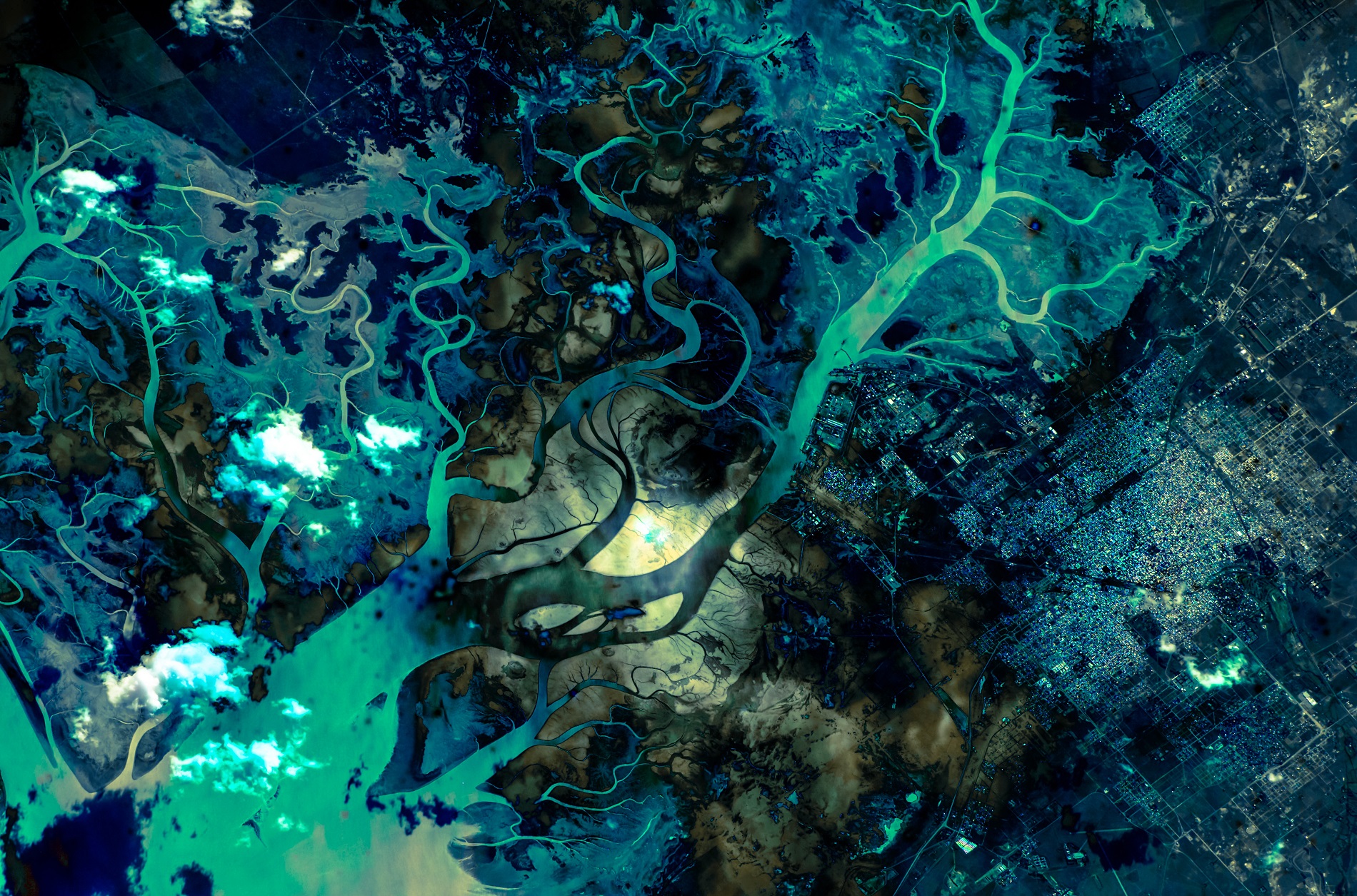

Elsewhere, though, the story is mixed. In the US, for instance, efforts to counter marine chemical pollution stalled as federal efforts ran up against states’ powers to write their own environmental rules, which often favoured business interests. In addition, the so-called lost decade of the 2020s, when successive US administrations were hamstrung through a lack of control of both legislatures, hampered the battle. As a result, the marine environment in the US has continued to deteriorate and is at the worst in its history.

And while South America, which has had some success, still has far to go before its seas are free of chemical pollutants, it is Africa that remains the outlier and the key worry, with its fast-growing and wealthier population boosting demand for goods. That said, money from China’s Belt and Road Initiative and the EU’s €300bn infrastructure fund has financed important infrastructure projects in municipal waste and wastewater management in populous countries like Nigeria, Kenya and Mozambique.

Indeed, the unexpected success of projects in fields like wastewater treatment and municipal waste in the continent’s two largest cities, Lagos and Kinshasa, have shown what is possible even in places with huge populations and near- zero infrastructure. Though their combined population is nearly 70 million, their state-of- the-art facilities mean they now produce less pollution from wastewater and municipal waste than London.

The scourge of untreated wastewater

The scourge of untreated wastewater Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution

Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC

Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC