“California is often a leader in advancing environmental policies, but for plastics, until very recently, that wasn’t the case,” says Dr Jackson. “We were doing piecemeal things that didn’t address the pace and the scale of the problem in our state, or at a global level where the size of our economy gives us influence.”

In late 2020 therefore, Dr Jackson and her colleagues decided to change tack and try to short circuit the legislative. They proposed a so-called ballot initiative, which under Californian law would be put to a referendum if it attracted sufficient support, to reduce plastic use by 25% and add a levy on each piece of plastic sold, which would fund alleviation.

As the measure gained traction, something unexpected happened. Fearing the passage of a law they had no influence over, businesses such as food producers, which had shown little interest in legislation, suddenly came forward to engage with the environmental groups behind the ballot initiative. Over long months of discussions, environmentalists negotiated directly with companies including General Mills and Procter and Gamble, eventually agreeing a set of measures that were signed into law without the need for a referendum.

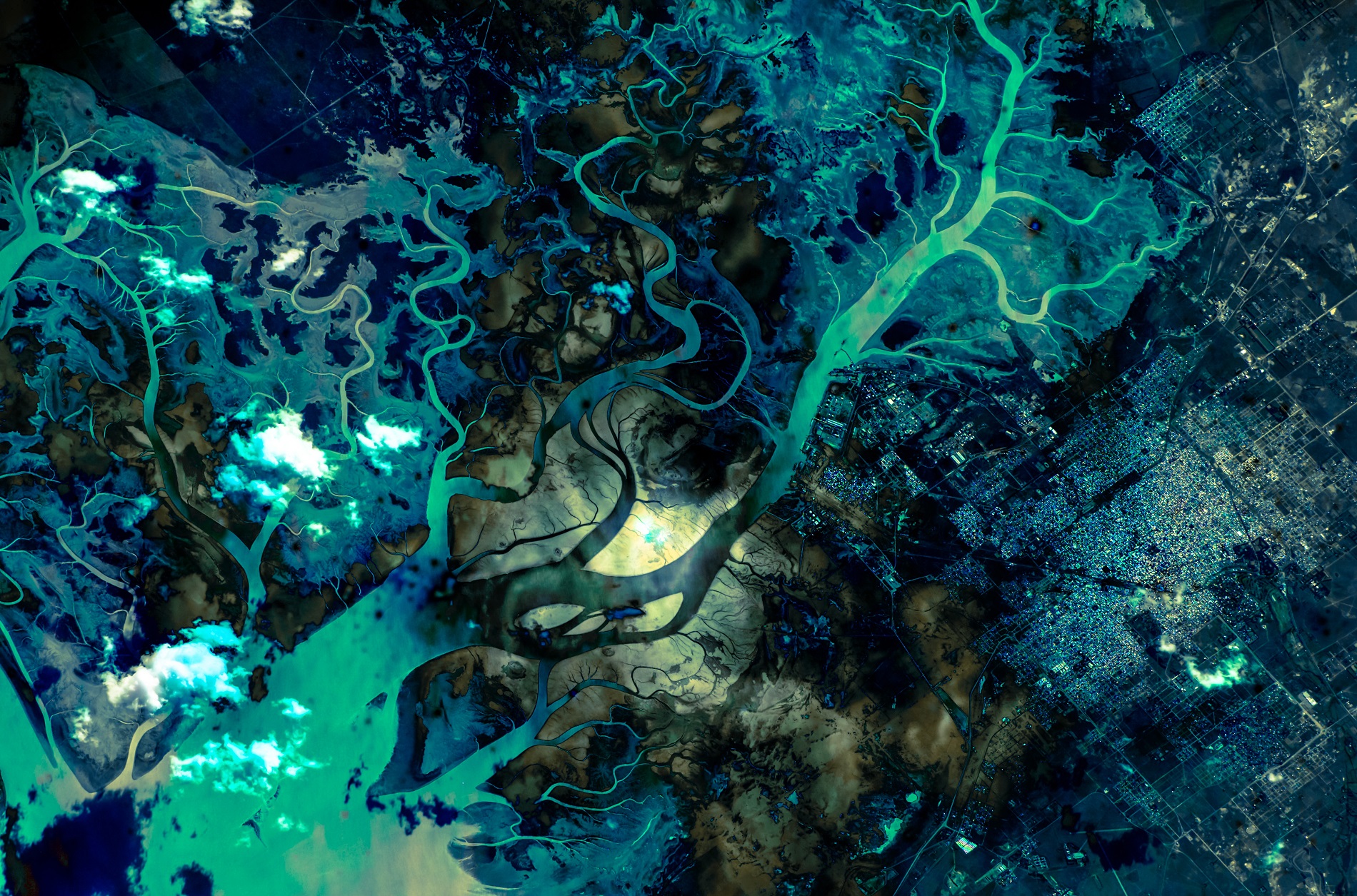

The scourge of untreated wastewater

The scourge of untreated wastewater Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution

Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC

Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC