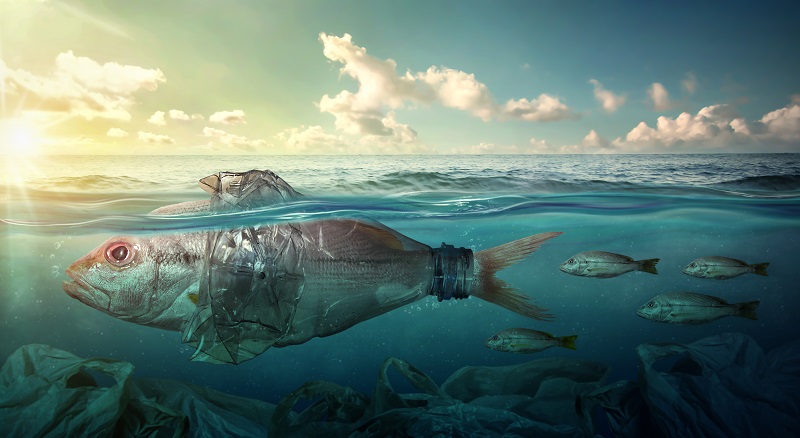

As the International Negotiating Committee (INC) works to create a global plastics treaty, it faces a challenge of unprecedented scale. Plastic pollution has infiltrated every ecosystem from the soil to the ocean. The ocean’s role in human survival cannot be overstated: “1.2 billion people are directly dependent on the ocean for their food, and every breath we take as human beings comes from the ocean,” says Professor Sarah Dunlop, the director of plastics and human health at Minderoo Foundation. This interconnectedness means that plastic pollution in the ocean is a direct threat to human survival.

Plastics consist of a polymer backbone enhanced with a group of chemicals that provide flexibility, durability and stability. However, these chemical additives are not chemically bonded to the polymer structure, which allows them to leach into our food, beverages, air, and, ultimately, the ocean and broader environment. “This is an invisible threat, and we want to make the invisible visible,” says Professor Dunlop.

An umbrella review (a compilation of evidence from existing reviews) by the Minderoo Foundation has exposed the scope of this challenge. By analysing systematic reviews covering 1.5 million people, the study revealed that of the approximately 16,000 chemicals used in plastics, only a fraction has been thoroughly investigated. Thousands remain unstudied, their potential health impacts unknown. However, the existing evidence showed a vast range of impacts, with chemicals found in seminal fluid, follicular fluid, amniotic fluid, umbilical cord blood, children’s urine and breast milk.

“This is an invisible threat, and we want to make the invisible visible”

– Professor Dunlop

These findings resulted from everyday exposure, with normal interactions with plastic piling up to have shocking health outcomes. In men, sperm concentration and DNA were affected; in women, exposure was linked to endometriosis and polycystic ovarian syndrome. “The [effect of] exposure is extensive, across our lifespan and throughout our bodies,” says Professor Dunlop. “This is impacting people’s right to reproduce.” It is also linked to miscarriages, decreased birth weight and asthma in children, as well as higher incidences of metabolic disease, which includes type II diabetes, obesity, cardiovascular disease and some cancers.

These health impacts are inherently tied to ocean health. The dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico, which renders a large area of the ocean uninhabitable, has its origins in Louisiana’s so-called Cancer Alley. This stretch of land polluted by petrochemical and fossil fuel producers, from where plastic comes, has had devastating impacts on the health of local residents. It also feeds into the gulf via the Louisiana River. Activists’ calls for the plastics treaty to include limits on production are aimed at preventing similar disasters.

The ocean has also become a dumping ground for plastic litter, estimated at eight million tonnes annually, which is further leaching chemicals. The Minderoo umbrella review identified persistent chemicals such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), which are added to plastic as flame retardants, in marine mammals. Both these chemicals were marked for elimination under the Stockholm Convention, but they remain in the environment due to decades of accumulation. “Marine mammals bioaccumulate these chemicals as they eat, especially the ones at the higher end of the food chain, which may end up experiencing similar health impacts to humans,” says Professor Dunlop. These accumulated chemicals can additionally be passed on to humans by seafood. While it is unclear whether other problems in the ocean, such as declining plankton populations, can be attributed to plastics, there are clear links to other issues. For instance, one long-term impact of microplastics is disruption to systems like nitrogen cycling and carbon storage, as they are mistaken for food by marine organisms and incorporated into natural processes.

More evidence needed?

There is a lack of research on the health impacts of plastics because we cannot intentionally expose people to harmful chemicals, making it difficult to argue that health outcomes are caused by plastics rather than just associated with them. “It’s illegal to deliberately expose humans to toxic chemicals, yet it happens every day, in a massive uncontrolled experiment,” says Professor Dunlop. “When we see consistent evidence as we demonstrate in the umbrella review, this shows biological plausibility, and we can start talking about plastics as the cause.”

The Minderoo Foundation has chosen an innovative route to determine these effects. “Rather than give people toxic chemicals, we flipped it and decided to reduce their exposure,” explains Professor Dunlop. The PERTH (Plastic Exposure Reduction Transforms Health) trial examines whether reducing plastic exposure could improve cardiovascular and metabolic health. Participants in the trial only consume food that has not been in contact with plastic, including utensils.

“Rather than give people toxic chemicals, we flipped it and decided to reduce their exposure”

– Professor Dunlop

Minderoo is also involved in hybrid epidemiological research, where animal data are used as a basis for what to look for in human epidemiology. A recent publication from The Florey Institute looked at both humans and mice and identifiedy 3-6 x increased risk between maternal (pregnancy) levels of bisphenol A (BPA), a chemical compound used to make rigid plastics, and autism spectrum disorder in boys. According to Professor Dunlop, hybrid epidemiological models are a powerful player in the quest for more causal evidence of harm to human health. “If you have cause, you have attribution, and once you have attribution, you can identify responsibility for the impact those chemicals are having,” says Professor Dunlop.

Work to do at the INC

The INC’s mandate is to develop an internationally legally binding instrument addressing all these severe and interlinked aspects of plastic pollution by the end of 2024. While much of the conversation around the treaty has been on the issue of plastic waste management and end of life, Professor Dunlop believes this is the wrong way to look at the issue.

Rather than managing plastic waste after it’s created, we should prevent its creation in the first place. “We need to do something different and consider the whole life cycle from production onwards; from a health perspective, this means prevention is better than cure,” she says. “The most obvious and simple thing to do is to reduce production.” There has been some progress on including health-focused perspectives, with multiple references to health impacts in the current zero draft. While not explicitly a health treaty, if done right, an effective solution to plastic pollution will also help safeguard public health for current and future generations.

Over the four INC meetings, a division has emerged between the high-ambition coalition of countries, who are calling for a treaty that addresses the full lifecycle of plastic, regulates chemicals, and reduces production, and the fossil-fuel producing states, who do not want to reduce production or regulate chemicals. Some countries remain undecided, the most prominent being the US. However, the US government recently endorsed capping and reducing production and regulating chemicals. “This is a huge shift, and if the US stick to it, other countries will follow,” predicts Professor Dunlop.

Whatever the outcome, the final INC negotiation session will be pivotal in addressing the widespread health impacts of plastic pollution. However, truly mitigating the health dangers of plastic will require continuous, evidence-based efforts, with room for the treaty’s implementation and scope to evolve as necessary. The treaty must serve as a foundation for further action, not an end point. “We need to nail this plastics treaty, and we need to work beyond it, test it to see if it is working and think about the health indicators needed to ensure that it is working,” said Professor Dunlop. “The science-policy interface must drive it. We cannot fail.”

EXPLORE MORE CONTENT ABOUT THE OCEAN

Back to Blue is an initiative of Economist Impact and The Nippon Foundation

Back to Blue explores evidence-based approaches and solutions to the pressing issues faced by the ocean, to restoring ocean health and promoting sustainability. Sign up to our monthly Back to Blue newsletter to keep updated with the latest news, research and events from Back to Blue and Economist Impact.

The Economist Group is a global organisation and operates a strict privacy policy around the world.

Please see our privacy policy here.

THANK YOU

Thank you for your interest in Back to Blue, please feel free to explore our content.

CONTACT THE BACK TO BLUE TEAM

If you would like to co-design the Back to Blue roadmap or have feedback on content, events, editorial or media-related feedback, please fill out the form below. Thank you.

The Economist Group is a global organisation and operates a strict privacy policy around the world.

Please see our privacy policy here.

The scourge of untreated wastewater

The scourge of untreated wastewater Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution

Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC

Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC

Affiliated contentWhy Offshore Wind Needs Looking After

Affiliated contentWhy Offshore Wind Needs Looking After