On July 19th 1979, the waters off Tobago's coast became the setting for a now-historic disaster. The supertankers Atlantic Empress and Aegean Captain collided, releasing nearly 287,000 tonnes of crude oil into the Caribbean Sea. At the time, this was the largest tanker-based oil spill in history, and its devastation echoed across the Caribbean. Fisheries collapsed, tourism was threatened and the livelihoods of communities relying on marine and coastal resources were put at risk.

The incident illustrated both the vulnerability and the interconnectedness of Caribbean states, at a time when the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) was laying the foundations for co-operation through its nascent Regional Seas Programme.

Caribbean leaders seized the opportunity, formally requesting UNEP’s support to establish a regional mechanism to protect the Caribbean Sea. The Cartagena Convention was adopted in 1983, alongside its first protocol, the Oil Spills Protocol, which entered into force in 1986. Its Secretariat was established in Kingston, Jamaica.

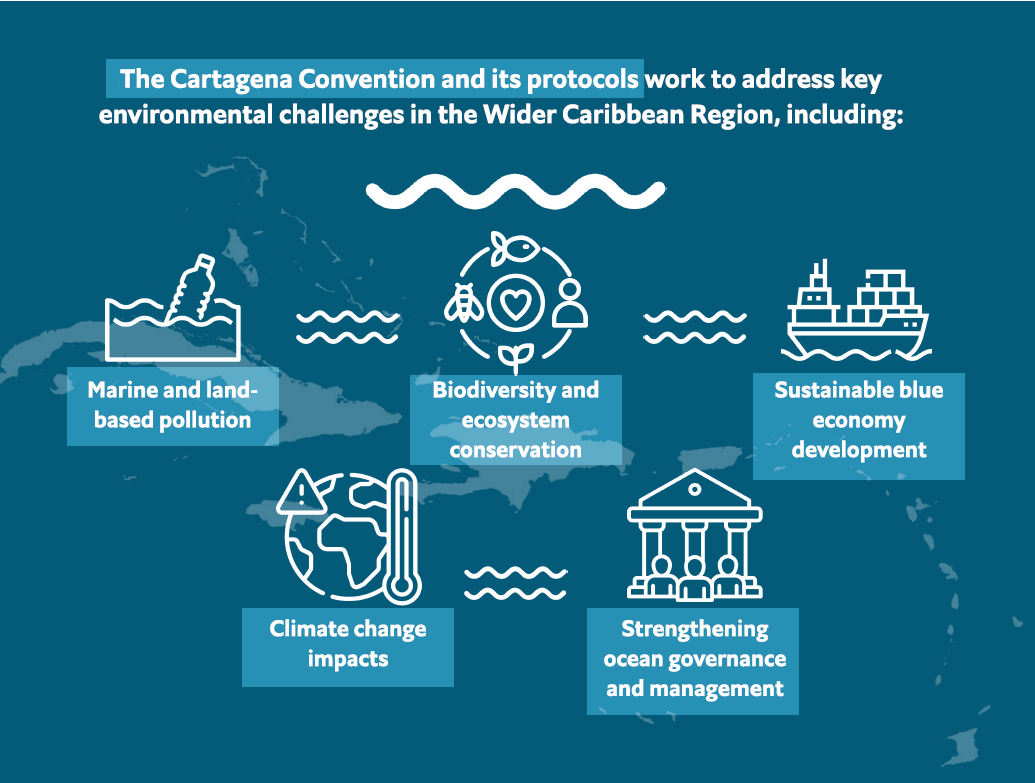

From its origins in response to an oil spill, the Cartagena Convention has since evolved into a comprehensive governance framework, balancing legal commitments with non-binding strategies and offering enduring lessons for governance efforts to tackle ocean pollution worldwide.

Governance: a regional approach to a shared sea

The Cartagena Convention stands as the only legally binding regional environmental agreement for the Wider Caribbean Region. Its scope spans from the US and Mexico to the smallest islands of the Lesser Antilles, creating a platform where vastly different countries—continental and island, resource-rich and resource-constrained—collaborate on shared challenges.

Under the Convention, countries come together through technical working groups and inter-governmental meetings to address issues such as marine biodiversity protection, fisheries management, pollution control and coastal zone management. This process encourages dialogue between countries with different capacities and economic backgrounds, creating opportunities for harmonisation and regional decision-making without compromising national sovereignty.

Not only is this model inclusive, but it’s also practical. No single Caribbean country can tackle challenges such as plastic pollution, Sargassum influxes or trans-boundary oil spills on its own. Regional co-operation is not a choice; it’s a necessity.

Towards an ocean free from the harmful impacts of pollution

Back to Blue, an initiative of Economist Impact and The Nippon Foundation, has worked with experts from science, industry, policy, finance and the UN to develop solutions to address ocean pollution. A Global Ocean Free from the Harmful Impacts of Pollution: Roadmap for Action offers a framework to catalyse collective action.

In response, the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO (UNESCO-IOC) and the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) are proposing a multi-decade partnership as part of the UN Ocean Decade (2021–2030). Their vision: to build a strong evidence base, close data gaps and spur decisive public- and private-sector action by 2050.

Realising this ambition will require UN member states to collaborate ever more deeply. The Cartagena Convention offers a model for co-operation that, if replicated in other regions, could spearhead the global effort to tackle ocean pollution.

From oil spills to land-based sources: recognising root causes

The Oil Spills Protocol, the Convention’s first significant instrument, focused on preparedness and response to spills from maritime transport, while enhancing the capacity of member states to manage marine-based incidents. Reflecting on this experience 25 years on, Christopher Corbin, co-ordinator of the Cartagena Convention Secretariat, explains that the Secretariat and its member states quickly realised that to effectively address pollution in the Caribbean Sea, they would need to target its sources. “We realised that restoration efforts were failing because the root causes of land-based pollution weren’t being addressed,” Mr Corbin says.

In 1999, the Protocol on Land-Based Sources of Marine Pollution (LBS) was adopted, coming into effect in 2010. The LBS Protocol highlighted two key priorities: untreated wastewater and agricultural run-off, pollutants that directly impact human health, coral reefs, mangroves and seagrass beds: ecosystems crucial for fisheries and tourism.

Over time, new priorities have emerged. Plastic pollution, nutrient overload and the cumulative effects of climate change have become more pressing issues. The Convention has integrated circular economy strategies, clean technology and nature-based solutions, says Mr Corbin, ensuring it adapts to new threats while addressing the fundamental causes of ocean pollution. The shift has been driven by scientific and monitoring advancements, as well as the need for practical, resource-efficient solutions for the Caribbean region.

Legal commitments: catalyst and constraint

One of the Convention’s key features, distinguishing it from many other regional approaches to addressing ocean pollution, is its legally binding nature. Signatory governments commit to specific actions under the Convention and its protocols through Decisions of Conferences of Parties. This can give impetus to local reforms and catalyse international funding, Mr Corbin explains. “The legal framework has incentivised, encouraged and in some cases stimulated action at the national level,” he says. Governments can reference these commitments when justifying investments in wastewater treatment, pollution control or biodiversity protection to their domestic constituents. Countries can appeal to donors by citing related international obligations, strengthening their case for financial support.

Yet legal instruments are not a panacea. Mr Corbin emphasises that much of the Convention’s success stems from the process of bringing governments together, including the use of non-binding instruments such as technical guidelines, best practices and regional strategies. “The act of bringing different views to the table and coming up with scientific and technical solutions is just as valuable as the legal framework itself,” he insists. This balance of binding commitments for accountability, complemented by flexible, non-binding co-operation, has become a hallmark of the Cartagena Convention, and may offer lessons for other regions.

A bottom-up governance model

Unlike treaties that impose uniform obligations, the Cartagena Convention allows each nation to articulate its own priorities before building regional consensus. “The idea is coherence and consistency,” Mr Corbin explains, “but with enough flexibility for each country to tweak and customise to its own local circumstances.” The Convention actively engages national governments and technical representatives from each member state to identify their unique priorities, whether related to marine biodiversity, fisheries, coastal management or pollution control.

This inclusive process ensures that regional strategies are shaped by the needs and perspectives of all participating countries, fostering greater participation and ownership. The success of this model is built not only on formal procedures but also on the personal connections and trust that have developed, making the collaboration feel more like a family than a government process. By prioritising national voices and encouraging broad stakeholder engagement, the Convention can develop more practical and widely supported solutions to shared environmental challenges.

Breaking silos: governments, civil society and the private sector

The Convention has also helped signatories evolve their approaches to managing ocean pollution at the national level, says Mr Corbin. Previously, ministries of environment, agriculture, tourism, health and finance often worked independently, hindering member states’ abilities to implement effective and integrated environmental policies. The Convention has helped bridge these gaps, Mr Corbin notes.

This has led to improvements, he says. Several governments have established national inter-ministerial committees, blue economy ministries and co-ordinating ministries of environment, and “we’ve seen as a Secretariat that this has helped with collaboration”. Stronger national co-ordination has proven particularly critical in tackling land-based sources of ocean pollution, where solutions often lie far upstream from coastal zones.

Community groups and environmental non-governmental organisations now play their part in the process, too. They’ve been accredited as observers to the Convention and are participating in meetings between governments, helping to shape the debate. This move adds legitimacy and ensures local knowledge informs the Convention’s work. However, Mr Corbin stresses the need for more private-sector involvement, pointing out that their input is crucial for developing effective solutions to marine pollution. Cruise companies, shipping firms and hotel chains, for example, have a significant impact on marine pollution, particularly when it comes to wastewater discharge and coastal development, yet they “rarely get a chance to contribute to policy discussions and the design and implementation of sustainable solutions,” says Mr Corbin.

Progress is being made, with regional efforts led by the Secretariat to engage with tourism associations and shipping groups. Importantly, Mr Corbin sees an opportunity for the proposed UN Ocean Decade programme to lead the effort to engage businesses more systematically at a global level.

Data, monitoring and the knowledge gap

Effective ocean governance relies on accurate and timely data; however, many Caribbean states still rely on outdated monitoring systems and lack the necessary resources for comprehensive assessments. Many national monitoring programmes are “very outdated, and based on very old science,” explains Mr Corbin. “There’s certainly a need for greater capacity-building.”

He is optimistic about the significant opportunities offered by emerging technologies, such as remote sensing, satellite imagery and artificial intelligence, which are becoming increasingly accessible. “However, just having the technical data alone is not going to be enough,” he adds. “It has to be transformed into knowledge products and decision-support tools.” The Secretariat has attempted to fill the data gap by developing regional platforms that compile data and translate it into infographics and policy briefs, but capacity remains a limiting factor. Collaboration with universities and research institutes is another key priority; applied research can help identify pollution sources and test solutions, while academic partnerships build regional expertise.

The real challenge isn’t just about collecting data, Mr Corbin says, but about using it to inform decision-making about where to build wastewater treatment plants, which technologies to adopt and how to create policies that balance environmental protection with development goals. The Convention has achieved some successes in this regard: assessments of wastewater treatment infrastructure in various regions have revealed significant gaps in coverage, which have directly influenced national investment strategies. Likewise, pilot projects using satellite imagery to monitor plastic and Sargassum blooms have provided early warnings to coastal communities and tourism operators.

Ultimately, Mr Corbin is keen to stress that, “even when we have the data, it is not [always] being adequately transformed into knowledge products and decision-support tools.” This issue highlights a key lesson for the proposed UN Ocean Decade programme: investing in data is not enough; the priority must be transforming it into accessible, actionable knowledge that supports decision-making.

Supporting global environmental commitments

Beyond its regional mandate, the Cartagena Convention plays an important role in helping member states fulfil commitments made under other related multilateral environmental agreements, explains Mr Corbin. The Convention’s protocols and projects are aligned with global frameworks, including the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and other pollution-related conventions such as the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL) and the Basel Convention. “We’ve done a comparative analysis between our regional convention and other global Middle East and Africa commitments, including the SDGs,” he says. “I’ve certainly seen a significant amount of alignment.”

This alignment enables the Secretariat to help governments fulfil multiple obligations simultaneously. As Mr Corbin explains, “In providing them with the technical and capacity-building support, and in some cases financial support through externally funded projects, not only are they meeting their obligations under the Cartagena Convention and its protocols, but at the same time, we are contributing to them also achieving some of these global targets as well.” He emphasises the link between the Convention’s Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife Protocol (SPAW; adopted in 1990, entered into force in 2000) and biodiversity commitments such as the CBD’s 30 by 30 target: “We cannot have effective marine biodiversity conservation if we are not also addressing the stressors of those coastal and marine resources.”

Lessons for the UN Ocean Decade Programme

The Cartagena Convention provides a set of clear and transferable lessons for the proposed UN Ocean Decade Programme on Ocean Pollution:

- Bottom-up flexibility: By starting with national priorities, the Convention fosters ownership and ensures that regional action is grounded in reality. A global programme should respect local contexts rather than impose one-size-fits-all mandates.

- A blend of legal and non-legal tools: Binding commitments create accountability and unlock resources, while non-binding strategies foster innovation and consensus.

- Integration of anti-pollution initiatives with other commitments, such as 30 by 30: The Caribbean experience shows that pollution cannot be addressed in isolation. Global programmes must link pollution to states’ existing commitments on climate change, biodiversity and sustainable development.

- Translate science into usable knowledge: Policymakers need decision-support tools, not raw data sets. Transforming technical information into accessible and timely products should be a priority.

- Storytelling and visibility: As Mr Corbin notes, “The region has wonderful stories to tell, but no global platform [on which] to share them.” A global programme should invest in amplifying success stories to inspire broader action.

- Partnership of partnerships: The Convention demonstrates the power of relationships. Governments, UN agencies, scientists, civil society and the private sector can accomplish more together than they can individually.

Conclusion: A blueprint for collective action

The Cartagena Convention exemplifies the potential of regional governance to address a complex and multi-faceted challenge such as ocean pollution. Anchored in law yet flexible in practice, it has evolved from oil-spill response to a comprehensive framework that integrates pollution, biodiversity and livelihoods. Its bottom-up approach fosters national ownership while ensuring regional coherence, and its combination of legal obligations and voluntary co-operation offers a pragmatic template for action. Ultimately, the Convention’s success is a testament to the power of human connection, demonstrating that collective action is most effective when built on relationships of trust that feel more like a family than a formal process, says

Mr Corbin. The Convention also highlights gaps, particularly in private-sector engagement, data capacity and storytelling, that the proposed UN Ocean Decade Programme on Ocean Pollution has the potential to address.

The lesson from the Caribbean is ultimately one of possibility. Collective action is not easy, but it is achievable when grounded in science, supported by law and animated by partnerships. By building on this model, the global community has a chance to deliver on the ambition of a clean, healthy ocean by 2050.

EXPLORE MORE CONTENT ABOUT THE OCEAN

Back to Blue is an initiative of Economist Impact and The Nippon Foundation

Back to Blue explores evidence-based approaches and solutions to the pressing issues faced by the ocean, to restoring ocean health and promoting sustainability. Sign up to our monthly Back to Blue newsletter to keep updated with the latest news, research and events from Back to Blue and Economist Impact.

The Economist Group is a global organisation and operates a strict privacy policy around the world.

Please see our privacy policy here.

THANK YOU

Thank you for your interest in Back to Blue, please feel free to explore our content.

CONTACT THE BACK TO BLUE TEAM

If you would like to co-design the Back to Blue roadmap or have feedback on content, events, editorial or media-related feedback, please fill out the form below. Thank you.

The Economist Group is a global organisation and operates a strict privacy policy around the world.

Please see our privacy policy here.

The scourge of untreated wastewater

The scourge of untreated wastewater Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution

Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC

Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC