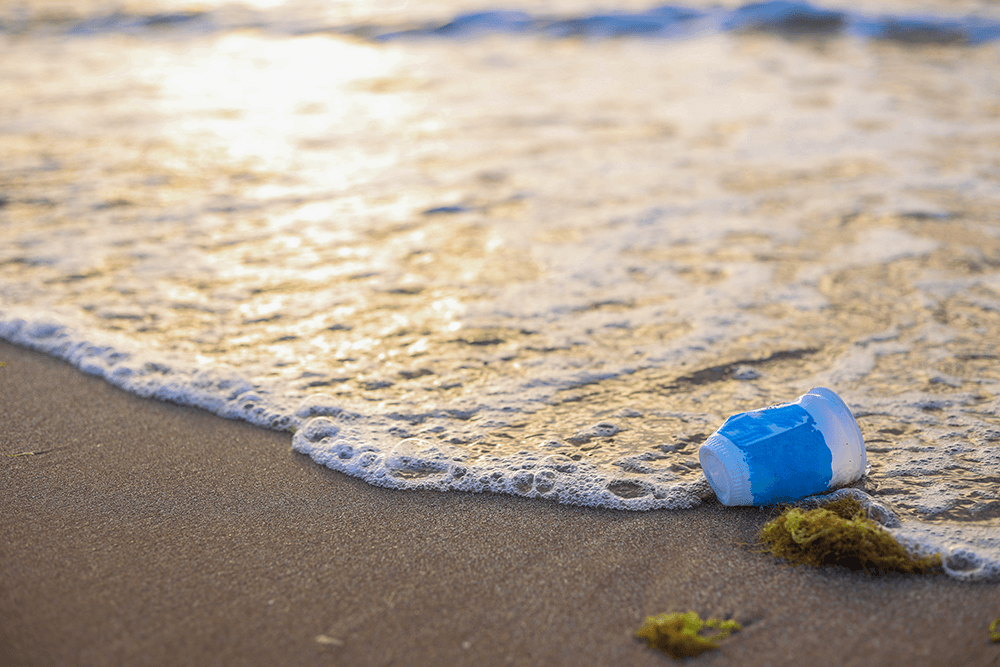

In December, the first of five Intergovernmental Negotiations Committee (INC) meetings took place in Uruguay, with over 2,000 delegates formulating a work plan for the Global Plastics Treaty. The agreement, scheduled to be signed by the end of 2024, is the most ambitious environmental deal since the Paris accord of 2015.

Delegates gathered for a multi-stakeholder forum, regional consultations and substantive discussions. The so-called INC-1 gathering, building on the landmark UNEA Resolution from early 2022 to forge a plastics treaty, was procedural. However, it attracted significant interest and media coverage, and the secretariat was tasked with developing a work plan for INC-2, set for May 22nd 2023 in Paris. The sessions built on steps taken last year in defining the treaty’s definitions, core elements, interactions with other treaties, potential structures and legal approaches (a helpful set of briefs is available here).

The meeting brought its share of challenges. In the lead up, there was confusion about the format and representations. The delivery of 170 country opening statements was inevitably lengthy, and there were reportedly tensions between Russian and Ukrainian delegates, which distracted from the negotiations at hand. But the gathering did deliver progress. David Ford, founder of the Ocean Plastics Leadership Network (OPLN), likens the deal to a huge boulder that “everyone is pushing from different directions, but that we are finally starting to get moving”.

Two work streams have been identified. The first covers substantive elements—objectives, scope, core obligations and control measures—and the second is on the means of implementation and financing, institutional arrangements, assessment of progress and stakeholder engagement. This month’s Back to Blue feature outlines key trends from the talks:

Getting the structure right

INC-1 prompted substantive conversations on the scope, objectives and structure of the treaty. The options ranged from a framework agreement such as the Paris deal, in which individual countries set measurable goals, to a specific convention that includes all provisions, such as the Minamata Convention on Mercury or the Montreal Protocol.

There are divisions on whether goals should be global and mandatory or voluntary and country-led. With plastic pollution set to increase, measures that address the whole life cycle of plastic, from production and consumption to waste management, are needed. There will be an obligation for countries to produce some kind of national action plans and mechanism for reporting and assessing progress against the objectives of the treaty. International-level measures will require discussions on issues like harmonising standards, for instance, to regulate problematic or unnecessary plastic products and addressing sustainable levels of plastic production and consumption. Among those present, Greenpeace does not want a Paris-style approach, calling for “universal, binding rules for all countries who chose to ratify the treaty, instead of voluntary national commitments” A top-down agreement would have internationally accepted legally binding guidelines, create lower compliance costs for business and drive economies of scale in the types of solutions needed to address plastic pollution in a systematic way.

High and low ambition countries: There are varied levels of ambition. From a governmental standpoint, experts credit the efforts of Rwanda, Norway, Switzerland, the UK, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Peru and the African group of nations, who are all calling for a global approach (a full list of countries in the High Ambition Coalition, calling for measures such as production curbs and a phase-out of certain plastic products and chemical additives, can be found here). The US, Saudi Arabia and many Asian countries, by contrast, are pushing for a bottom-up approach, similar to the Paris agreement, in which countries voluntarily create their own national action plans. However, by the end of the meetings, the US was reportedly shifting to a hybrid position and showing openness to some top-down elements.

An evolving narrative: The mandate obtained from the UN Environmental Assembly (UNEA) was top-line, and one successful outcome of discussions at INC-1 was to ensure the plastics agenda encompasses all key social, economic and technical dimensions. This includes a stronger focus on the human health and human rights implications of plastic pollution including for children and young people, pregnant women, and workers with unique exposures. On the technical and scientific level, there were more informed discussions about the chemical and toxicity dimensions of plastics. And, to this end, INC-1 brought a soft launch of a Scientists Network for an Effective Plastics Treaty, which is engaging with member states and the UN Environment Programme UNEP to ensure that robust, impartial science informs the treaty process. The negotiations included a strong presence from the Global South and often marginalised groups, including the waste-picker community, which is calling for their interests to be included in a just transition, with universal social protections and practical steps to realising these in the supply chain. A civil society coalition with over 100 members has also formed, including those living close to petrochemical facilities, indigenous people and non-government organisations (NGOs).

Industry split: One dynamic of the negotiations is division within the private sector on the right approach. Some consumer goods companies have adopted high ambition positions, seeking a more prescriptive treaty and even phasing out virgin plastics—approaches that are close or indistinguishable from activists and NGOs. A Business Coalition for a Global Plastics Treaty led by World Wildlife Fund and the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, includes some of the biggest consumer packaged companies in the world, such as Nestlé, Unilever, Coca-Cola, Pepsi and Mars.

Some business voices argue that recycling cannot solve the crisis and call for a clear set of targets and obligations to support progress on reducing plastic production and increasing the circular economy approach: circulating plastic items that cannot be eliminated and preventing and remediating hard-to-abate macro and micro plastic leakage into the environment, as well as addressing legacy waste. Upstream industry players such as the plastic-producer sector and petrochemicals companies are emphasising waste management and are resistant to production caps. There are also differences between the positions of the European plastics industry versus the US.

African perspectives: There was a strong African delegation at INC-1. Key views from stakeholders included the need to ensure that the treaty provides adequate means for them to meet their obligations. This includes adequate and sustainable funding that is readily accessible, including the establishment of a dedicated multilateral fund; provision of effective channels for the transfer and deployment of technology and scientific research, as well as the implementation of capacity-building programmes in line with the principle of ‘common but differentiated’ responsibilities and national capabilities; and to ensure that the instrument eliminates harmful chemicals and plastics production while promoting reusing, recycling and recovering. Ghana advocated a provision that addresses the problem of legacy clusters, calling for a legacy fund to ensure generous contributions.

Rules of procedure

There are issues with the rules of procedure, including those related to voting. Some countries prefer to not have voting within the context of the treaty, meaning everything is consensus-based, whereas others argue for a default to having a vote on an issue. Also unresolved is the bureau of countries guiding the content of the negotiations. At the moment this cohort includes Senegal, Rwanda, Antigua and Barbuda, representing the small island developing states. Added to this are Japan, Jordan, Sweden, the US, Peru, which is the chair, and Ecuador, which will be the second chair. There are two bureau spots from the Eastern European group that have not been confirmed. There was only one delegate funded per developing country, which proved an issue, as they could not attend more than one simultaneously running discussion. Experts also pointed out that there is little time between INC-1 and INC-2 in treaty negotiation terms, which could prove an obstacle for stakeholders being able to adequately digest the information and translating it into concrete positions.

According to UNEP, mission-critical issues for the treaty’s design, in terms of viability, include:

- Failure to include controls on virgin plastic polymer production

- Lack of monitoring and reporting obligations

- Inadequate and unstable funding

- Lack of transparency and restrictions on the chemicals used in plastic products

- Linear-economy conceptualisation of plastics.

- Replicating the failings of the Paris Agreement

It remains to be seen whether the delegates can steer the next phase of negotiations with the right blend of speed and care.

As well as the sources listed, this article is based on insights shared in an OPLN webinar held in December and Back to Blue interviews with Mr Ford, Marta Lopata (partner, OPLN) and Yoni Shiran (partner, SYSTEMiQ). We thank them for their insights and support.

THANK YOU

Thank you for your interest in Back to Blue, please feel free to explore our content.

CONTACT THE BACK TO BLUE TEAM

If you would like to co-design the Back to Blue roadmap or have feedback on content, events, editorial or media-related feedback, please fill out the form below. Thank you.

World Ocean Summit & Expo

2025

World Ocean Summit & Expo

2025 UNOC

UNOC Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution

Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC

Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC Dead zones: how chemical pollution is suffocating

the sea

Dead zones: how chemical pollution is suffocating

the sea