Native science sits at the core of the Green Renaissance, a term I use for the alignment of ecological intelligence with modern technology, and the possibility of a more regenerative future. The bioeconomy—spanning food, materials, health, energy and ocean industries—is already valued at around US$4trn and could reach US$30trn by 2050. More than half of global GDP is moderately or highly dependent on nature and its services. Yet the knowledge that governs those systems—from biodiversity insights to long-standing ecological practices—remains largely absent from the strategies shaping markets and innovation.

This is region-specific, empirically tested systems knowledge held by coastal populations—long-range pattern recognition, resource logic and biological engineering practiced over thousands of years. Scientific in method, cultural in expression and global in relevance, it remains one of the most valuable and least-priced assets on the planet. Overlooking it is an innovation bottleneck, a market inefficiency and a strategic error in an era when the bioeconomy depends on evolutionary intelligence that cannot be synthesised in labs.

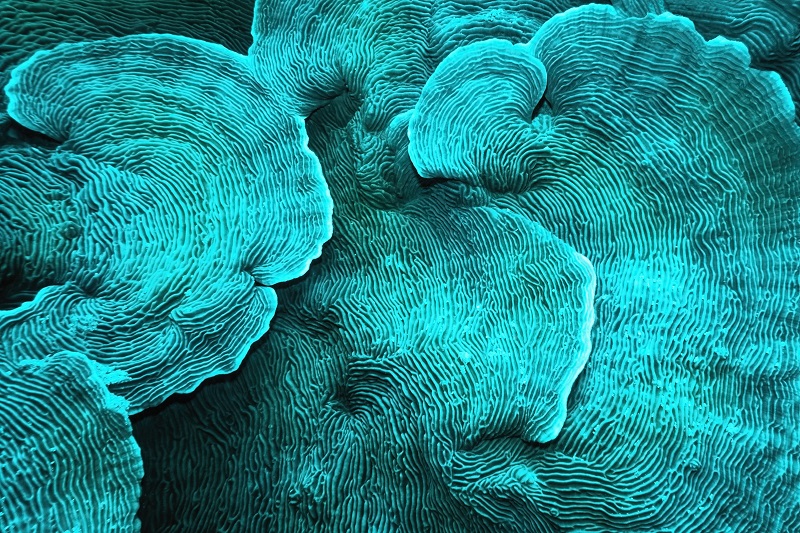

The irony is that the very systems investors now chase — resilience, efficiency, circularity — were already advanced and practiced by maritime societies, whose expertise was never recognised in formal economic frameworks. Consider what marine and amphibious biodiversity has already unlocked. Salamanders can regenerate limbs and spinal tissue, and their biology is now informing early research in human nerve repair. Engineers study squid propulsion to develop prosthetics with fluid movement that current robotics cannot replicate. Sharkskin’s hydrodynamic properties inspired automotive drag reduction and competitive swimsuit design. Marine cone snails from Indo-Pacific reefs produce the compounds behind Prialt, a pain medication up to 1,000 times more powerful than morphine. Invasive lionfish are being processed into leather alternatives. Seaweed is replacing petroleum-based plastics in packaging and textiles.

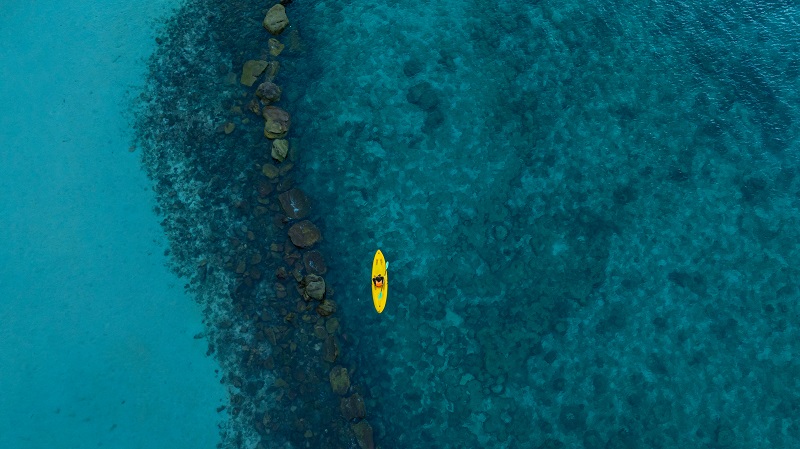

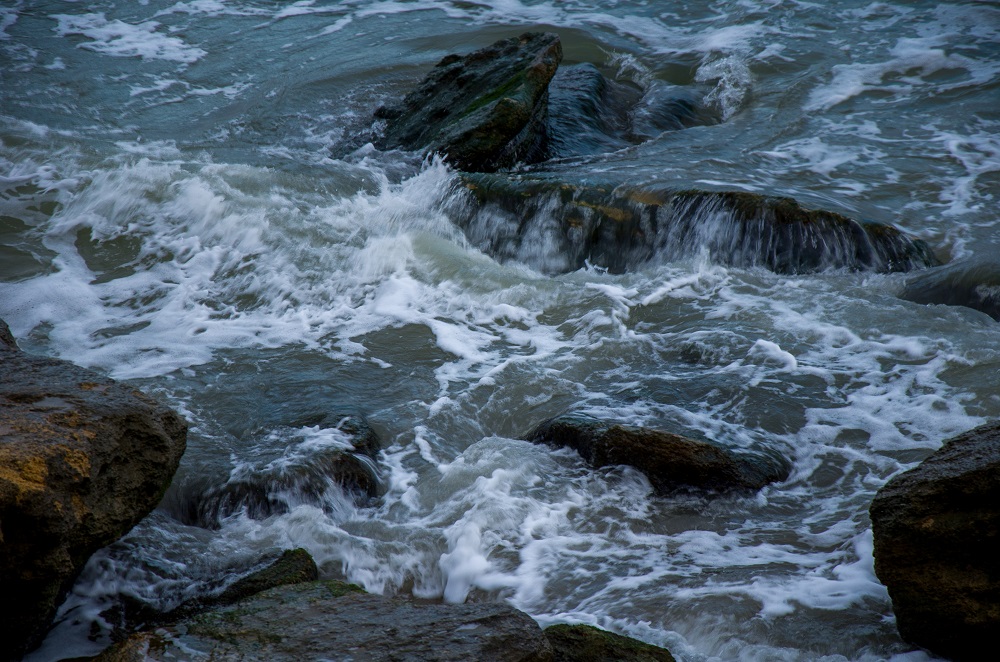

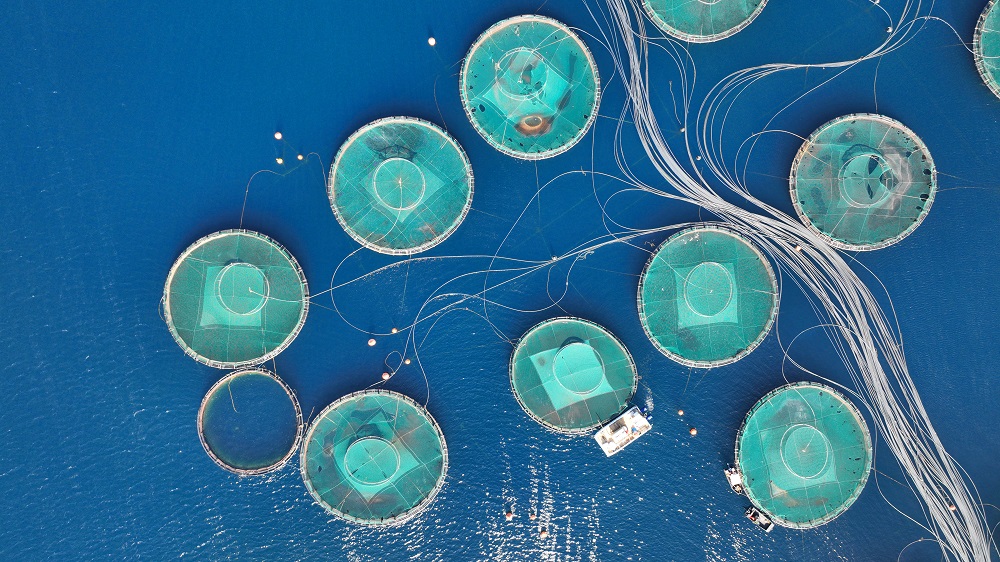

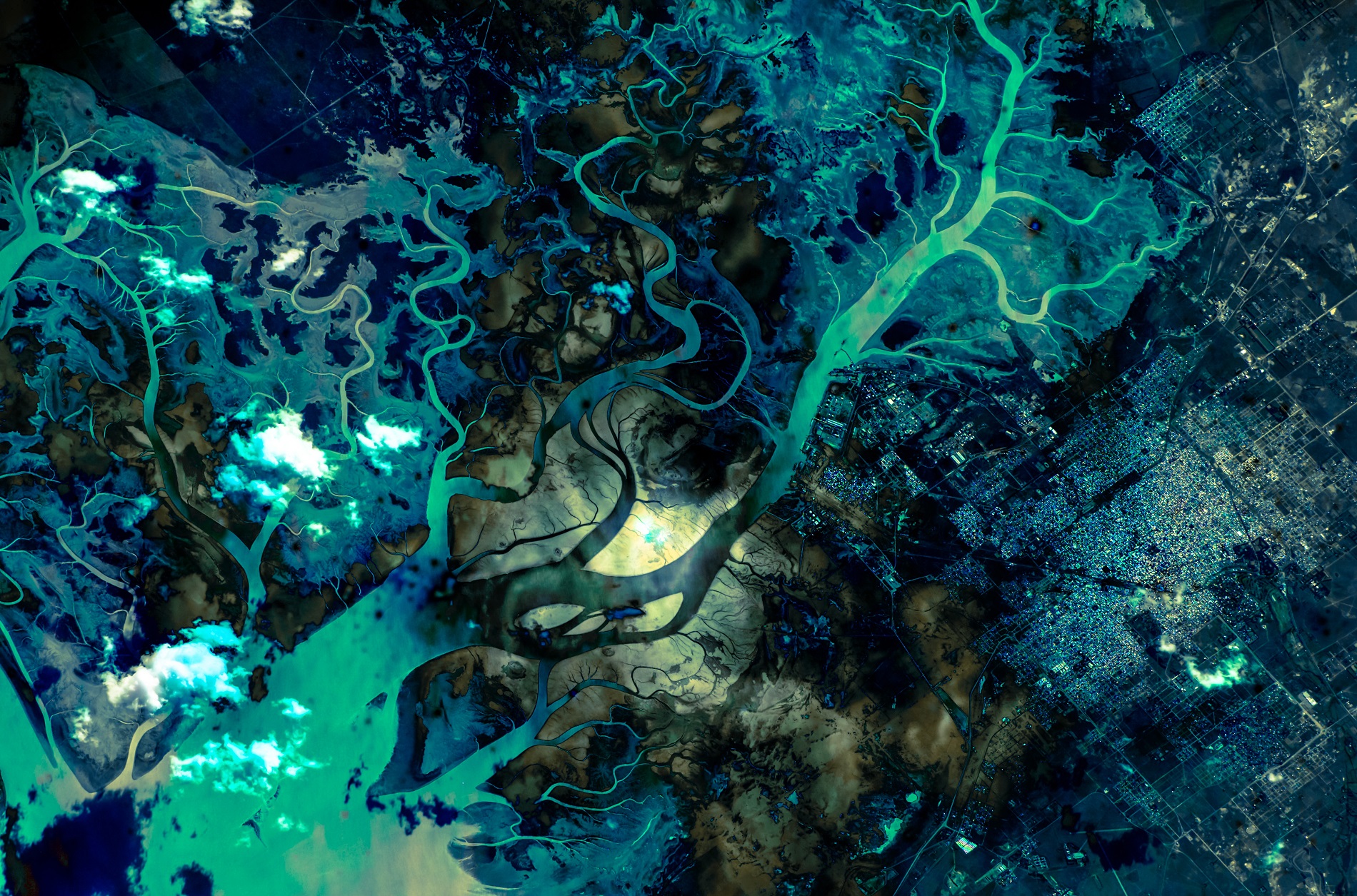

The modern economy is only now chasing what maritime societies mastered long ago: resource efficiency, circular design and resilience tuned to living systems. Yet the populations closest to these systems remain excluded from value chains. Ama divers in Japan, a group of traditional free-divers who have been working coastal waters for more than 2,000 years, detect changes in ocean temperature and species behaviour years before satellite data confirms the shifts. They are frontline monitoring systems for marine health, yet their observations rarely inform the research that receives funding. We spend billions addressing challenges that maritime communities have already solved: mangrove-based coastal protection, polyculture aquaculture eliminating disease without antibiotics, coral restoration, natural fibre composites from marine organisms, distributed water governance in coastal systems and architecture requiring no external energy inputs. What was once foundational knowledge is now repackaged and resold at a premium.

The scourge of untreated wastewater

The scourge of untreated wastewater Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution

Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC

Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC