Marine biodiversity loss is an undisputed fact. For example, as cited in our 2024 report on ocean acidification and biodiversity loss, global catches of coral reef fish have been declining since the start of this century. A primary cause is a continuing degradation of the world’s coral reef cover that supports such species, due mainly to ocean warming. But there are other contributors. In coral reef and other ocean environments, higher acidity levels from excess CO2 build-up—ocean acidification (OA)—weaken marine organisms; overfishing depletes fish populations; algal blooms resulting from nutrient run-off produce harmful toxins, reduce oxygen levels, and block sunlight; and discarded plastic causes direct harm to organisms.

It is recognised that biodiversity loss imposes economic costs on society. Direct costs of reduced marine biodiversity include lost fisheries income from depleted fish stocks, which has a knock-on effect in the form of job losses and higher seafood prices. OA, if not stemmed, will exacerbate this by limiting the growth, and possibly threatening the survival, of keystone shellfish species in affected waters. Costs also come in the form of lost tourism receipts, as the reduced diversity of marine species limits the attraction of popular recreational activities. And costs will be incurred from increased public spending needed to reinforce natural coastal protection weakened by the loss of mangroves and coral reefs.

Marine biodiversity loss also has indirect costs in its negative impact on other ecosystem services, such as nutrient cycling, water purification and oxygen production in nearshore waters. Critically, it also reduces the ocean’s ability to absorb CO2 from the atmosphere, a major contributor to climate change. (That excess CO2 leads to the heightened acidity that in turn acts to weaken calcifying organisms.) Biodiversity loss also detracts from medical research, as fewer marine species means reduced potential for discovery of new biomedical materials.

In this Q&A article, Back to Blue will discuss the causes and impacts of marine biodiversity loss with two experts: David Obura, chair of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) and founding director of CORDIO East Africa; and François Mosnier, head of ocean programme at Planet Tracker.

What are some of the most alarming manifestations of biodiversity loss among marine species that you are seeing, whether caused by OA or other stressors?

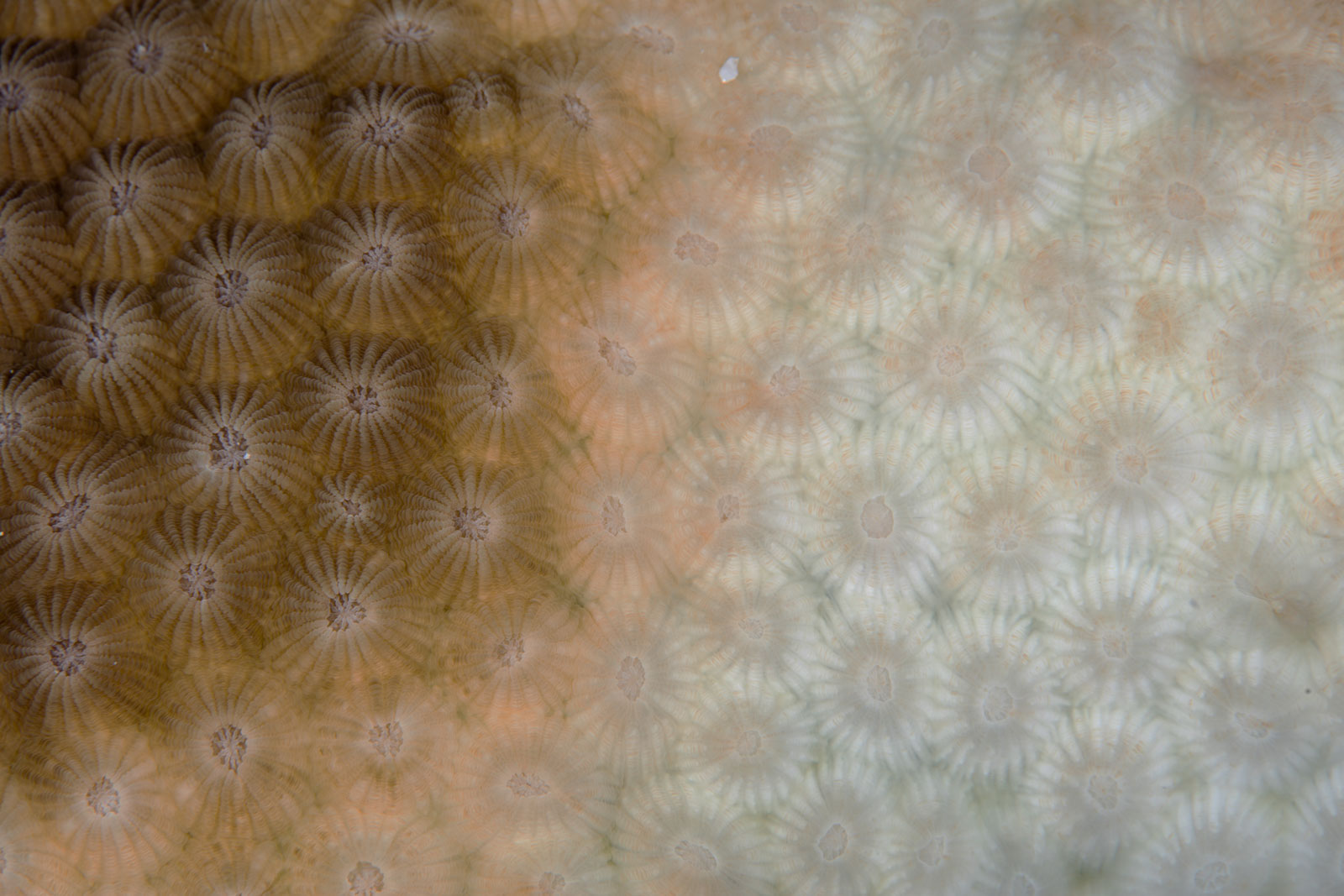

DO: There are many. One that comes immediately to mind is the decline of yellowfin tuna stocks in the Indian Ocean. And there are reports of severely depleted fish stocks in West African waters as a result of overfishing by European fleets. The decline of live coral is a particularly visible example. Coral reefs have been suffering from a multitude of pressures, of which OA is just one. Major multi-year bleaching events caused by climate warming is a prime cause; one such event has been under way for the past two years with no sign of abating. But on top of that are pollution and changes in water chemistry (including changes wrought by OA) that weaken organisms, and then there’s overfishing. We’re not relieving these pressures on the ocean in any meaningful way. Overall, the global economic system is not taking its foot off the accelerator, and coral reefs are suffering a thousand cuts every day.

How does a decline in one species affect the wider ecosystem of which it is part?

FM: Let’s take the example of Indonesian tuna. Planet Tracker has projected a decline of at least 25% in tuna catches by the country’s fishing fleets between now and 2050 under different climate change scenarios. (Overfishing has been the main source of pressure on Indonesia’s tuna stocks, but the effects of climate change on its waters is also a significant causal factor. Ocean warming and nutrient cycle disruption are the main stressors, while OA is an indirect contributor.) Tuna is a top predator and a big mover of nutrients, which fertilise the ecosystem’s waters and feed phytoplankton, which themselves are essential for oxygen production and carbon uptake. So a decline of tuna creates a massive imbalance in the ecosystem’s food chain.

[BACK TO BLUE: OA impacts the food chain in other ways, having a ripple effect from the chain’s lowest levels, where it weakens forms of plankton that feed so many higher forms of marine life. And by weakening and stunting the growth of pteropods, it reduces a key source of nutrition for organisms such as salmon, squid, herring and krill (itself a major food source for several species of whale).

What would be the economic impact of such a decline in tuna stocks?

FM: It would be significant: a decline in fishing industry revenue of up to 30% from today’s levels and a near total collapse of the industry’s profits. That’s a big disruption to a major creator of value for the Indonesian economy. Depending on how the government reacts, that would also likely lead to some loss of employment in the industry.

Can such losses be averted?

FM: Yes, but it requires investment today. Fishing businesses need to invest in the future of the biomass population so that it’s made more resilient. It requires, for example, reducing fishing of those stocks that are overexploited and adopting more selective fishing methods. Government needs to do its part by, for example, imposing curbs on fishing where industry is slow to do so voluntarily. It’s also critical that government enforces seafood traceability standards to improve the transparency of companies’ fishing practices.

Why is it important to quantify biodiversity loss in terms of its economic impact?

DO: If we lose a species, we lose the benefits that the species and its ecosystem directly or indirectly generates for us. Its more than the loss of a source of food, income or employment. Marine ecosystems provide other services, such as shoreline protection, climate regulation and carbon sequestration. We lose those services as marine species decline and their interactions decline in terms of their vibrancy, resilience and capacities. A direct cost can be calculated for that. We can identify, for example, how coastal protection benefits a town and its port and what it would cost if that protection were lost—for example, the cost of building a breakwater or other defences.

Quantifying the financial costs of biodiversity loss helps to focus government and business minds on the severity of the challenge in terms they can easily understand. But we also need to be able to quantify the intangible, non-monetary benefits that communities get from coastal ecosystems. Island cultures, for example, derive a lot of value from their coastlines in terms of recreation, happiness and their sense of place. We need to develop metrics that capture the multiple values of these intangible benefits.

Do businesses that use ocean resources implement sustainable practices when they understand the cost of inaction?

FM: Too often, companies fail to make the link between environmental sustainability and financial health. Yet there are examples of companies which have acted, often for business reason. They include a seafood business in Southeast Asia seeking to ensure sustainability of its fish supply, and a global food company investing in the restoration of marine habitats where it sources seafood. All of this makes sense: analysis of 300 companies across the seafood supply chain shows a positive correlation between a company’s reliance on sustainable fish stocks and its profitability, whilst profit margins tend to decrease with greater reliance on overfished stocks. It’s not a perfect correlation, and there are too many companies which fail to report data on profitability or fishing practices. But it definitely suggests a link between sustainable behaviour and profitability.

DO: I can’t say I’ve seen businesses respond in that way yet in the regions I’m most familiar with, such as East Africa. But it’s certainly understandable that businesses should. Whether we’re talking about companies or countries, potential responses to threats of biodiversity loss will hinge to a large extent on wealth. When you have a high or at least secure level of income, you can forego some short-term profit to build longer term resilience. Without secure income, you may not have any ability to do that.

We need to do a lot better at communicating to businesses the value of investing in the long-term resilience of ocean resources. We at IPBES will seek to do that with our next https://www.ipbes.net/business-impact, which will be published in February 2026. Among other things, it identifies around 40 ocean-specific actions that businesses can take to strengthen the resilience of marine biodiversity.

Is there any hope of reversing the decline of species that are under threat from overfishing, pollution, OA, and other stressors?

FM: There are certainly success stories. One encouraging example is the recovery of Atlantic bluefin tuna. Twenty years ago, the species was in danger of collapse after decades of overfishing. But in 2006 regional fisheries organisations agreed a set of management measures to try and stem the decline. Crucially, observers were deployed to make sure the rules were respected, and the population has grown around fivefold since then. That’s a fantastic achievement. The IUCN [International Union for Conservation of Nature] now includes the species in its “least concerned” category.

We’re also seeing wins at smaller scales. In Kenya, for instance, some coastal communities have revived the practice of tengefu, which is “set aside” in Swahili. It basically means closing off a part of the sea to fishing so that fish populations can replenish themselves there. The results are frankly incredible. Fish biomass in an area where the practice has been implemented are now about four to five times greater than in adjacent areas.

[BACK TO BLUE: The 16,000 marine protected areas (MPAs) in existence worldwide and other efforts to restore coastal habitats have led to the recovery of mangroves, seagrasses and salt marshes that help ecosystems adapt and build resilience to OA and other stressors.]

DO: It depends on the life histories and the biology of those species. Things like sea grasses and mangroves are very amenable to replanting and restoration, and there are successful examples of their recovery. It’s very difficult, however, with species like corals, because of their biology and because the conditions they’re growing in are getting progressively worse. There are some promising techniques being developed that could yield successes in the future, but they’re unlikely to be applied at a scale that can replace the coral reefs we’ve already lost.

Is it too late, then, for corals and other similarly endangered marine species?

DO: It’s not too late, but the longer we put off the hard work, the more costly it becomes. Climate change is a long run problem, and if the world had made the right choices 30 years ago, we’d not be in this state now. When will decision-makers start to behave like ‘good ancestors’ for future generations?

We can conserve the coral reefs if we stop pushing responsibility to those who will come later. Conservation and restoration of ocean habitats is critically important to future security, and to bring some endangered species back from the brink. But we have to recognise that we’re in a new world. We’re no longer in what scientists call the Holocene, the geological period of relative climate stability and biotic abundance that we’ve enjoyed for several thousand years. We’re moving into the Anthropocene, which is bringing a very uncomfortable climate, and over-extended biological systems, due to all the damage that we humans have been doing to the environment. We have to adapt and pull back from the brink. That means, among other things, re-thinking how we measure prosperity and growth. The longer we wait to do so, the worse it will get.

Editor’s Note:

To explore the complex and under-acknowledged relationship between ocean acidification and biodiversity loss—including its economic and ecological consequences—read Back to Blue’s full 2024 report: Ocean Acidification and Biodiversity Loss

EXPLORE MORE CONTENT ABOUT THE OCEAN

Back to Blue is an initiative of Economist Impact and The Nippon Foundation

Back to Blue explores evidence-based approaches and solutions to the pressing issues faced by the ocean, to restoring ocean health and promoting sustainability. Sign up to our monthly Back to Blue newsletter to keep updated with the latest news, research and events from Back to Blue and Economist Impact.

The Economist Group is a global organisation and operates a strict privacy policy around the world.

Please see our privacy policy here.

THANK YOU

Thank you for your interest in Back to Blue, please feel free to explore our content.

CONTACT THE BACK TO BLUE TEAM

If you would like to co-design the Back to Blue roadmap or have feedback on content, events, editorial or media-related feedback, please fill out the form below. Thank you.

The Economist Group is a global organisation and operates a strict privacy policy around the world.

Please see our privacy policy here.

The scourge of untreated wastewater

The scourge of untreated wastewater Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution

Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC

Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC