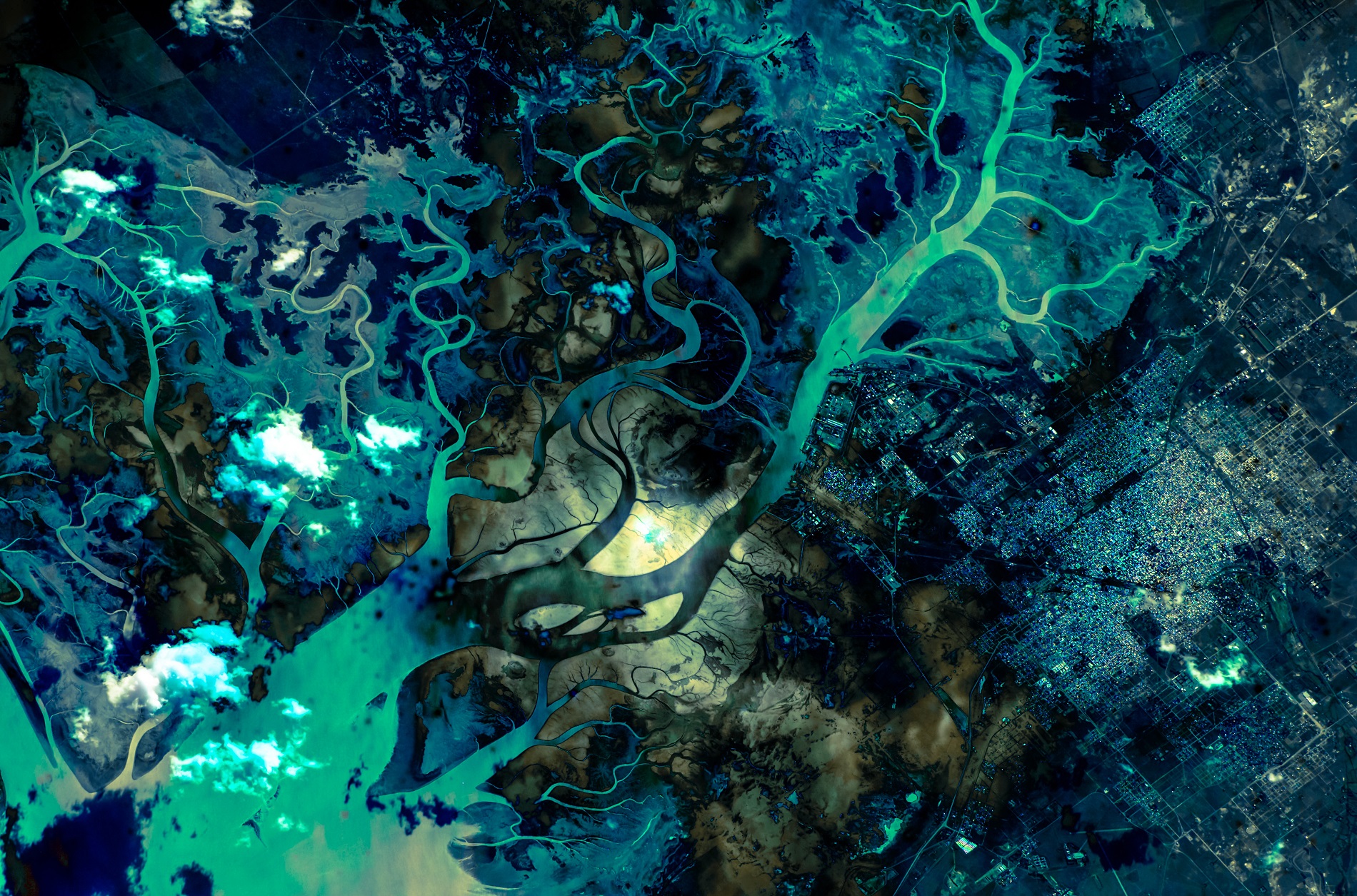

Between 2018 and 2021, I co-led a study on pharmaceuticals in rivers led by Professor Alistair Boxall at the University of York; the project covered 258 rivers worldwide, a third of which had never been studied before. We created sampling kits and sent them to interested participants to help with sampling along pollution gradients from clean upstream water to polluted downstream areas, covering over 1,000 sampling sites. We found that all rivers but two contained pharmaceuticals, meaning pharmaceutical pollution is extremely widespread. Most alarmingly, about 26% of the rivers had concentrations of pharmaceuticals exceeding safety limits. This includes antibiotics that may trigger antibiotic resistance in microbial communities, and chemicals that cause growth retardation or behavioural changes in fish and other aquatic life. For example, high concentrations of chemicals found in antidepressants may increase the chance of fish being eaten by predators. We also found that pollution levels were higher in low- to middle-income countries, those which have access to medicines but lack the infrastructure and policies to properly treat waste and wastewater. This is a global problem, as river water eventually flows into estuaries and then the ocean, where it impacts every country’s marine environment.

In response to our findings, we submitted a proposal to the United Nations in 2020 to continue our work on ocean science and sustainable development. The UN endorsed our Global Estuarine Monitoring (GEM) Program as part of the UN Decade of Ocean Science. We launched the project in 2022 after setting up standard methods and sampling kits; we now have more than 120 scientists involved worldwide, covering over 150 estuaries. We’ve analysed about 60 estuaries so far at our laboratory at City University of Hong Kong, all of which contained pharmaceuticals.

The scourge of untreated wastewater

The scourge of untreated wastewater Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution

Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC

Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC