AFFILIATED CONTENT

This article is written by Yoni Shiran, a partner at Systemiq and the lead author of Breaking the Plastic Wave and Jakob Franke, an associate at Systemiq and a policy expert.

World leaders have finally woken up to the fact that a global strategy is needed to address one of the biggest environmental threats facing our planet: plastic pollution. In March 2022 UN member states agreed to negotiate a new legally binding global plastics treaty; the first round of talks will take place in Uruguay from November 28th. This is an unmissable chance to shift from today’s dangerous business-as-usual pathway, but it must be the right kind of treaty—one that really tackles the plastic problem.

It took years for the world to reach the ground-breaking Paris Agreement on climate change, while COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh proved once again how hard it is to reach a global consensus on complex challenges. But the plastics crisis needs more than a Paris Agreement-style treaty requiring countries to commit to action on a national level. As plastic is a physical material that moves across boundaries, the global plastics treaty should include internationally agreed priorities and require close alignment between states. Without legally binding global commitments and effective cross-border co-operation, our efforts to fight plastic pollution will fail.

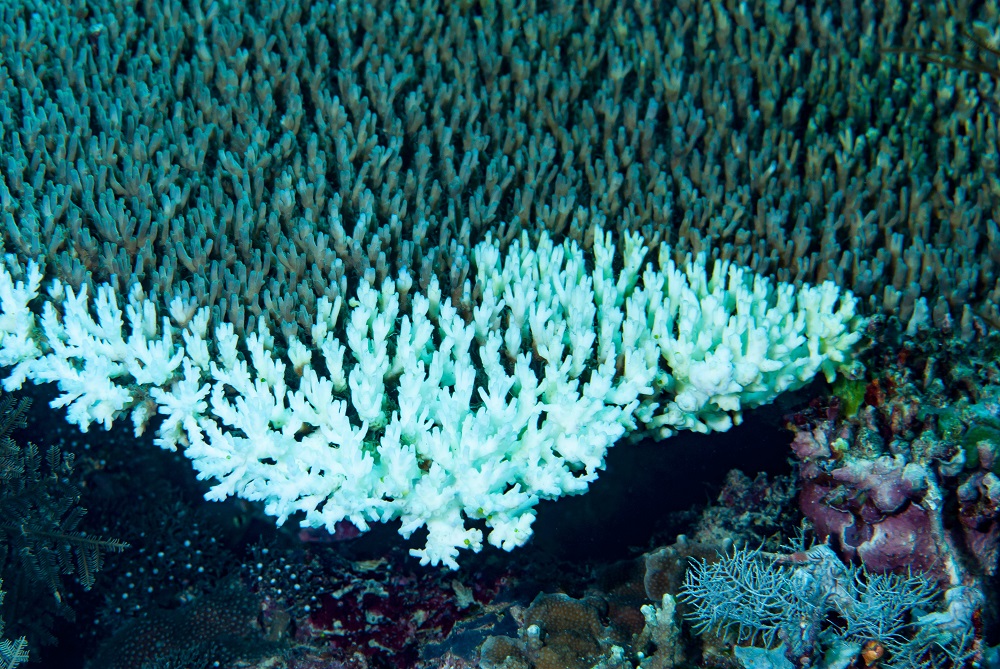

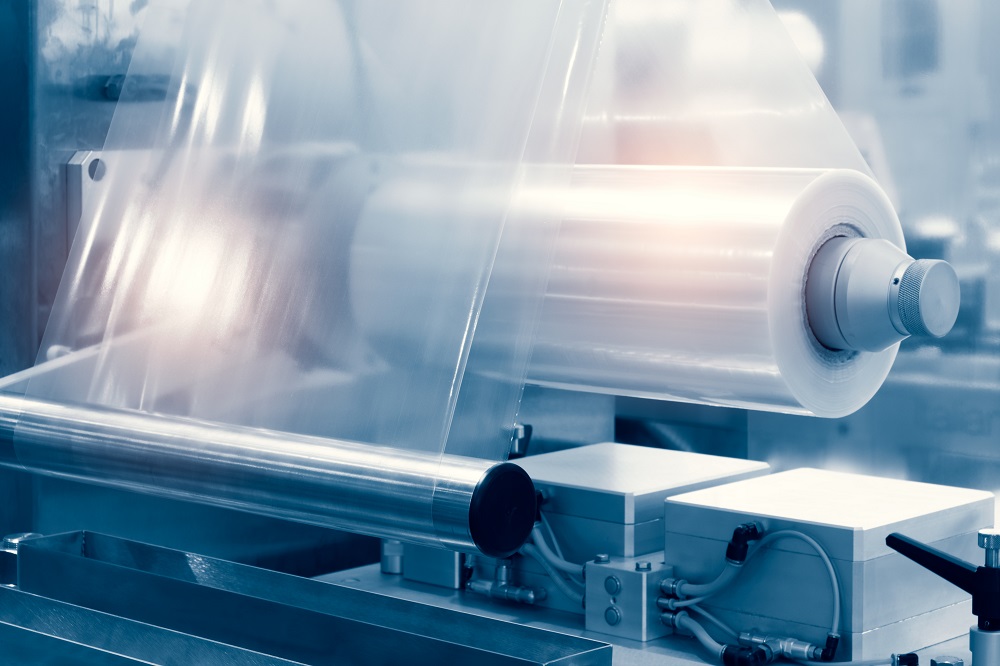

Plastic is valued for its consumer benefits—affordability, convenience, durability—but the way this material pollutes the ocean and other ecosystems has provided a cautionary tale of how linear consumption models can undermine Earth’s planetary limits. Unless we take global action, by 2040 plastic production will double, its pollution in the environment will nearly triple, and waste in the ocean will more than quadruple. It’s a by-product of a fundamentally flawed system in which 95% of the value of plastic packaging—worth US$80bn-120bn a year—is lost to the economy after a single, short use.

The solution is to build a zero-waste circular plastic economy that designs out waste, eliminates unnecessary production and consumption, and safely collects and recycles plastic that cannot be eliminated. This will permanently stop plastic pollution, increase material circularity, and cut greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions—a win-win-win scenario. But there is no silver bullet to achieve this vision. We cannot ban or recycle our way out of the plastics crisis. We need a full spectrum of circular economy solutions: better design, sustainable substitute materials, improved collection, more efficient recycling, and so on. These components should be implemented concurrently, ambitiously, and starting immediately. It won’t be easy, but it is doable if we act together and with ambition.

The good news is that a critical mass of stakeholders agrees that we need a global treaty. And leaders across the public and private sectors are making emotive promises to do everything they can to tackle plastic pollution. But a coherent global strategy to solve this growing crisis remains elusive. There are widely different views on what the treaty’s ambition, objective, scope and mechanisms should be, and we even risk ending up with a treaty that is less ambitious than current voluntary efforts.

A strong global target translated into national commitments and action plans, like the Paris Agreement, would be a big step forwards. But the global plastics treaty needs to go “beyond Paris” and incorporate legally binding global measures to accelerate progress at a country level. Implementing a Paris-style Agreement would miss a fundamental point: plastic is radically different from GHG emissions because it is a physical material that’s actively traded and moved across borders. This means that the countries where plastics are used and disposed of are affected by decisions made in the nations that design and produce plastics. That’s why plastic requires strong international alignment on design standards, priority policies, monitoring and reporting mechanisms.

Member states should agree to a legally binding global treaty with five crucial components. First, a global target to end plastic pollution by 2040. Second, a list of priority policies that all member states implement harmoniously. For example, the treaty should include a list of problematic plastics not to be used for certain purposes and mandatory criteria for national Extended Producer Responsibility policies to fund recycling and waste management and incentivise reduction, reuse, and re-design. Third, the treaty should create monitoring and reporting mechanisms that define what information needs to be disclosed by countries and companies. Fourth, we need a funding mechanism to support poorer countries to build the necessary infrastructure for waste collection and recycling. After decades of designing and selling hard-to-recycle products around the world, richer nations must commit to providing the support and means of implementation needed to address their plastics legacy. Finally, we need national action plans to implement commitments and align all stakeholders on a course of ambitious action.

The global plastics treaty needs to go beyond Paris by clearly setting out the foundations and mechanisms to transform the global plastic system. While national action plans on plastic pollution are clearly part of the answer, they cannot be the full answer because in isolation they will not be enough to end the global scourge of plastic pollution. Negotiators of the global plastics treaty must aim high. There won’t be a second treaty.

Yoni Shiran is a partner at Systemiq and the lead author of Breaking the Plastic Wave

Jakob Franke is an associate at Systemiq and a policy expert

[email protected]

Back to Blue is an initiative of Economist Impact and The Nippon Foundation

Back to Blue explores evidence-based approaches and solutions to the pressing issues faced by the ocean, to restoring ocean health and promoting sustainability. Sign up to our monthly Back to Blue newsletter to keep updated with the latest news, research and events from Back to Blue and Economist Impact.

The Economist Group is a global organisation and operates a strict privacy policy around the world.

Please see our privacy policy here.

THANK YOU

Thank you for your interest in Back to Blue, please feel free to explore our content.

CONTACT THE BACK TO BLUE TEAM

If you would like to co-design the Back to Blue roadmap or have feedback on content, events, editorial or media-related feedback, please fill out the form below. Thank you.

The Economist Group is a global organisation and operates a strict privacy policy around the world.

Please see our privacy policy here.

World Ocean Summit & Expo

2025

World Ocean Summit & Expo

2025 UNOC

UNOC Sewage and wastewater pollution 101

Sewage and wastewater pollution 101 Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution

Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC

Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC