Attempts to reach a last-minute compromise in Geneva were ineffective. “Late in the negotiations, the chair tried presenting a text that met the demands of the like-minded countries, and they didn’t even accept that,” says Mr Azoulay. But the other side opposed this weakened draft too. It leaned heavily on voluntary national actions and did not include any measures to tackle plastic production, which was a non-starter for the HAC and their more than 30 allies supporting binding commitments across the plastics lifecycle. To some participants, this demonstrated a promising resolve. “In other negotiations, watered-down texts have often been rushed through at the final hour, when delegates are tired and eager to finish,” says Ms Vojdovic. “That didn’t happen here. Countries advocating for an ambitious treaty held the line and refused to accept a weak agreement.”

With science on their side, the ambitious countries refused to back down. They are determined to frame plastics as not merely as a waste management issue but a systemic threat across their life cycle. “The agreement that was on the table was not in alignment with science and evidence,” says Bethanie Carney Almroth, who is a professor of ecotoxicology and zoophysiology at the University of Gothenburg and co-lead of the Scientists’ Coalition for an Effective Plastics Treaty, which provided an essential scientific voice for the talks. “There are more papers being published and more data becoming available on the impacts of plastics at every stage; that’s why so many countries rejected a weak version of the treaty that excluded upstream measures.” The human health dimension, too, was increasingly recognised, as research increasingly links plastic exposure to disease and premature death, particularly among vulnerable populations. “This issue is gaining traction, and I heard more countries discussing it in Switzerland than ever before,” says Professor Carney Almroth. Over 120 countries supported adding a standalone article on human health to the treaty text.

The Scientific Coalition has been pivotal in pushing for a full life-cycle approach, highlighting both environmental and human health impacts. Yet the disconnect between evidence and politics remains glaring: the stronger the science, the weaker the text that emerges from negotiations. The broader scientific and civil society context underscores this asymmetry. Even as more evidence emerges, government funding is shifting away from sustainability and development priorities, leaving scientists from the US to Sweden struggling. “The same problems that existed in Busan are still present, but the geopolitical situation has only become more difficult,” says Professor Carney Almroth. “From a scientific perspective, we’ve seen major shifts in national funding initiatives, and cuts to development aid have had a huge impact.”

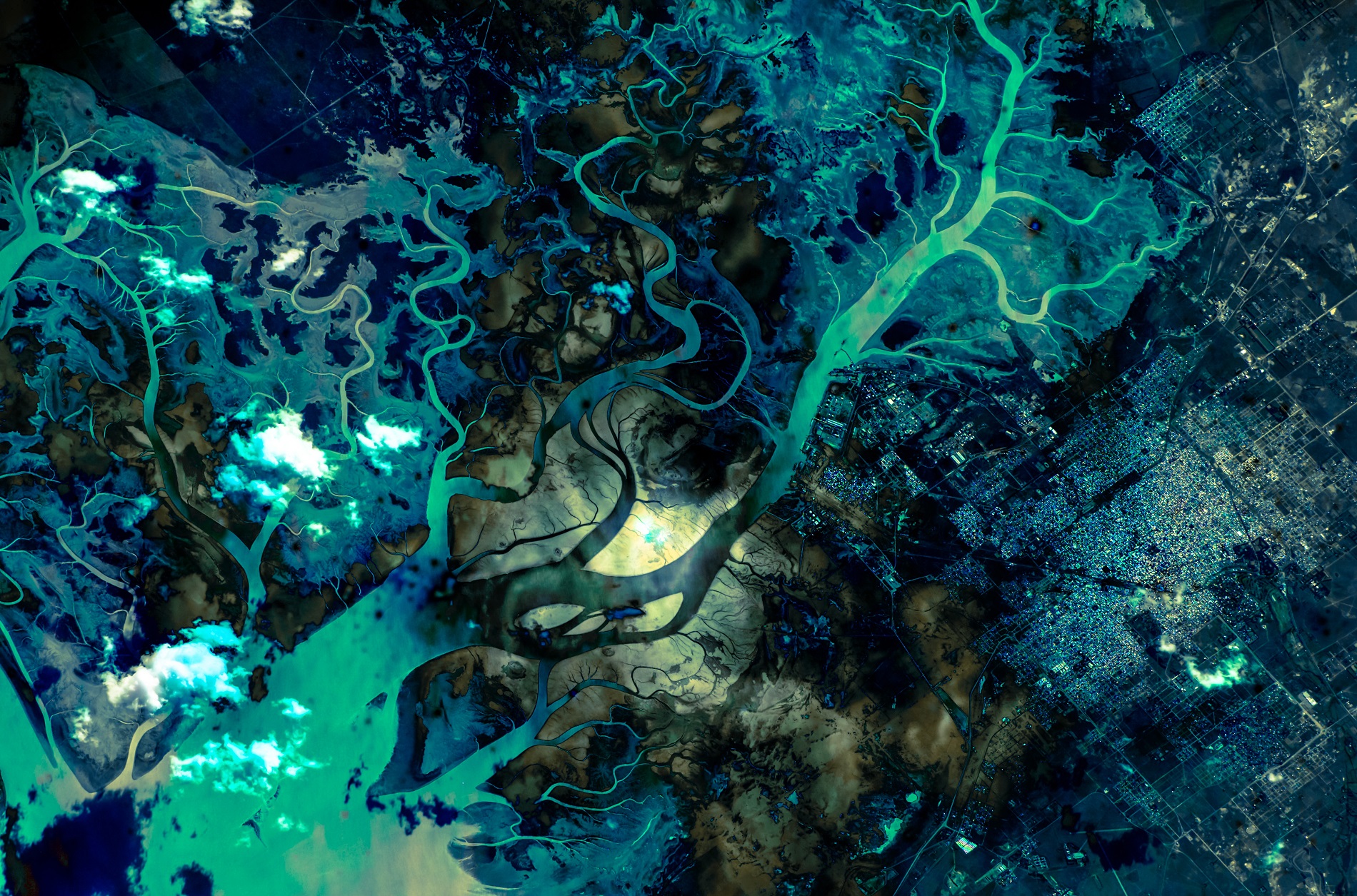

The scourge of untreated wastewater

The scourge of untreated wastewater Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution

Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC

Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC