In the tropical heart of Kerala, where the Arabian Sea meets the backwaters, and monsoon rains both nourish and overwhelm, Kochi is a place of resilience and renewal.

Formerly a bustling hub of maritime culture, the city was sustained by its intricate network of canals. Among them, the 10-km Thevara–Perandoor (TP) Canal, served as a vital waterway linking inland towns to Kochi’s port.

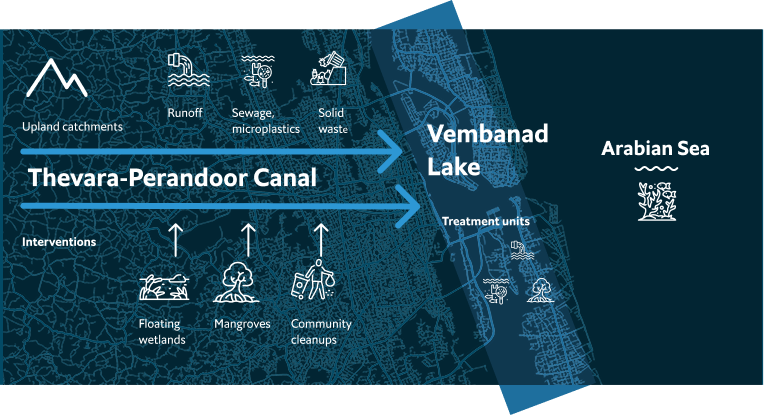

Over time, however, unchecked urbanisation and neglect have choked the TP Canal. Once thriving, it has become an outlet for waste and runoff, sending pollutants first into Vembanad Lake, India’s longest freshwater lake and a wetland of global importance, and ultimately into the global ocean. Studies have found a high concentration of microplastics in the lake (ranging from 96-496 particles/sq metre), affecting fisheries, migratory birds and livelihoods.

How the Thevara–Perandoor Canal Restoration Programme aims to restore Kochi’s canals.

Natural disaster a wake-up call

Devastating floods in 2018 were a turning point. With 2,411 mm of rainfall during the south-west monsoon season (June 1st to August 28th 2018), compared with a typical 1,770 mm, Kerala’s “disaster of the century” exposed the cost of damaged natural infrastructure. Hundreds of lives were lost and the state was forced to seek 400bn rupees (US$4.50bn) in aid. The floods made it clear that restoring Kochi’s waterways was not only an environmental imperative but also an economic and social one.

In response, Kochi launched an ambitious plan to revive its canal systems, linking local action to global ocean resilience. The Integrated Urban Regeneration and Water Transport System (IURWTS) project, launched in 2019, seeks to restore five major canals, reduce flooding and create a water-based public transport system. The TP canal is its centrepiece, linking environmental management with mobility, heritage and climate resilience. The TP Canal Restoration Programme unites the Kochi Municipal Corporation (KMC), the KMC’s Centre for Heritage, Environment and Development (C‑HED) and the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) in a collaborative effort to reclaim the city’s water heritage.

Monsoonal rain in Kerala.

Established in 2002, C‑HED acts as KMC’s research and development arm, helping to bridge heritage, planning and environmental governance. Its mandate ensures that restoration is not just technical but also cultural: reconnecting Kochi’s residents to the waterways that once defined their city.

UNEP’s involvement brings global expertise, connecting Kochi to peer cities such as Barranquilla in Colombia and Kisumu in Kenya, where restoration of degraded waterways is improving both biodiversity and quality of life. The revival in Barranquilla of the polluted León Creek and the restoration in Kisumu of the Auji River offer blueprints for Kochi’s own journey, showing how hybrid infrastructure can combine natural buffers with engineered systems to enhance resilience.

“The Kochi canal rejuvenation programme aims to transform the TP Canal into a clean, flowing and multi-functional waterway,” says Mirey Atallah, chief of the Adaptation and Resilience Branch at UNEP. Desilting, pollution control and nature-based solutions will help to restore oxygen balance and aquatic health, she explains.

Towards an ocean free from the harmful impacts of pollution

Kochi’s canal revival fits within broader global efforts to curb ocean pollution and promote sustainable coastal development. Back to Blue, an initiative of Economist Impact and The Nippon Foundation, has worked with experts from science, industry, policy, finance and the UN to develop solutions to address ocean pollution. A Global Ocean Free from the Harmful Impacts of Pollution: Roadmap for Action offers a framework to catalyse collective action.

In response, the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO (UNESCO-IOC) and UNEP are proposing a multi-decade partnership as part of the UN Ocean Decade (2021-30). Their vision: to build a strong evidence base, close data gaps and spur decisive public- and private-sector action by 2050.

The TP Canal project illustrates how these goals can be met locally. By improving water quality, intercepting waste and reducing microplastic leakage into the Arabian Sea, the project directly contributes to the vision of a pollution-free ocean by 2050. The integration of local monitoring data into UNEP’s global freshwater frameworks helps to connect community-scale outcomes to global indicators. “By engaging municipal agencies, academic institutions and communities, Kochi strives for long-term maintenance and behavioural change. The approach is highly scalable for other coastal and climate-vulnerable cities, as its modular interventions such as floating wetlands, decentralised treatment systems and community-led monitoring can be adapted to varying contexts worldwide,” says Ms Atallah.

Kochi city, Kerala.

Fishing in Kerala

Global frameworks, local partnerships

Kochi’s restoration journey is part of a growing global movement. Under UNEP’s Generation Restoration Cities initiative, launched as part of the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration (2021–30), Kochi is one of 19 cities receiving support to integrate nature-based solutions into urban planning. The initiative aligns local restoration with global frameworks such as the Paris Agreement and the Global Biodiversity Framework.

Kochi’s inclusion reflects Kerala’s broader leadership in sustainability. The state ranks among India’s top performers in the national Sustainable Development Goals index, excelling in areas such as clean energy, education and zero hunger.

Kochi’s metro glides through a landscape that blends industry and greenery.

By widening choke points, creating natural stormwater channels and establishing riparian buffers, the project aims to mitigate flood risks while re-establishing the canal’s ecological and navigational functions, explains Ms Atallah.

“Key milestones include the completion of the preliminary phase, which involved an end-to-end reconnaissance of the canal, stakeholder consultations led by the mayor, baseline environmental assessments and community engagement programmes involving over 400 students from 55 schools,” says Ms Atallah.

This type of project can yield both environmental and economic benefits. A 2024 study by the International Institute for Sustainable Development found that investment in Kochi’s canal restoration yields benefits extending across health, flood protection, transport efficiency and tourism. A 2021 study by the Cochin University of Science and Technology found Kochi’s mangroves sequester an average of 2.95 tonnes of carbon per hectare annually, highlighting their climate value. Restoring them is not just about greening the canal’s edges, but also about reinforcing the city’s natural resilience against sea-level rise and storm surges. The findings of both studies underscore that environmental restoration, when done strategically, can be among the highest-yielding forms of public investment.

Reviving the canal: blending nature and technology

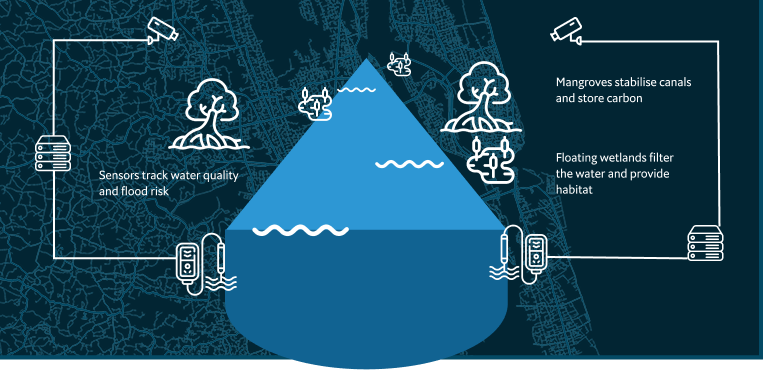

The Kochi canal project integrates ecological restoration, engineering innovation and smart data systems. Dredging removes accumulated sediment, while decentralised treatment units intercept sewage and solid waste before it enters the canal. Floating wetlands, which are artificial rafts planted with native species, absorb pollutants and provide habitat for aquatic life. Mangrove replanting stabilises the banks, stores carbon and supports biodiversity.

“Innovative green-grey infrastructure, such as bio-engineered canal banks, floating wetlands and decentralised sewage treatment units, is planned to enhance resilience and biodiversity in the long term,” says Ms Atallah.

Commuters travel by boat on Kerala’s canals.

The programme also deploys tools that create detailed 3D land maps and analyse how the landscape appears and changes, such as Digital Elevation Models (DEMs), LiDAR mapping, and GIS-based spatial analysis. These tools help to identify flood-prone zones and pollution hotspots, Ms Atallah explains. CCTV and smart sensors track waste dumping and monitor water quality in real time, while community-based teams support on-ground maintenance. These technologies turn Kochi’s restoration into a living laboratory for data-driven urban sustainability.

By mid-2024, dredging and desilting had already improved water flow in several sections that had earlier shown high phosphorus levels harming fish and plants. Waste barriers, signage and awareness campaigns were launched, and school-based initiatives encouraged students to treat the canal as a shared treasure. Early gains demonstrate the multiplier effects of combining technology, community action and ecological insight.

Blending nature and technology: Anatomy of the hybrid canal

Community at the heart

Critically, the project is owned by the people it serves. Community engagement is woven into every phase, from design and mapping to monitoring and maintenance. Residents participate in “mapathons” to chart pollution sources and green spaces; school students join competitions to design floating wetlands; and photo exhibitions contrast the canal’s past and present, inspiring both nostalgia and action.

Fishing in Kerala.

Once restored, the canal banks will feature walkways, gardens and educational signage. Festivals, dances and boat parades will celebrate Kochi’s maritime identity, turning the canal into a cultural corridor that attracts residents and tourists alike. The project also links directly with the 37.16bn-rupee ($419m) IURWTS initiative to expand water taxis and ease road congestion.

Inclusivity is central. Slum dwellers and fisherwomen are involved through co-operatives and resettlement programmes, receiving training in mangrove care, waste management and environmental monitoring. “The project emphasises skill development … creating green jobs that strengthen local ownership and stewardship,” says Ms Atallah.

Looking ahead: a blueprint for coastal resilience

As restoration progresses, measurable indicators will track ecological, hydrological and social change and signal improved flood resilience, explains Ms Atallah. Reopened navigation channels and increased community participation will demonstrate the programme’s social reach, she says.

The initiative also supports Kerala’s shift towards low-emission transport, easing congestion on road corridors. “New jetties and multimodal hubs [will] create seamless links between water-based and land-based transport systems,” says Ms Atallah, promoting non-motorised transport and improving air quality. Early signs of success, such as visible water clarity, community pride and increased biodiversity, point to a sustainable model of urban regeneration.

As Kochi looks ahead, the restoration of the TP Canal will define the next chapter in the city’s renewal, proving that fixing a city’s waterways can deliver powerful benefits for people, nature and the economy. “The success of the Kochi canal rejuvenation programme extends beyond ecological restoration, providing tangible socioeconomic benefits to local communities. Improved water quality and restored aquatic habitats will revive traditional livelihoods, such as small-scale fishing and agriculture. Cleaner and navigable waterways will stimulate waterfront-based enterprises, including eco-tourism, cultural boat tours and local markets,” says Ms Atallah.

Small-scale aquaculture in Kerala.

In a world where many cities are losing their connection to nature, Kochi’s effort has the potential to stand out as a beacon of hope. “Other cities can learn from Kochi’s emphasis on participatory governance, transparent data-sharing and combining engineering with nature-based solutions,” Ms Atallah believes.

Once written off as a polluted relic, the TP Canal may yet emerge as a symbol of balance between human progress and natural systems. By the end of 2025, as full-scale restoration gets underway, Kochi will be one step closer to the vision of a city that thrives on its waterways—a city where water flows freely, nourishing both its ecosystems and its people.

By transforming neglected waterways into vibrant public spaces, Kochi is redefining what it means to live with water, Ms Atallah reflects. The canal’s restoration shows that sustainable development is not a distant ideal: it’s a daily practice that reconnects people, nature and prosperity.

A call to action: lessons for other coastal cities

EXPLORE MORE CONTENT ABOUT THE OCEAN

Back to Blue is an initiative of Economist Impact and The Nippon Foundation

Back to Blue explores evidence-based approaches and solutions to the pressing issues faced by the ocean, to restoring ocean health and promoting sustainability. Sign up to our monthly Back to Blue newsletter to keep updated with the latest news, research and events from Back to Blue and Economist Impact.

The Economist Group is a global organisation and operates a strict privacy policy around the world.

Please see our privacy policy here.

THANK YOU

Thank you for your interest in Back to Blue, please feel free to explore our content.

CONTACT THE BACK TO BLUE TEAM

If you would like to co-design the Back to Blue roadmap or have feedback on content, events, editorial or media-related feedback, please fill out the form below. Thank you.

The Economist Group is a global organisation and operates a strict privacy policy around the world.

Please see our privacy policy here.

The scourge of untreated wastewater

The scourge of untreated wastewater Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution

Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC

Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC