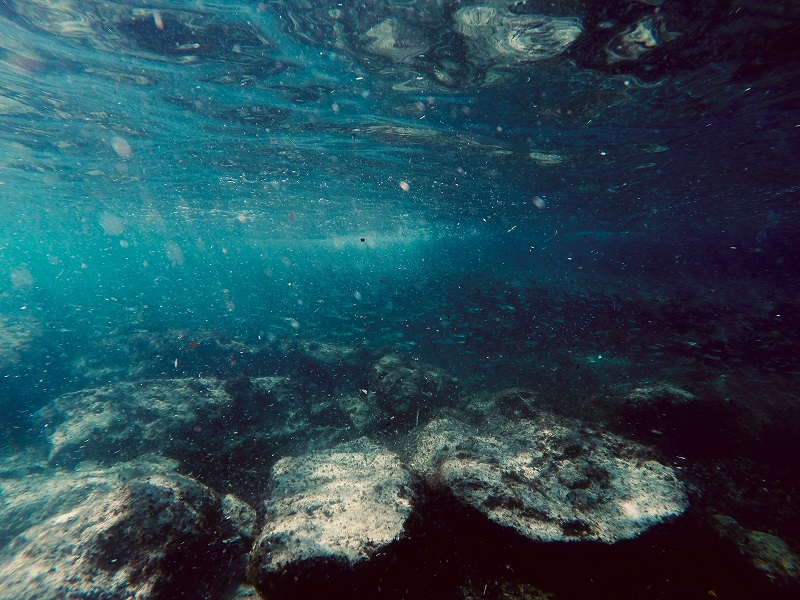

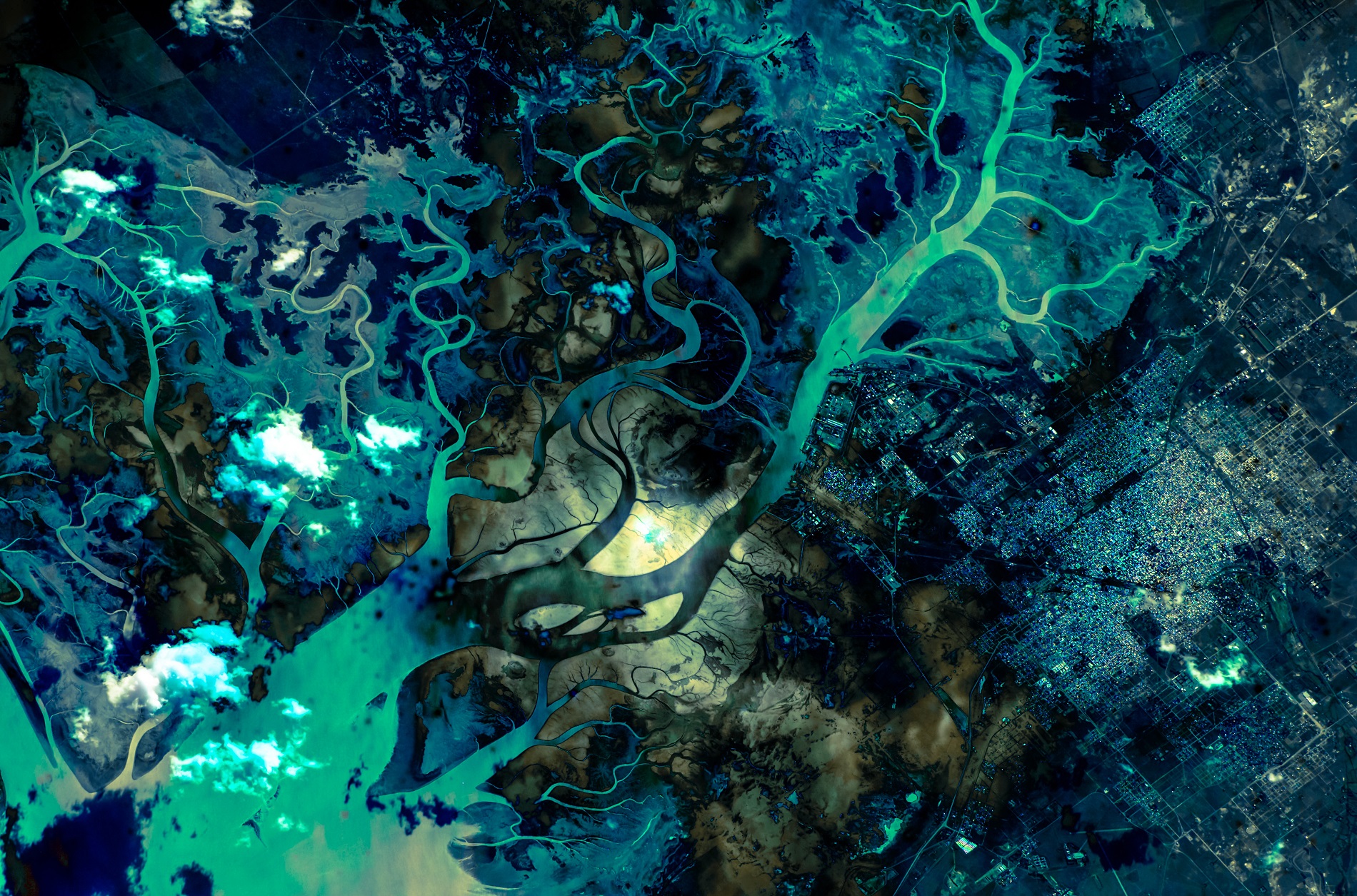

One of the most insidious forms of construction waste is microplastics. Polymers, which are used as a binding agent, make up 37% of paint, on average. When dry, they produce what is essentially a plastic film, which discharges microplastics into the environment as it degrades. Paints are the world’s largest contributor to microplastics in the ocean, producing 1.9 million tonnes a year, of which architectural paints are the biggest portion. During painting, sanding and cleanup, particles slough off into the environment and migrate into the oceans if not properly contained.

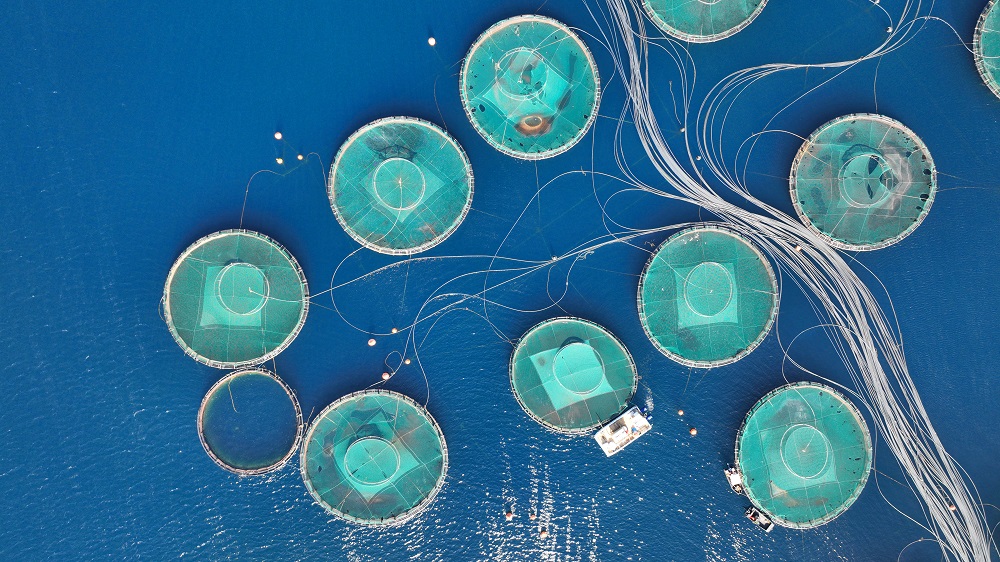

Aside from microplastics, many paints contain titanium dioxide, a white powder that gives paint its opacity. When large amounts of titanium dioxide reach the ocean, it causes an overload of nutrients in the water, triggering excessive algae growth and blooms that can harm ocean ecosystems and kill off native species. Some paints also contain per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), known as “forever chemicals”. One report found these substances are often excluded from a product’s ingredient list even when present. All of them can end up in the ocean when construction waste is poorly managed.

When paint brushes, tools and painters’ hands are washed, the wastewater flows into the sewage system, which is not equipped to deal with the potentially toxic contents of paint residue. Compounding the problem, some sewer overflow systems co-mingle stormwater and wastewater; when the stormwater capacity is exceeded, it is discharged into waterways without passing through the plant, even if it has been combined with commercial and industrial waste. “Wastewater treatment plants have limitations; they don’t just make waste magically disappear,” says Mr Crimston. “Everything that gets discharged into the sewer ends up in the environment in one way or another.”

The scourge of untreated wastewater

The scourge of untreated wastewater Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution

Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC

Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC