Time is running out to avoid the worst impacts of ocean acidification on marine life, livelihoods and economies. A climate-change impact on the ocean, alongside warming seas and deoxygenation, ocean acidification is belatedly finding its way onto the global climate and ocean agendas, even as the gravity of its impact on ocean health and on the stability of the ocean as a vital earth system remains underappreciated.

A Back to Blue roundtable discussion at the World Ocean Summit Asia-Pacific, led by Charles Goddard, editorial director at Economist Impact and supported by the Nippon Foundation, explored the state of the science on ocean acidification and the most promising approaches to remediation. The key takeaways from the session were as follows:

The science is clear: the ocean is becoming more acidic, threatening marine life and health, and undermining the planet’s ability to fight climate change

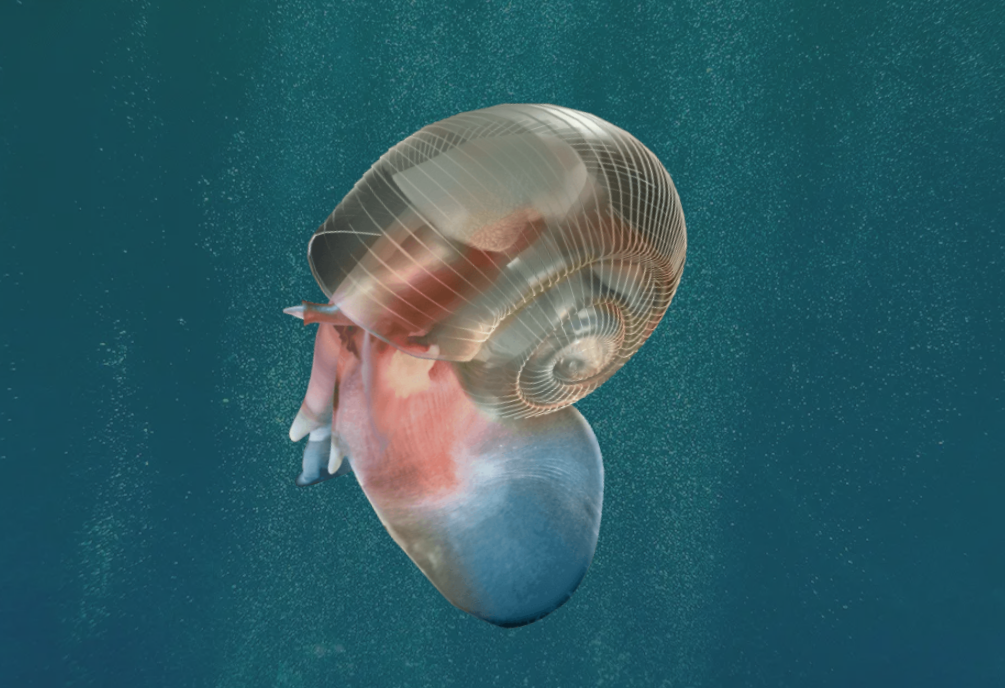

The ocean absorbs around one-third of the carbon dioxide produced by humans; the absorbed carbon dioxide then reacts with seawater to create carbonic acid, resulting in an increase in the acidity of the ocean. The open ocean is 40% more acidic than before the industrial revolution.

This is weakening the ability of marine organisms that rely on calcium carbonate to build their shells and skeletons. Marine organisms also have to use more energy to deal with environmental stresses, as energy is drawn away from growth and reproduction, threatening species sustainability. Evidence also shows that acidification is more variable and extreme in coastal areas due to the interactions with rivers and the seabed. This is worrying because coastal areas are where human interactions with oceans and goods and services provided are more heavily relied on.

Rapid action to redress acidification is needed, but geoengineering approaches need to be carefully tested before being conducted at scale.

A rapid reduction in carbon emissions is clearly a priority to protect our ocean from further harm, but carbon dioxide removal techniques should also be explored in earnest to offer a faster, more scalable route. These range from nature-based solutions such as restoring or nurturing mangroves which increase alkalinity to more radical approaches like ocean iron fertilisation, a technique based on the theory that stimulating phytoplankton growth with iron increases atmospheric carbon absorption into the ocean, as part of the biological pump system. Such projects are now already underway, having been more theoretical in the past, but there is no global discussion about what techniques are acceptable and who controls implementation.

There are concerns that some projects, like blue carbon habitats, are not quick fixes and could take many years to come to fruition, while more radical, faster interventions could have unanticipated negative effects. Ocean iron fertilisation, for instance, could lead to downstream effects, such as robbing nutrients from ecosystems many miles away. Scientists have also revealed side-effects like the creation of new toxins that could alter the marine food web, for example.

The most promising interventions are those which restore ocean habitats to their natural state in which they can be highly effective carbon sinks. Moreover, ongoing human activities continue to thwart the ocean’s carbon dioxide-reducing function and should be tackled. The seafloor, for instance, sequesters huge amounts of CO2 but bottom trawling and certain fishing practices disturb this process. Our activities in the ocean are slowing down the natural sequestration process.

Ocean acidification needs to be made relevant at the local level.

Ocean acidification is not well-understood, in layman’s terms, at the local community level. In geographies where scientific capacity is limited, citizen science and participation is key. In the Maldives, experts actively engage with fishers and communities to guide them on what to look out for, and on activities they should and should not engage in at specific times, like dredging. Acidification needs to be framed in relevant ways, like the dissolution of coral reefs which impacts fisheries and tourism, which would gain more attention from those who use the ocean daily.

Vulnerable countries need funding for regulation and monitoring and to build capacity to lead the science

Geopolitical factors and regional engagement are crucial to a well-coordinated response to ocean health, as actions at individual nation level are undermined by lower standards elsewhere. The Maldives has among the most sustainable tuna fishing industries in the world, using pole and line approaches, but this is a migratory species and if there are nearby trawlers, the country’s efforts are diluted. Several speakers said there was a need for more public funding and support, and crucially, efforts to help countries generate the science, knowledge and evidence they need on ocean sustainability, rather than relying on academic researchers in the global North.

Ocean literacy is critical - and that starts at school.

We need to do a better job of educating the public about the vital role the ocean plays in the planet’s survival and our own existence. In school and the early years, for example, attention is paid to species like endangered tigers and pandas, but not Prochlorococcus, the tiny bacteria whose photosynthetic activities produce 20% of the oxygen in the biosphere.

The need for strategic planning to guide priorities and enable innovations like blue finance to scale

There needs to be an overarching approach involving strategic planning across monitoring, capacity-building and solutions. Marine spatial planning, for instance, can help us identify hotspots and vulnerable ecosystems that should be prioritised for protection or to restore the function of oceans to sequester carbon. Blue finance also needs standards and tools to identify risky versus sustainable blue economic activities to enable investors to make the right choices.

Back to Blue is an initiative of Economist Impact and The Nippon Foundation

Back to Blue explores evidence-based approaches and solutions to the pressing issues faced by the ocean, to restoring ocean health and promoting sustainability. Sign up to our monthly Back to Blue newsletter to keep updated with the latest news, research and events from Back to Blue and Economist Impact.

The Economist Group is a global organisation and operates a strict privacy policy around the world.

Please see our privacy policy here.

THANK YOU

Thank you for your interest in Back to Blue, please feel free to explore our content.

CONTACT THE BACK TO BLUE TEAM

If you would like to co-design the Back to Blue roadmap or have feedback on content, events, editorial or media-related feedback, please fill out the form below. Thank you.

The Economist Group is a global organisation and operates a strict privacy policy around the world.

Please see our privacy policy here.

World Ocean Summit & Expo

2025

World Ocean Summit & Expo

2025 UNOC

UNOC Sewage and wastewater pollution 101

Sewage and wastewater pollution 101 Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution

Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC

Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC