One of the primary challenges in addressing chronic ocean pollution is the complexity of attributing responsibility or assigning liability. “It’s very difficult to show where water pollution is coming from or pin it on a particular polluter because it’s so diffuse,” says Sandy Luk, CEO of the Marine Conservation Society. “Even if companies are found liable for chemical pollution, the question is whether remediation of the pollution is even possible.”

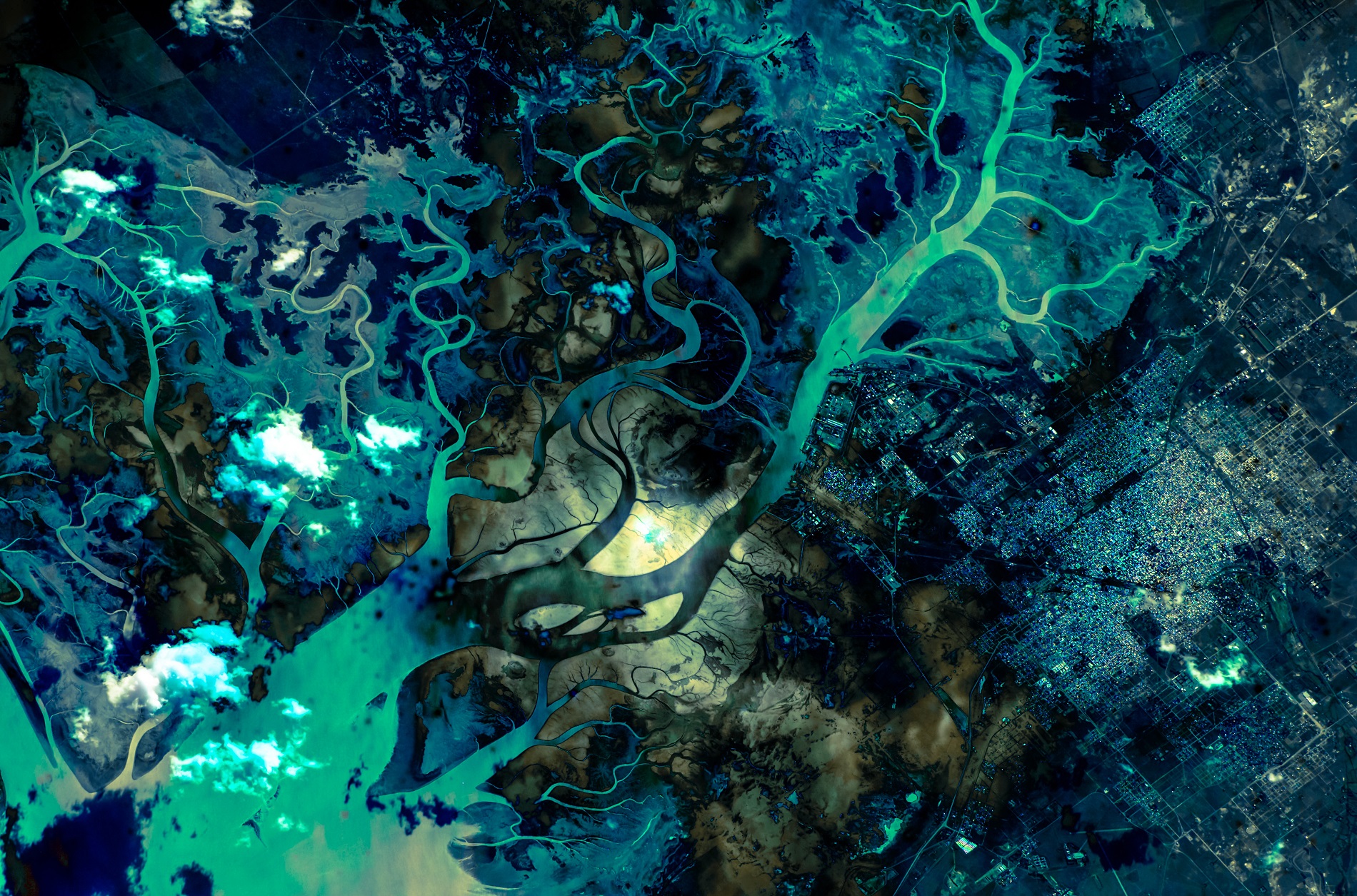

Moreton Bay, near Brisbane, Australia, has experienced chronic pollution since the start of European settlement and agricultural activities, says Professor Bostock, who worked on a study of plastic pollution in the bay alongside Dr Elvis Okoffo at the University of Queensland. Clearing the land for agriculture increased sediment runoff into the bay. The situation further deteriorated as industrial development intensified, leading to the discharge of chemicals from sewerage systems, fertilisers, and wastewater treatment plants into the adjoining rivers, ultimately finding their way into the bay. “Up until the 1980s, people thought the ocean was too large to be influenced by added chemicals until we started seeing toxic algal blooms from the increased concentration of nutrients that were completely changing the chemistry of the bay,” says Professor Bostock.

Algal blooms are fed by nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus, commonly found in agricultural runoff. They cause anoxia by depleting the water of oxygen as the algae die and break down, creating “dead zones” where no marine life can exist. A huge dead zone in the Bay of Bengal is nearing a tipping point where a further reduction of oxygen could strip the water of nitrogen entirely, which scientists warn will have consequences for the global nutrient cycle as well as millions of people’s livelihoods. Toxic algal blooms are triggered by warm water and sunlight, so they will worsen alongside climate change.

The scourge of untreated wastewater

The scourge of untreated wastewater Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution

Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC

Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC