Yet, there is also risk. Ocean scientists we spoke with told us they have not yet been consulted and it is not clear how or whether the scientific community will be given a voice in the treaty negotiations. Others expressed a worry that not enough is being done to prepare and inform UN member-state negotiators, many of whom have limited knowledge of the problem of plastic pollution and how to implement solutions. The worry? That developing country governments may vote for a lowest-common-denominator treaty for fear of being locked into expensive policies that they simply don’t have the finance or capacity to implement.

There is one more, somewhat prosaic, worry. The treaty is due to be settled by the end of 2024, giving negotiators a heroically optimistic two years to get the deal done. Yet three months in, there is growing frustration that key details of the negotiating process are still up in the air (or, at the very least, not well understood).

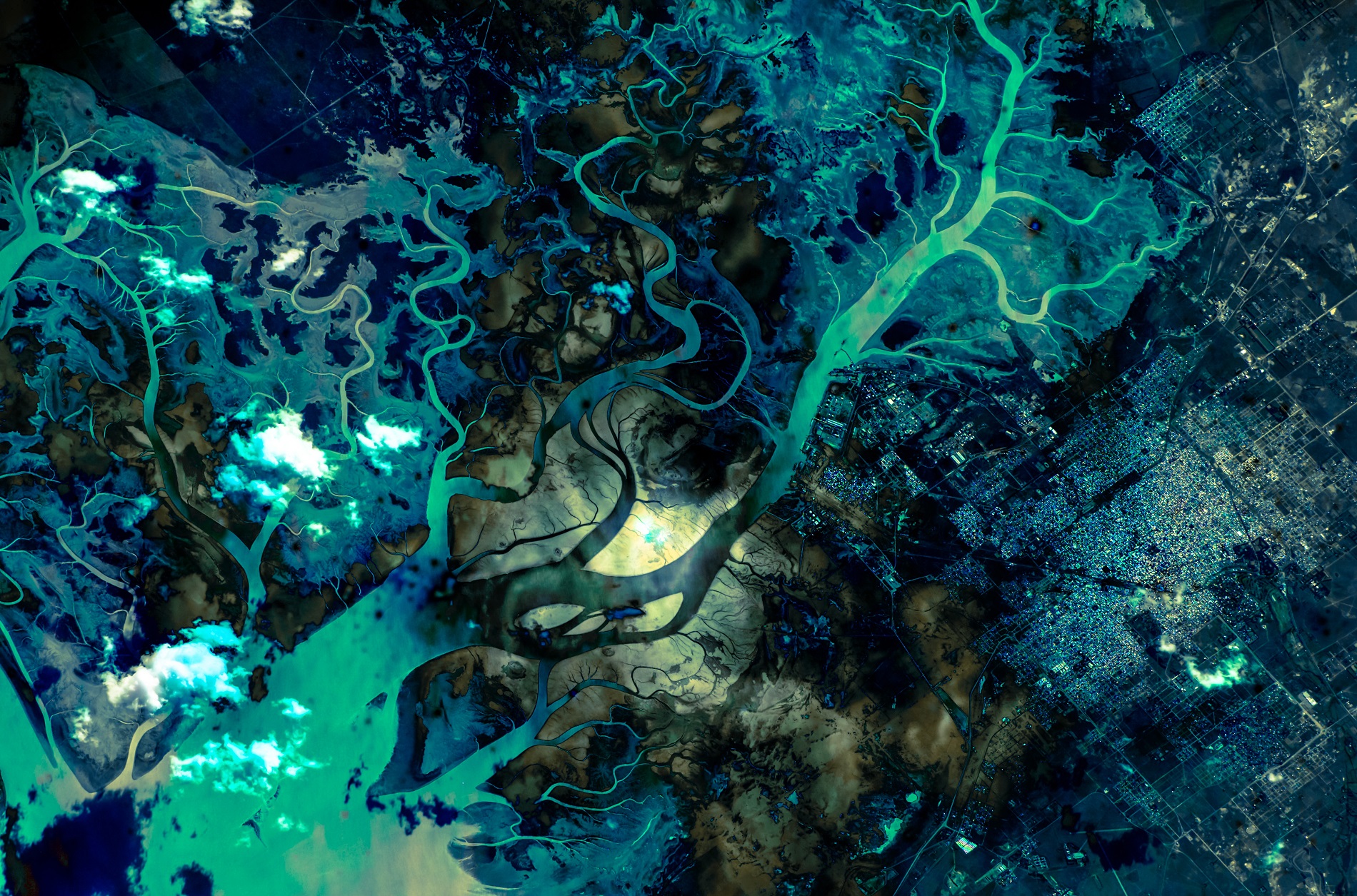

The scourge of untreated wastewater

The scourge of untreated wastewater Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution

Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC

Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC