Despite lengthy discussions, delegates at INC-3 were unable to agree on a mandate for intersessional work on technical and scientific issues ahead of INC-4. Ms Mahesh lamented the lack of progress, suggesting that it was derailed due to a lack of agreement among the countries. Dr Seay described this as discouraging, and he is pessimistic about any agreements being made in the short time frame given by the UN, which is the end of 2024. Pushback is coming from states that depend heavily on petroleum.

There is agreement that chemicals clearly proven to be toxic should not be used in plastic products. Ms Mahesh explained that these include chemicals like Bishenol A and heavy metals. Toxicity data, however, are not available for all chemicals, and there are numerous data gaps relating to the toxicity of plastic packaging-associated substances. “There are a lot of chemicals where we do not have concrete toxicity data. Those have to be defined in a specific way, and over time there needs to be more research to evaluate the impacts to know if they belong on the safe list of chemicals or to the toxic chemical list,” said Ms Mahesh. “These chemicals include endocrine-disrupting chemicals. Microplastics also need to be looked at as they are carriers of chemicals,” she further explained. She thinks that it is unfortunate that due to the lack of data on these chemicals, they may not be put in the banned or restricted list under the treaty.

In addition to the lack of an agreement, treaty discussions were bogged down on procedural issues, such as whether it would be ratified by two-thirds majority or consensus. Dr Seay thinks these are delay tactics, taking the focus off what the plastics industry will look like in the future.

But is a treaty the right way to go, and is there precedent for treaties shaping decisions in the chemicals industry? The US, for example, is not a signatory to the Basel convention and is yet to ratify any international efforts against plastic pollution. But Dr Seay thinks that, since plastics are a global marketplace, even if countries opt out of the treaty they are still doing business with countries that have ratified the treaty and will therefore need to follow the rules and regulations.

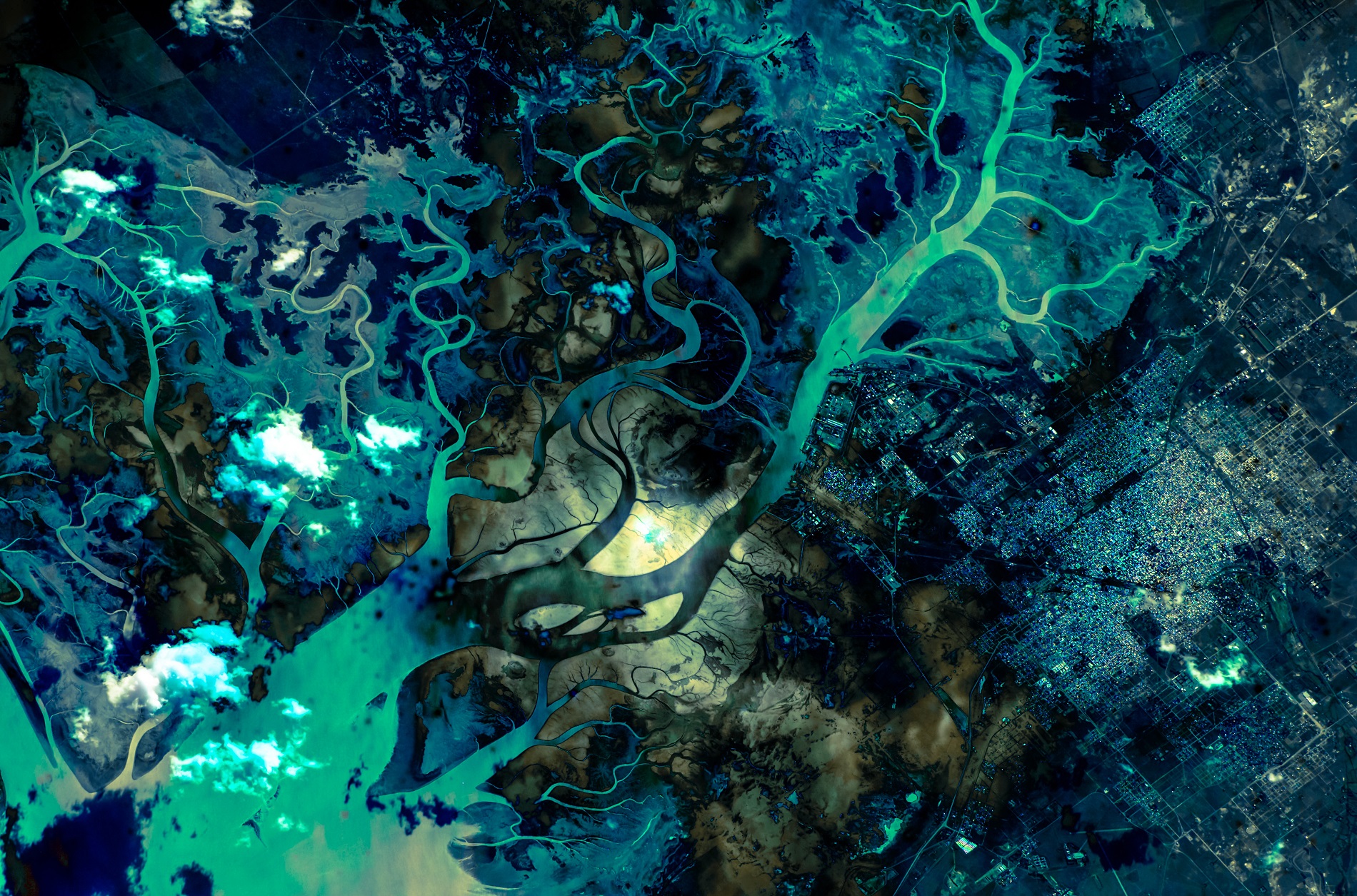

The scourge of untreated wastewater

The scourge of untreated wastewater Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution

Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC

Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC