Cost and financial incentives are not the only obstacles to progress. The complexity of the chemical universe makes fertile ground for the selective, non-comparable reporting that furnishes the worst greenwashing practices. “Green chemistry means so many different things for different people and different companies, depending on how the company or the organisation is trying to implement these definitions,” says Dr Kleimark.

The carbon emissions produced by a shoe, a smartphone or a hamburger are becoming easier to quantify thanks to advances in data science and the simplicity of the end point: CO2. The sheer number of chemicals in existence make it hard, perhaps impossible, to quantify performance in a consistent, comparable way. Because of how many chemicals exist, companies can bend the story to their favour.

“They can say ‘we have phased out these kinds of chemicals because they are hazardous’, but they might use a lot of other hazardous chemicals which we don’t know about,” he observes. Some chemical processes are also trade secrets, so firms “don’t want to share what they are doing in order to achieve a better process. So overall, it’s much more problematic to have a metric for showing the change,” argues Dr Kleimark.

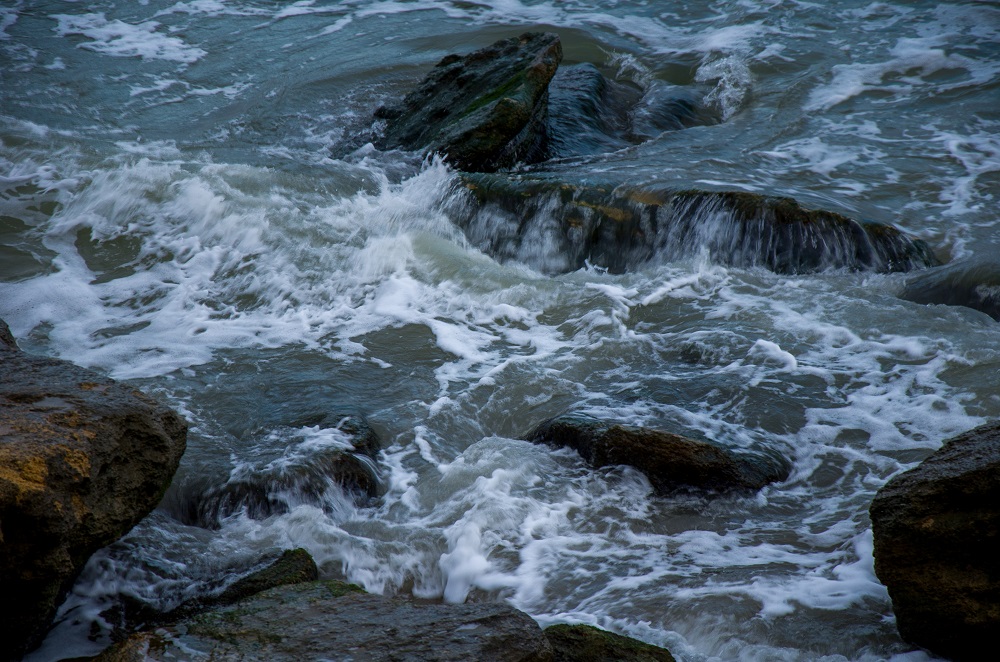

The scourge of untreated wastewater

The scourge of untreated wastewater Slowing

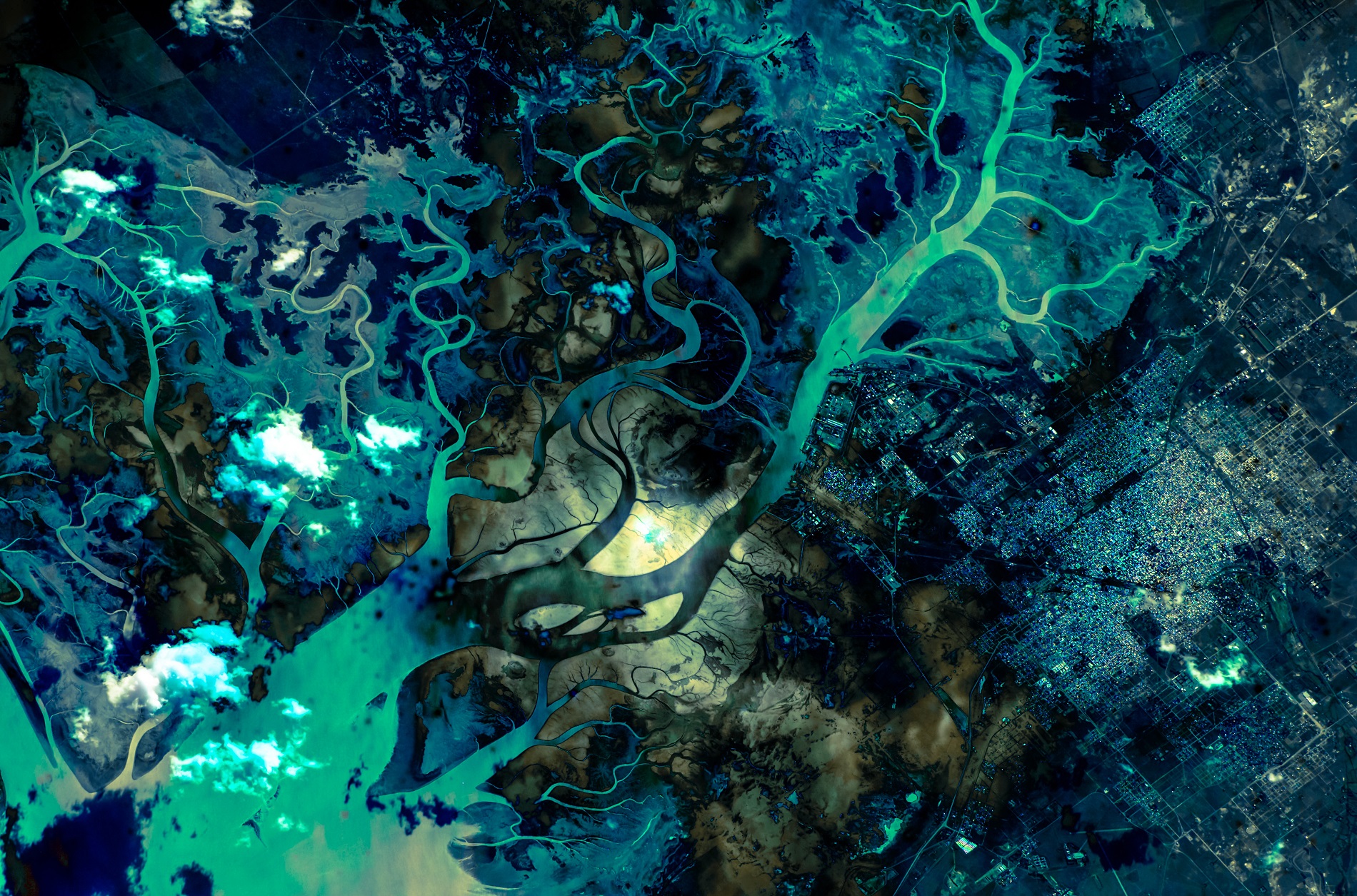

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution

Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC

Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC