Chesapeake Bay, on the coast of the north-eastern US, has been the lifeblood for communities for millennia. Indigenous peoples have long relied on the bay for food and their livelihoods, fishing its waters and cultivating crops along its shores. Local tribes like the Pamunkey and Mattaponi carry on their traditions there today. In the time of slavery, maritime labour provided one of the few opportunities for black workers to be treated as equal to whites, with seamen granted legal protections as American citizens. Black oysterers, shipbuilders and sailors, known as “watermen”, played an indispensable role in the Chesapeake economy, fostering a culture that endures among their descendants. Today, over 18 million people live in the bay’s huge watershed, which is also a magnet for visitors.

However, the ecosystems that sustain these communities now face grave threats due to climate change and pollution. Local authorities and organisations like the Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CBF) are leading awareness and restoration initiatives to revitalise the bay and the natural bounty it has provided for generations.

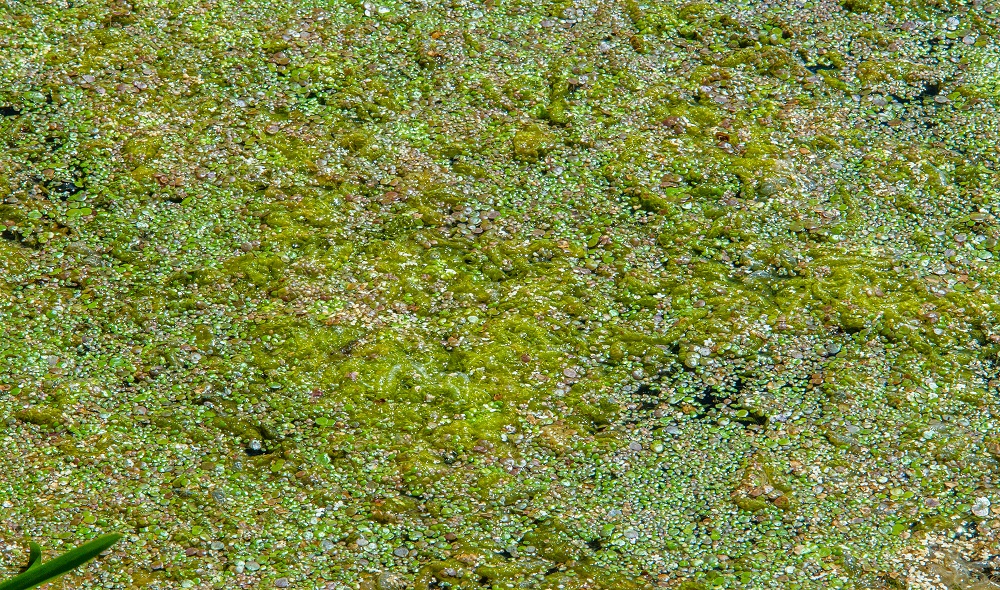

The Chesapeake dead zone

Chesapeake Bay has a massive dead zone—a marine area depleted of oxygen due to nutrient pollution. Excessive levels of nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus from fertilisers fuel the growth of algal blooms, which deplete the water’s oxygen supply. “The simplest way to think about nutrient pollution is that it’s too much of a good thing,” explains Alison Prost, vice president for environmental protection and restoration at the CBF. “All of our natural systems need nutrients, and so do farmers. But too much means the species living in the bay don’t have enough oxygen, and it throws off the whole cycle.”

Pollution has changed life around the bay. Massive numbers of dead fish dent the fishing industry’s returns and recreational fishers’ activities. Swimmers are often advised to stay out of the water following rainstorms, as these wash more toxic nutrients into it. Both fishing and recreational activities are vital for the local economy. “There’s an entire way of life that’s being put at risk,” says Ms Prost.

Pollution has changed life around the bay. Massive numbers of dead fish dent the fishing industry’s returns and recreational fishers’ activities.

Dead zones are difficult to revive. Reoxygenation happens gradually as currents and rivers transport oxygenated water into the bay and the hypoxic water is diluted, allowing species to return. However, if pollution flows consistently into the bay, the cycle will continue and the natural processes that feed oxygen into the water cannot replenish it fast enough. Additionally, warming temperatures accelerate algae growth, compounding the problem. “To restore the bay, we have to prevent pollution from ever entering it, because there’s no way to remove it once it’s in the water,” says Ms Prost.

However, the Chesapeake Bay dead zone has been shrinking thanks to co-ordinated efforts. The six states bordering the bay, federal agencies like the Environmental Protection Agency and local organisations have come together to curb pollution and restore the bay. In 2010, the states [AS1] committed to the Chesapeake Clean Water Blueprint, a plan to restore water quality. By 2022 the bay’s dead zone had shrunk to below its average size, largely thanks to lower pollution from wastewater treatment plants. Nitrogen flows into the bay were cut from 370 million pounds in 1985 to 258 million in 2021, and phosphorus flows reduced from 29 million pounds in 1985 to 15 million in 2021—despite the population increasing by close to 50% over the same period.

“It’s ideal when everyone shares a common goal and combines their efforts and abilities to achieve it rather than taking disparate approaches,” says Ms Prost. The restoration effort has brought together all stakeholders, including farmers, landowners and community members to discuss their roles in the process, she adds. “No single person or entity can solve such a multifaceted problem alone.”

The benefits of oyster restoration

One initiative illustrating the success of the CBF’s approach is oyster restoration. In the 2014 Bay Agreement, state and federal governments, alongside non-profits such as the CBF, agreed on a concentrated effort to restore oyster populations in the ten tributaries feeding into the bay. They pledged to rebuild the reef structures that served as a habitat for oysters and then plant baby oysters on the reef. The structures then became a foundation for other species, including crabs and fish. Thanks to the restoration efforts, the population is growing again. “It’s been a tremendous success; it’s now considered the largest oyster restoration effort in the world,” says Ms Prost.

The impacts of this restoration have been extensive. Oysters are a natural water filter, pumping water through their bodies and ingesting nitrogen and other nutrients into their tissue. One oyster can filter 50 gallons of water a day; the original oyster population of Chesapeake Bay could filter the entire bay in a week. It would take today’s remaining oysters over a year. In addition, oyster reefs protect the coastline by slowing down waves and reducing erosion, which in turn cuts pollution, as less runoff washes into the bay. Creating more protected shorelines also supports the growth of seagrasses and marshes, which store large amounts of carbon, provide habitats for animals and filter the water that flows into the bay. “It’s a wonderful example of co-benefits, where you’re improving water quality, restoring habitats, benefiting fisheries and protecting communities,” says Ms Prost.

Oysters are a natural water filter, pumping water through their bodies and ingesting nitrogen and other nutrients into their tissue. One oyster can filter 50 gallons of water a day; the original oyster population of Chesapeake Bay could filter the entire bay in a week.

Stakeholders have been able to maximise the impacts by concentrating their efforts on only ten of the bay’s affected rivers. Localised efforts can be replicated elsewhere once they are proven to be successful. “This co-ordinated effort is the hallmark of the Chesapeake Bay clean-up,” says Ms Prost. “By targeting the pollution sources, you can focus the solutions in the most impactful places. Our staff work with local stakeholders to focus our resources on the areas that will benefit the most.”

Stopping the flow of pollution

Throughout the process of studying and restoring the bay, the CBF’s experts have identified the main sectors causing the pollution. One is wastewater pollution, which has seen some significant improvements. Treatment plants around the watershed have added enhanced nutrient removal systems to their operations, significantly reducing the discharge of nutrients through wastewater effluent.

The other significant contributors to nutrient pollution are agricultural, industrial and urban runoff, each presenting distinct challenges. The poultry industry in the neighbouring state of Maryland, for instance, discharges millions of pounds of nitrogen-rich ammonia into the bay annually. In 2023 the Maryland Supreme Court rejected a petition by environmental activists seeking stricter regulations on the industry’s ammonia use. The CBF’s litigation team continues to pursue legal avenues to bolster environmental regulations and support restoration efforts, but resistance from industry stakeholders is hampering progress. Addressing agricultural pollution is challenging given the size and scope of the industry in the Chesapeake Bay watershed; states rely on individual farms for 90% of the necessary reductions in nutrient pollution, which makes it difficult to monitor progress and ensure that resources are appropriately allocated. “We know what practices are needed on farms, but the question is how to bring it to scale,” says Ms Prost. The US Department of Agriculture set aside US$22.5m for conservation efforts under the States’ Partnership Initiative in 2022, but more consistent funds are needed to meet pollution reduction targets.

The other significant contributors to nutrient pollution are agricultural, industrial and urban runoff, each presenting distinct challenges.

Tackling urban and suburban runoff pollution poses similar challenges because choices made by individuals, such as selecting lawn care products, play a huge role. “The solutions are more complicated because they’re more individualised,” explains Ms Prost. The CBF aims to engage community members and encourage them to be part of the solution through initiatives like the Clean Water Captains programme, which empowers individuals to serve as ambassadors for the bay in their neighbourhoods. The CBF promotes “green filter” solutions, such as replacing hard surfaces with pervious pavement, converting lawns to native plant gardens and collecting rainwater in barrels. “People are thinking more about these solutions as they notice the increase in intense storms and flooding,” says Ms Prost.

Restoring the bay is an immense challenge that will require sustained, co-ordinated efforts from all stakeholders. Yet what has already been achieved demonstrates what is possible when government agencies, non-profits, industries and community members align efforts towards a common goal. And initiatives such as oyster restoration show that targeted interventions can have widespread benefits. Too much pollution still flows into the bay’s waterways, and states have further to go to reach their commitments to reduce it. Progress will hinge on maintaining local co-operation, partnerships and community engagement.

Back to Blue is an initiative of Economist Impact and The Nippon Foundation

Back to Blue explores evidence-based approaches and solutions to the pressing issues faced by the ocean, to restoring ocean health and promoting sustainability. Sign up to our monthly Back to Blue newsletter to keep updated with the latest news, research and events from Back to Blue and Economist Impact.

The Economist Group is a global organisation and operates a strict privacy policy around the world.

Please see our privacy policy here.

THANK YOU

Thank you for your interest in Back to Blue, please feel free to explore our content.

CONTACT THE BACK TO BLUE TEAM

If you would like to co-design the Back to Blue roadmap or have feedback on content, events, editorial or media-related feedback, please fill out the form below. Thank you.

The Economist Group is a global organisation and operates a strict privacy policy around the world.

Please see our privacy policy here.

The scourge of untreated wastewater

The scourge of untreated wastewater Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution

Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC

Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC