Step one in applying an actuarial lens to climate is framing it as a risk-management problem: what do we want to avoid and what action do we need to take? In practical terms, that means setting a budget. In climate science, a carbon budget defines the maximum amount of carbon dioxide that can be emitted while keeping global warming below a chosen threshold, such as 1.5°C or 2°C. Defining legally binding temperature limits translates to budgets, which form an integral part of the Paris Agreement and UN Framework Convention on Climate Change negotiations.

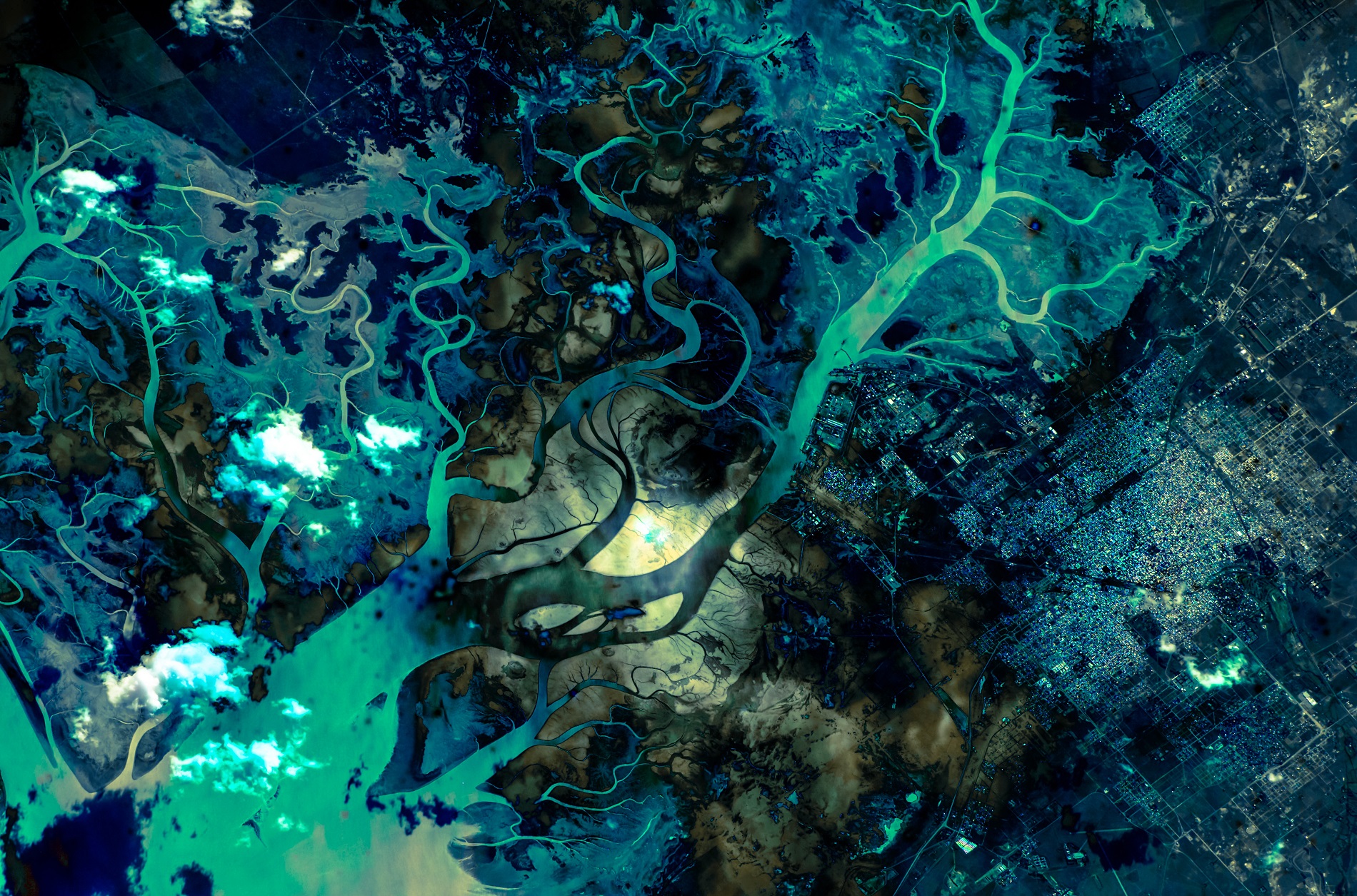

The planetary boundaries framework extends this “budget” approach beyond climate, applying it to other critical environmental limits, including ocean warming. Introduced in 2009 by an international team of researchers led by Professor Johan Rockström at Stockholm University, the framework identifies nine key Earth system processes that support a stable planet: climate change, ocean acidification, biodiversity loss, biogeochemical flows (of nitrogen and phosphorus, for example), land-system change, freshwater use, atmospheric aerosol loading, stratospheric ozone depletion and novel entities (such as plastics and chemical pollution). “Every planetary boundary, once quantified at the global level, translates into a finite resource budget,” says Professor Rockström. “These budgets serve as a benchmark for risk assessment.”

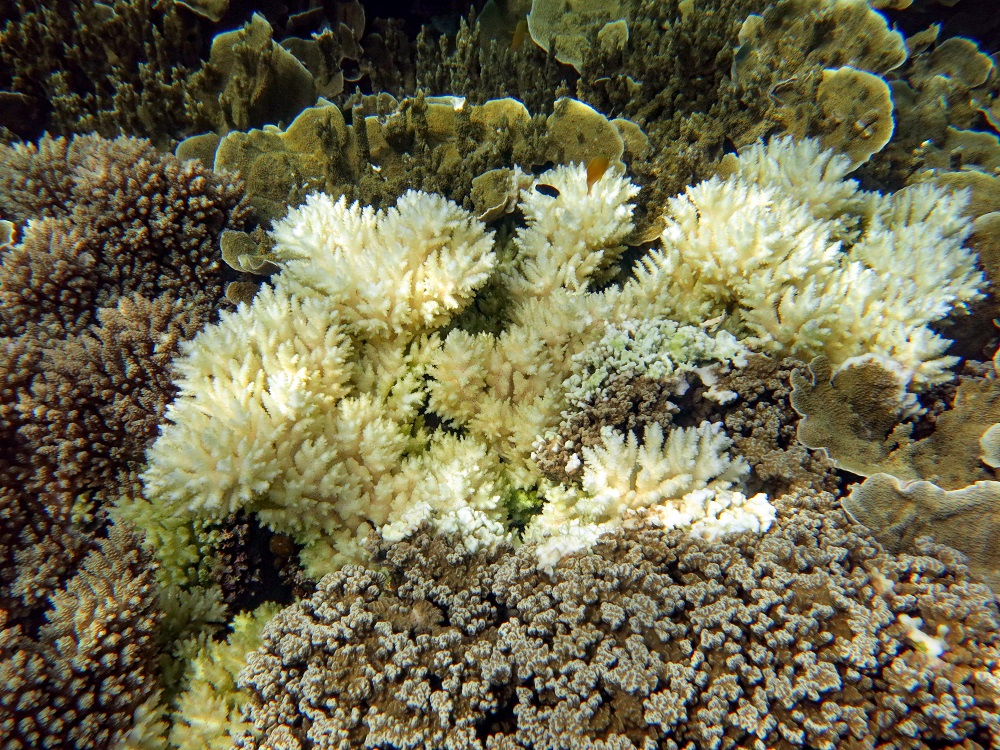

As of the latest assessment, in 2024, all boundaries except atmospheric aerosol loading, stratospheric ozone depletion and ocean acidification have been breached. This analysis placed ocean acidification just within the boundary, but the trajectory is worsening, and the planet as a whole is well outside the safe zone.

The scourge of untreated wastewater

The scourge of untreated wastewater Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution

Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC

Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC