Regardless of how negotiators define the plastics life cycle, transitioning to a circular economy will almost certainly be an important focus of the treaty. Few suggest that plastic can or should be phased out completely, meaning that reusing and recycling will feature prominently in any eventual outcome.

The ultimate solution must “respect the waste hierarchy and first design out the materials that we don’t need to use,” says Aidan Shilson-Thomas, climate research manager at ShareAction, an NGO that campaigns to raise standards for responsible investment across climate, environmental, health and workplace issues, and is closely focussed on the chemical sector. “To the greatest possible extent, any product that is made should be designed for reuse.”

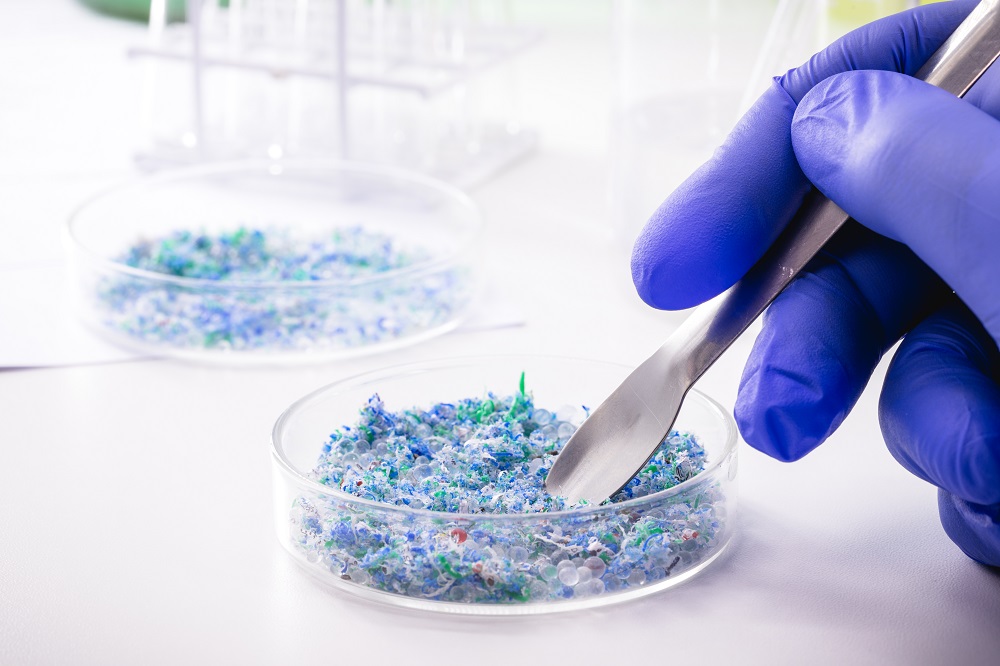

The shift to circularity will also, inevitably, require negotiators to consider the role of chemicals in plastic more carefully. The sheer number of chemicals currently used in plastic, as well as their transformation when exposed to the environment, presents a barrier to more widespread recycling. For example polyethylene terephthalate (PETE or PET) found in most plastics bottles and containers is recyclable and deemed safe whereas polystyrene (PS), used in foam packaging or disposable containers is difficult to recycle and “probably carcinogenic”. The first step, scientists say, is to reduce the number of chemicals used in plastic products. A global inventory of licensed plastic chemicals will also be important.

“Our vision of a circular economy for plastic presents challenges, but they are not insurmountable,” says Ms Dunlop. “Hazardous plastic chemicals, currently used in some plastics, run the risk of being included and even increased in recycled products that will either come into contact with humans or potentially leach out into the environment, which is why it’s critical to address toxicity higher up the chain.”

The scourge of untreated wastewater

The scourge of untreated wastewater Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution

Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC

Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC