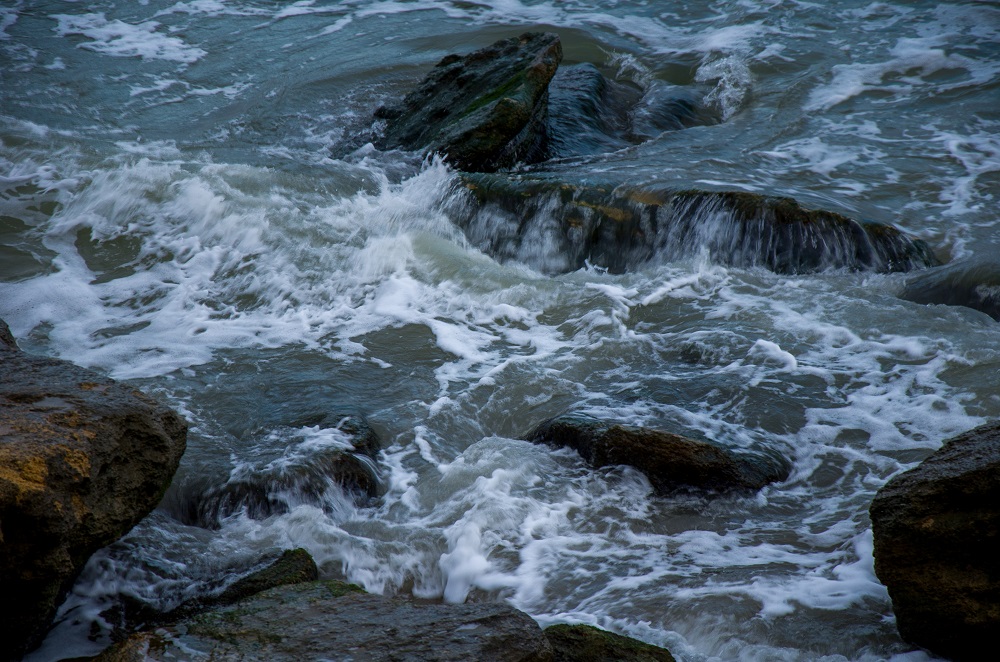

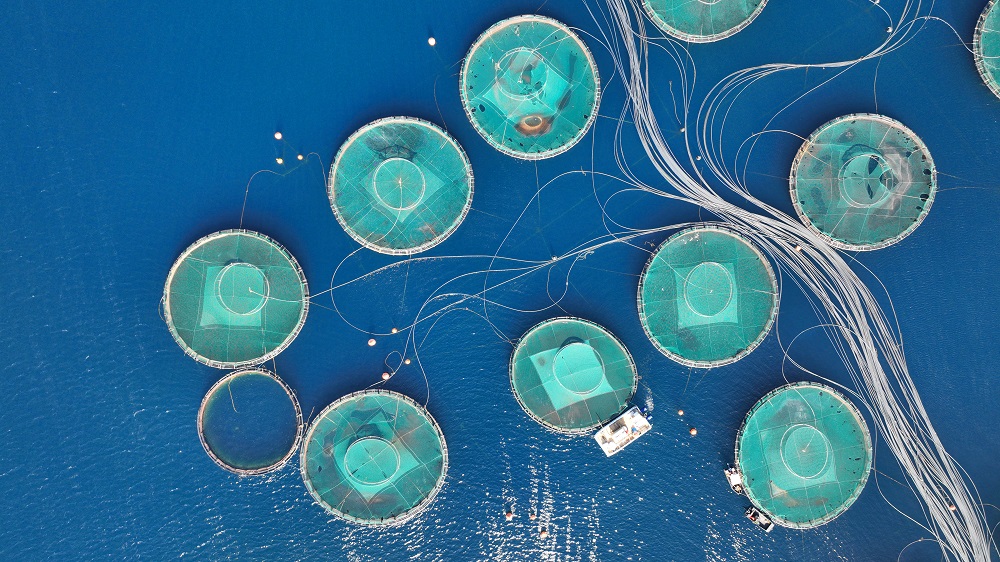

Plastic touches almost every aspect of our lives, bringing convenience, cost savings and versatility to our economies and societies. But it has also accumulated in landfills and oceans. Its negative impacts on the environment, human health, and the economy remain grossly unaccounted for in the price of virgin plastic.

Transitioning to a new plastics model that accounts for these externalities will be expensive, but the cost of inaction will likely be far higher. The cost of plastic on the environment and society could be tenfold what it reaches on the market. Without action, the annual flow of plastic into oceans could nearly triple by 2040. This is a high price tag for a seemingly cheap material.

How to fund the treaty’s implementation and create incentives that encourage the transition to a new plastic economy will be critical to the treaty’s success. Policymakers will need a toolkit of policy levers and market-based instruments that will enable them to simultaneously curb plastic production, create new markets for alternative products, drive responsible consumption and ultimately unlock the potential of a circular plastics economy.

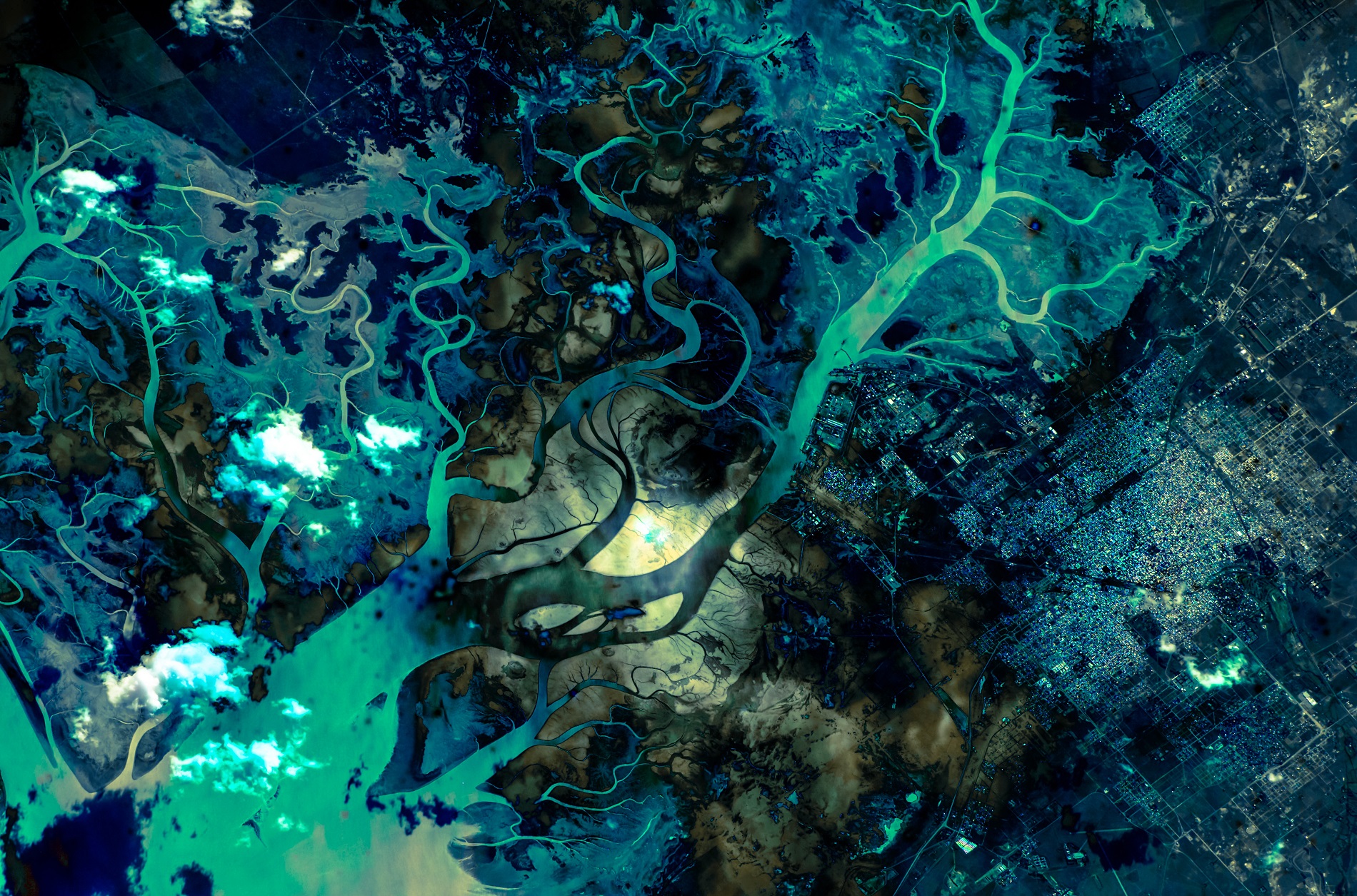

The scourge of untreated wastewater

The scourge of untreated wastewater Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution

Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC

Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC