After tragedies like the thalidomide scandal and the Bhopal chemical disaster brought awareness to the links between chemicals and chronic health issues, birth defects and cancer, among other afflictions, concern about chemical dangers went mainstream. This spurred legislation like the 1976 US Toxic Substances Control Act (TOSCA), which intended to prevent disease by requiring toxicity testing of new chemicals before market entry as well as existing high-risk chemicals. Yet industry pushback quickly undermined its effectiveness.

Within a year, the US Environmental Protection Agency grandfathered in around 62,000 chemicals already on the market as ‘safe’. “There was a certain momentum built into the chemical industry, where the government looked favourably upon it, didn’t want to criticise it and continued to support it for a long time,” says Dr Phil Landrigan, professor of biology and director of the Global Public Health Program and Global Observatory on Planetary Health at Boston College. Only five chemicals have been removed under TOSCA, despite tens of thousands more entering markets, setting a tone of lax regulation that persists today despite mounting evidence of hazards.

European regulation is similarly constrained. The EU’s chemical legislation, known as REACH, aims to register and restrict substances of very high concern, including those that are carcinogenic, mutagenic and reprotoxic and those that are persistent, bioaccumulative and toxic. “On paper, REACH is a lot stronger than TOSCA, but in practice, it’s not a whole lot different,” says Dr Landrigan. “It has been a bit more effective at getting chemicals off the market, but it still relies very heavily, for example, on testing undertaken by the industries themselves, which creates an inherent conflict of interest.”

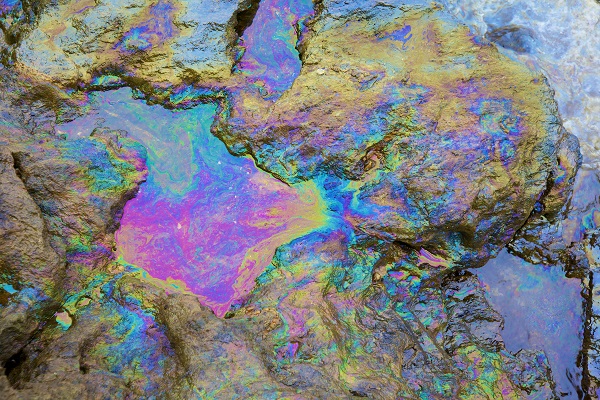

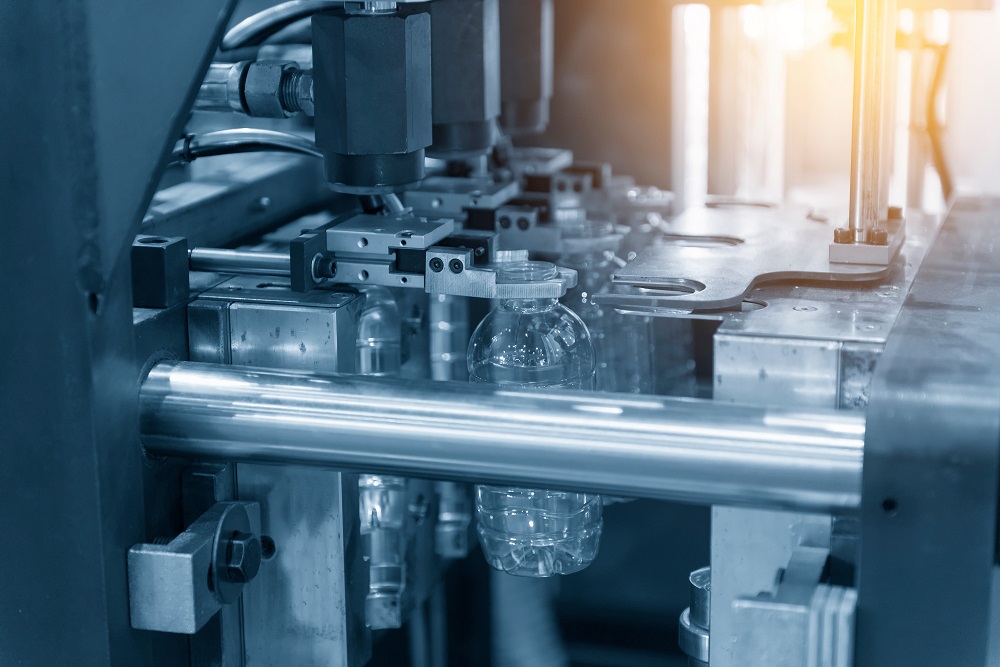

As a result of lags in regulation, there are many chemicals in use with unknown health impacts. The number of chemicals in plastics is now estimated to be around 16,000, most of which have never been tested for toxicity, meaning that we have not measured their true cost. We know that two million lives were lost to exposure to selected chemicals in 2021. However, data are only available for a certain number of chemicals due to gaps in scientific evidence, so, in reality, these numbers could be far higher.

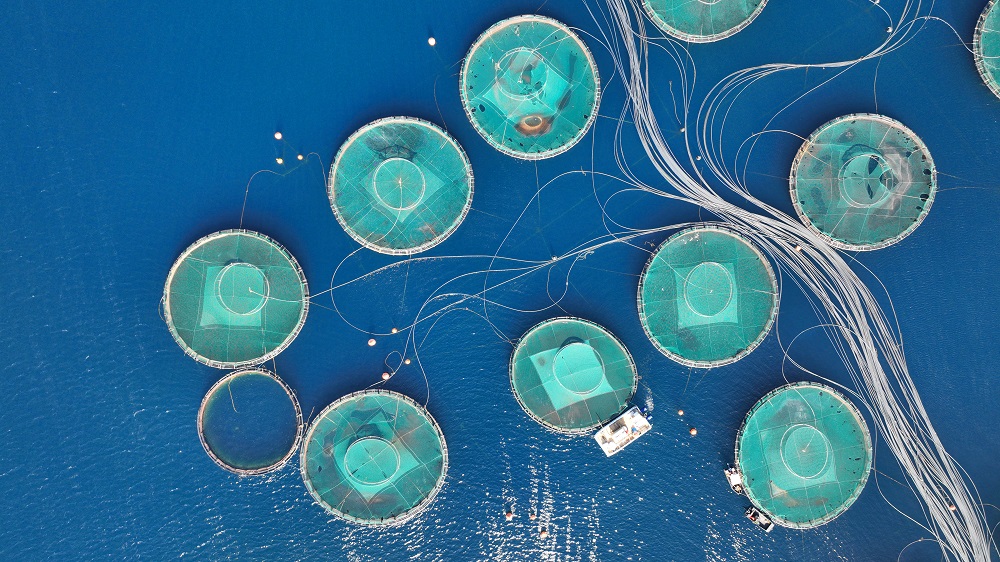

The scourge of untreated wastewater

The scourge of untreated wastewater Slowing

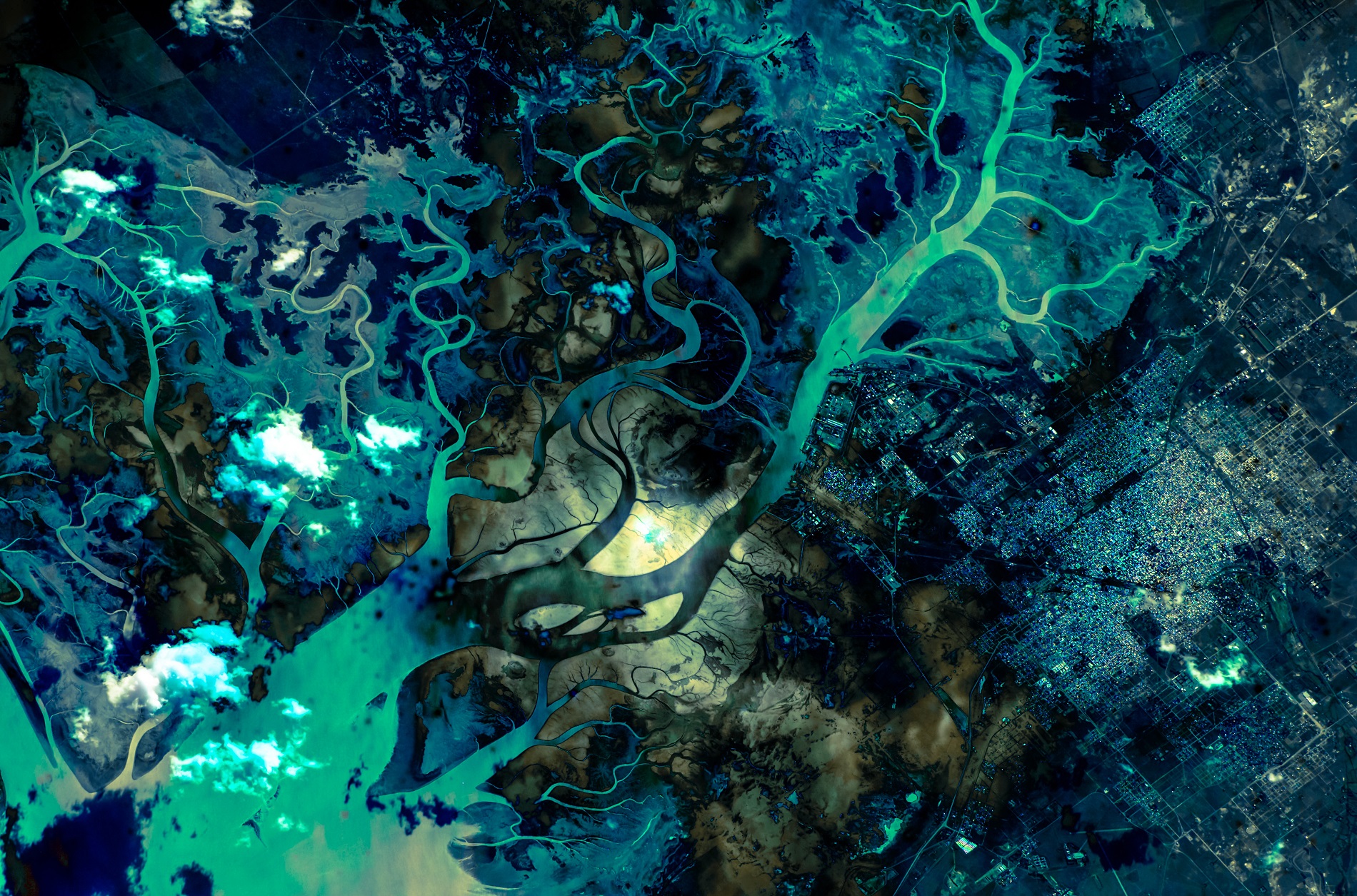

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution

Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC

Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC