While much innovation in uncrewed systems focuses on small coastal craft, the Tinmouths set a different course. “We thought it was more important to focus on the bigger vessels that are out at sea for longer, which people don’t want to crew and robots weren’t yet able to replace,” Neil explains. “That meant stability, so they can collect data on the high seas without having to return to port, and enabling other robotic systems to operate from the vessel itself.”

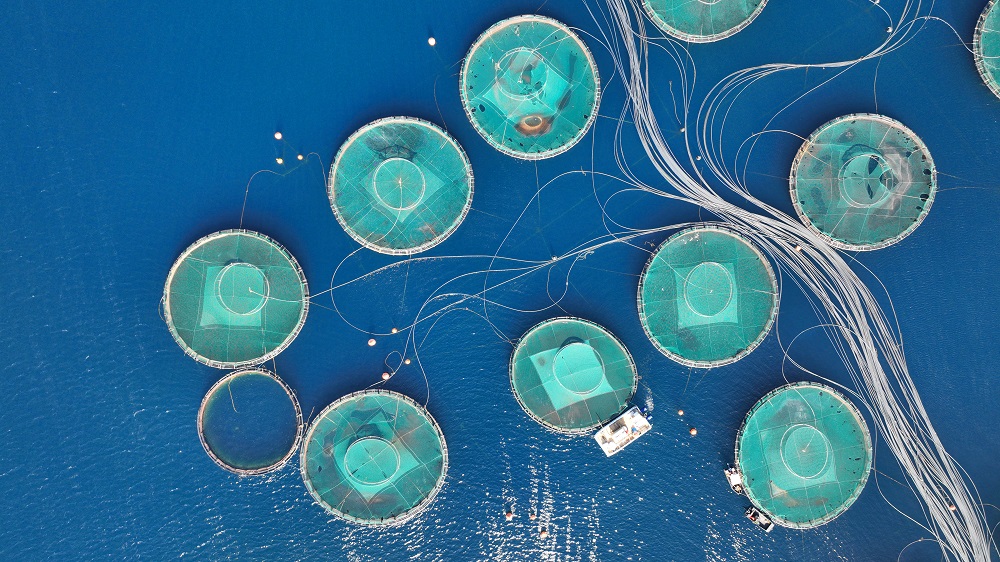

At the core of ACUA’s approach are “nested robotics”, or robots that deploy other robots. Their first class of vessel acts as a floating platform capable of launching aerial drones for wind turbine inspection, subsurface vehicles for fisheries monitoring or other specialised sensors. “A USV on its own is just a mothership,” says Neil. “Its purpose depends entirely on the sensors and systems it carries. The intersection of maritime security and the environment encompasses everything from fisheries protection to offshore wind farms to inspection of subsea oil and gas fields.” The vessel’s moon pool (the shaft through its hull through which technologies or divers are deployed into the water) can house a shipping container’s worth of payload, allowing this wide range of tools to be deployed. Onboard, the vessel also integrates ACUA’s own suite of sensors for meteorological and oceanographic data, along with accelerometers to capture wave and motion conditions.

The firm’s aim is not to replace traditional research vessels, but to augment them, expanding the reach of ocean data collection and reducing the need for costly crewed expeditions. This has appeal beyond environmental functions. “Governments’ reduced focus on ESG and sustainability has been a challenge, since many innovation budgets have dried up,” Mike notes. “But moving away from large, high-emission vessels toward smaller, more agile ones has multiple benefits. As well as sustainability, you’re removing people from dull, dangerous, dirty jobs out at sea. And robots don’t mind if they’re stuck bobbing up and down in the North Atlantic on Christmas Day.”

The scourge of untreated wastewater

The scourge of untreated wastewater Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution

Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC

Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC