Collaboration has always been one of the major strengths of ocean science. When you’re at sea on a research expedition, you work as a team, with different scientists working to address pieces of a bigger story. This attitude is built into the community, and we see it in Ocean Decade initiatives like the Ocean Conference. There’s a real willingness to collaborate, integrate, and be a community. I think this community is also really proactive in addressing autonomy, AI and machine learning, because we work in very difficult places, and autonomy allows us to do more. Overall, it’s a very creative, innovative community.

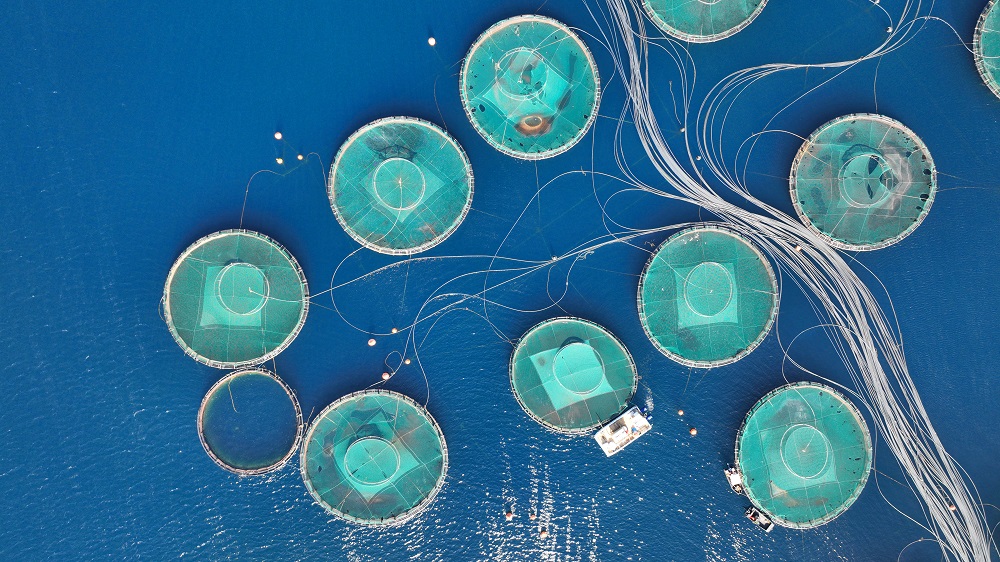

Regarding funding, the investment in Sustainable Development Goal 14 is way below everything else. It’s always been a struggle getting funding, and looking at the current geopolitical situation, it’s going to get even more difficult. Some of the community’s ambition is hampered by a lack of resources. Weather forecasting, which is recognised as an activity for the international public good, is effectively funded by governments coming together to commit to delivering an observing system, but there’s no similar funding ambition for ocean health observation. At the moment, it’s left to the overstretched, under-resourced science community. This comes right back to our initial conversation around recognising the ocean’s value. We see how much fish we can get out of it, or how we can use it to transport goods around, but those metrics don’t reflect the ocean’s true value.

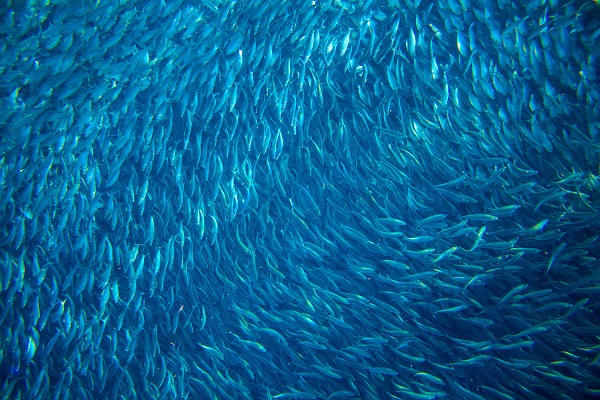

Another issue is the fact that the vast majority of the ocean sits outside anyone’s sole ownership. This could be a strength if we had a mechanism operating like the Antarctic Treaty, which protects Antarctica by saying it belongs to all of us, therefore it belongs to none of us. But we don’t have the same level of protection for the open ocean. Everyone’s staking their claims for mineral deposits, or massive factory ships are sucking up huge shoals of fish because it’s in no one’s territorial water, so it’s all fair game.

The scourge of untreated wastewater

The scourge of untreated wastewater Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution

Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC

Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC