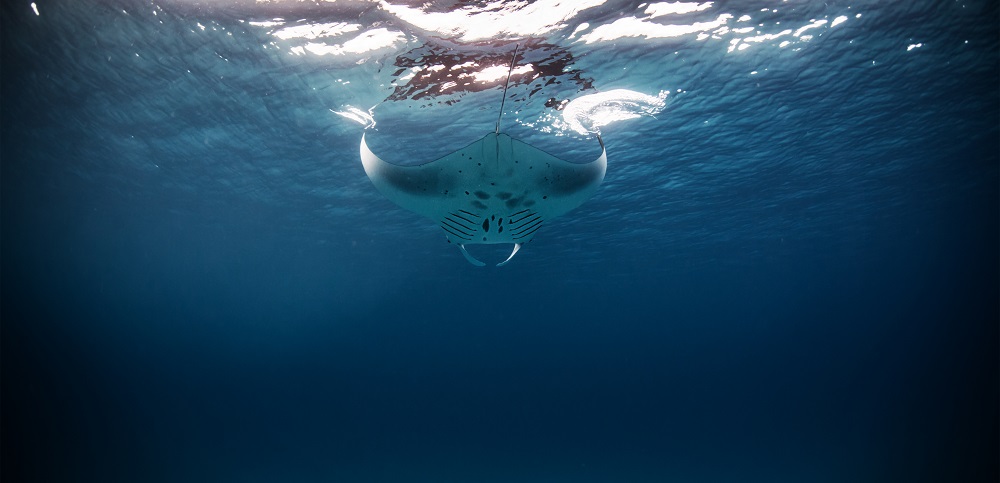

Everyone loves the ocean. People treasure their seaside holidays. Boat-goers get pleasure from watching whales, dolphins and other marine creatures frolic in their natural environments. At home, people marvel at the ocean wonders they see in television documentaries. Policymakers are among those watching, and they listen with alarm to warnings from experts of the grave threats facing ocean life. They view with dismay the visual evidence of ecosystem degradation. And they now have at their disposal a large body of science which documents and explains the causes of the degradation.

Many policymakers are sufficiently moved to push for government action to address the threats to ocean health. For example, a growing number of national and regional government bodies have adopted national ocean policies or formal ocean acidification (OA) action plans. But these and other initiatives too often prove to be isolated undertakings, lacking co-ordination with policy in other realms (such as energy, transport and health) where there are clear overlaps.

And where policies are in place, implementation often founders when priorities change. Eventually, the commitment to act weakens, notwithstanding abundant scientific evidence of a catastrophic decline in ocean health.

When there is so much knowledge about the mounting threats to our ocean, including from ocean warming, acidification and oxygen loss, why do the actions being taken today seem inadequate to reducing them? As the experts we’ve interviewed for this article suggest, much has to do with weaknesses in how that knowledge is communicated to policymakers and other stakeholders. A look at the evolution of ocean literacy efforts helps to understand how the weaknesses can be addressed.

Ocean literacy for citizens and policymakers

Ocean literacy is defined as an understanding of the ocean’s influence on individuals and individuals’ influence on the ocean. As the definition indicates, organisations’ efforts over the past two decades to build such understanding have mainly been targeted at the general public. In recent years, however, the audiences for ocean literacy efforts have expanded to include legislative bodies and forums, businesses, journalists, economists and other groups that help to inform public policy.

“Ten years ago, ocean literacy was mainly seen as a way to bring more ocean science content into schools,” says Francesca Santoro, senior programme officer at the UNESCO Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC), which has been at the forefront of international ocean literacy efforts. “Today, ocean literacy is central in so many discussions, including those related to blue finance and ocean governance.” She notes, for example, that the IOC has published literacy “toolkits” for businesses and for policymakers. She is also proud of the unprecedented prominence given to ocean literacy efforts and goals at the most recent UN Ocean Conference, in June 2025.

The International Alliance to Combat Ocean Acidification (known as the OA Alliance) has from its inception in 2016 sought to build knowledge about the threat of OA and other climate-related ocean changes among government policymakers and administrators. One measure of its success is the 18 OA action plans it has helped local, state and national bodies in North America and Europe bring into existence. It is now also launching a creative communications programme to educate the general public about OA. Jessie Turner, the organisation’s executive director, says the Alliance needs to build awareness of the issue among multiple constituencies. “People still don’t understand what OA is and its linkage to carbon emissions and climate change. The more OA awareness we can build among different groups, the broader support there will be for action to combat it.”

Both of these organisations’ efforts to expand their audiences reflect a recognition that, to galvanise all of society behind restoring ocean health, knowledge-building must extend as widely as possible. However, communicating that knowledge in a way that mobilises action is far from straightforward.

“Ten years ago, ocean literacy was mainly seen as a way to bring more ocean science content into schools”

– Francesca Santoro, senior programme officer at the UNESCO Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC)

Lost in translation

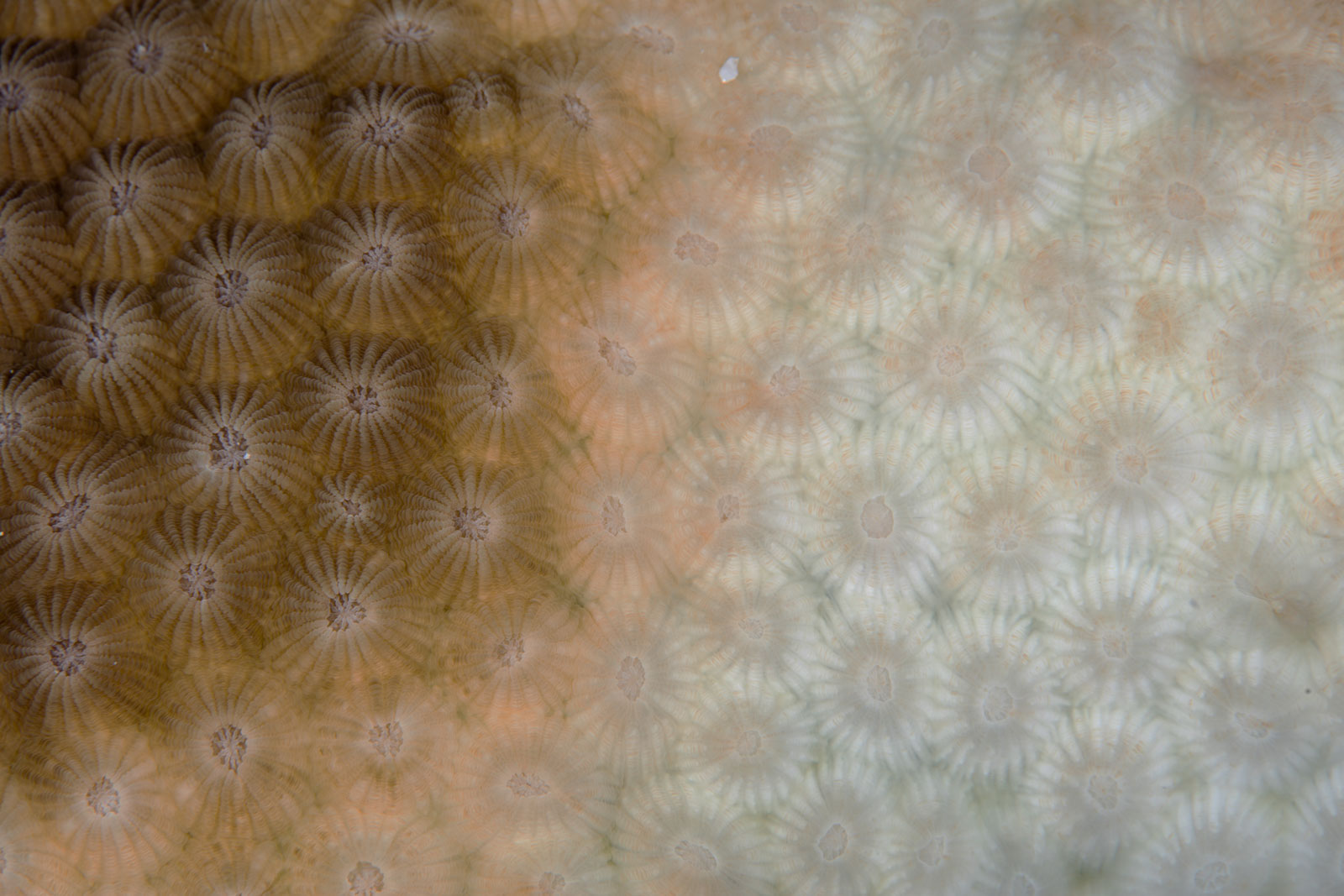

One of the challenges of ocean knowledge-building and advocacy lies in helping non-experts to visualise the threats to it, through illustrative as well as written content. Two of the biggest threats, OA and deoxygenation, affect marine organisms by changing seawater in ways the naked eye cannot see. “It is a struggle to make what is invisible visible,” says Ms Santoro.

That challenge is complicated by the determinant role of carbon emissions in creating those threats. (CO2 acts directly to increase seawater acidity, while it intensifies deoxygenation through atmospheric and ocean warming, of which emissions is the primary cause.) “The increase in CO2 entering the ocean and the changes in chemistry it’s producing are extremely difficult to visualise,” says Ms Turner, “but we need such visual tools to complement the other ways we’re calling for climate and ocean action.” The OA Alliance has sought to do that with a digital animation it released in June 2025. (Back to Blue has produced similar content.)

Scientists understand these processes without difficulty, but the same cannot be said of all non-scientists, including public officials. It is critical that the latter develop an understanding, as they are the key decision-makers and budget holders for the largest scale initiatives society can take to combat threats to marine life. Scientists themselves have had limited success in doing so. “It’s not just about communicating what, for example, OA is and why it matters,” says Ms Turner. “Scientists are good at that. It’s about communicating how governments can take up the challenge of fighting it with greatest impact.”

Ms Santoro is hopeful that today’s young scientists will eventually be able to do that. “Young scientists we interact with today understand it is vitally important that their science is communicated widely,” she says. The IOC operates a training programme for early career ocean professionals. In it, says Ms Santoro, “the types of skills they want most to learn relate to policy advocacy and science communication.”

Ms Turner believes “bridge actors” are also needed to reach policymakers. These will be experts who have a sufficient understanding of ocean science and the capability to see where it fits in a policy landscape. She believes such individuals, who are rare to find today, could eventually emerge from multilateral institutions like intergovernmental policy groups or regional development banks, where multidisciplinary expertise is the norm rather than an exception.

Such “bridge actors” should be well-positioned, says Ms Turner, to make ocean health messaging more relevant to what public officials care most about—the wellbeing of their constituents. “It’s not enough that we convince policymakers that there are grave threats to ocean health,” she says. “We need to take it further and convince them that those are simultaneously threats to people’s health—their livelihoods, incomes and even physical wellbeing.”

Holistic knowledge for holistic policy

More effectively connecting OA, deoxygenation and other ocean stressors to jobs, economies and public health will serve a higher purpose: helping governments understand the need for a co-ordinated, whole of government approach to combatting those stressors and improving ocean health.

It is difficult to find such an approach being pursued at national level anywhere today. “Fragmentation is one of the biggest weaknesses of ocean governance,” says Ms Santoro.

It doesn’t help, she adds, that ocean science itself can be compartmentalised. “Academia doesn’t naturally encourage collaboration between people with different fields of expertise. Academic institutions need to address that. Transdisciplinarity is the only way to truly understand and deal with these issues.”

“Fragmentation is one of the biggest weaknesses of ocean governance”

– Francesca Santoro, senior programme officer at the UNESCO Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC)

That also rings true for ocean governance. The causes and impacts of ocean stressors tend to cut across different economic sectors—fisheries, agriculture, shipping, energy and tourism, for example—and the ministries, agencies and departments responsible for their management. When it comes to OA, for example, several of these bodies may be pursuing actions that impact it, but they do not necessarily connect with each other to co-ordinate the most effective response or larger messaging, says Ms Turner. “They all have their own mandates, and these take priority. Their actions may strengthen the impact of those being pursued by other agencies, but they may also conflict with or even weaken them.”

“They all have their own mandates, and these take priority. Their actions may strengthen the impact of those being pursued by other agencies, but they may also conflict with or even weaken them”

– Jessie Turner

Overcoming this fragmentation requires commitment from across government to pursue overarching ocean policy outcomes. Once those outcomes are recognised, says Ms Turner, it will be easier for each agency or department to see how its actions to combat OA or other climate-related stressors serve those broader policy outcomes. This is also a challenge for ocean science, she says: “We really need scientists to recognise that their work must be directly relevant to desired policy outcomes.”

Fragmented policy encumbers international as well as national efforts to restore ocean health. In our next article in this series, we discuss mindset changes that can help ocean stakeholders at all levels to pursue the restoration of ocean health in a more holistic and systematic way.

EXPLORE MORE CONTENT ABOUT THE OCEAN

Back to Blue is an initiative of Economist Impact and The Nippon Foundation

Back to Blue explores evidence-based approaches and solutions to the pressing issues faced by the ocean, to restoring ocean health and promoting sustainability. Sign up to our monthly Back to Blue newsletter to keep updated with the latest news, research and events from Back to Blue and Economist Impact.

The Economist Group is a global organisation and operates a strict privacy policy around the world.

Please see our privacy policy here.

THANK YOU

Thank you for your interest in Back to Blue, please feel free to explore our content.

CONTACT THE BACK TO BLUE TEAM

If you would like to co-design the Back to Blue roadmap or have feedback on content, events, editorial or media-related feedback, please fill out the form below. Thank you.

The Economist Group is a global organisation and operates a strict privacy policy around the world.

Please see our privacy policy here.

The scourge of untreated wastewater

The scourge of untreated wastewater Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution

Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC

Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC