The ocean is the lifeblood of our planet, providing food, livelihood and oxygen for millions of people. Yet, untreated sewage is poisoning our seas, threatening marine ecosystems and directly impacting coastal economies. Every year, vast quantities of domestic wastewater—filled with bacteria, excess nutrients and harmful chemicals—flow untreated into rivers, lakes and the ocean. This pollution severely disrupts marine ecosystems, leading to dead zones, declining fish stocks and biodiversity loss, all of which threaten coastal communities and industries that depend on healthy oceans.

The harmful impacts of this wastewater extend beyond the ocean, degrading farmland and spreading diseases like diarrhoea, straining health systems and food supplies.

To better understand the costs of inaction towards untreated domestic wastewater, this study assesses how wastewater disrupts fisheries, agriculture and health—three areas where the economic and social costs are particularly severe.

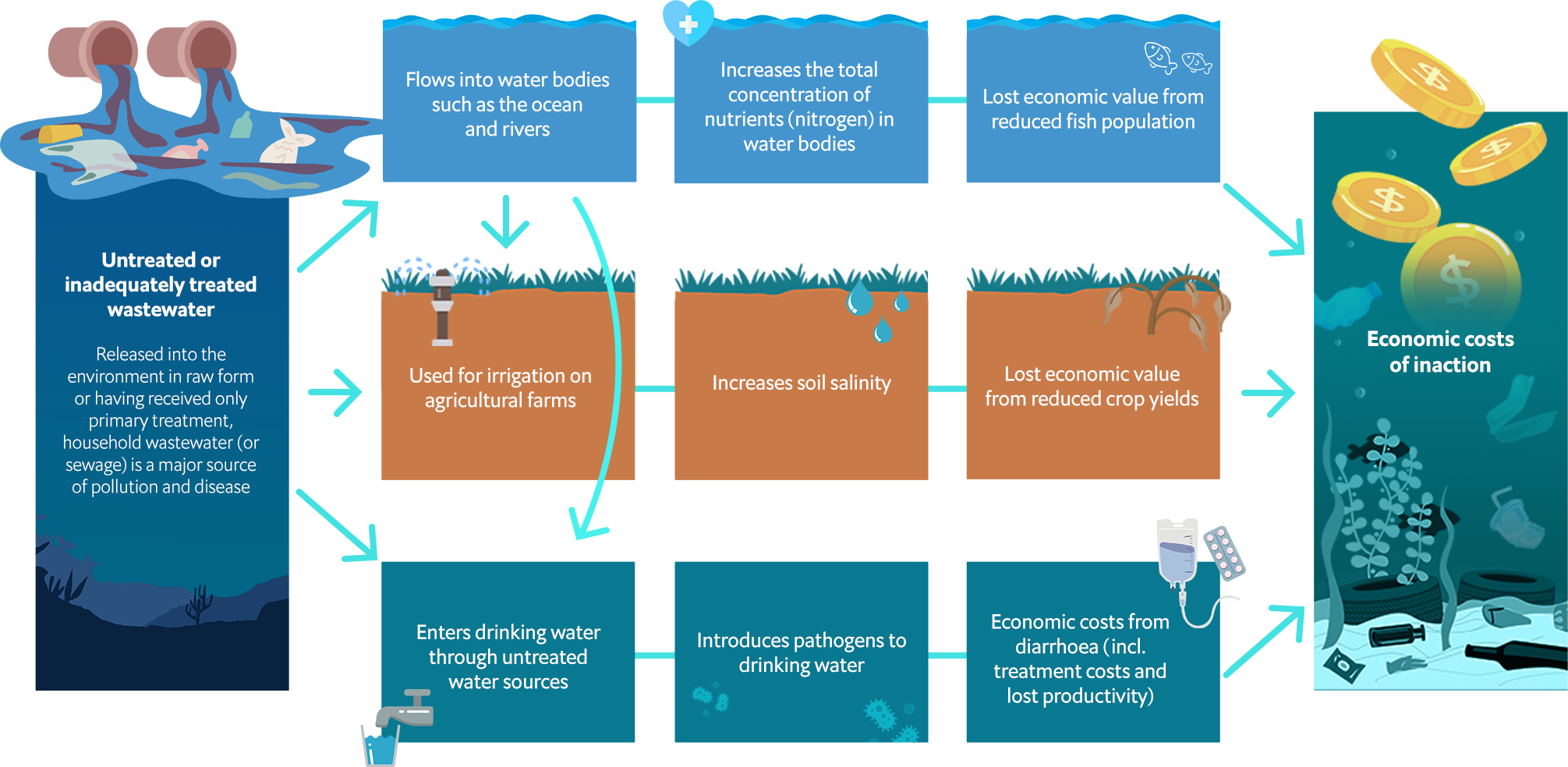

The ripple effects: how sewage pollution harms economies and ecosystems

This is a pilot attempt to measure the economic costs of inaction towards treating domestic wastewater in five countries: Brazil, India, Kenya, the Philippines and the UK.

Our analysis in this initial undertaking finds that the economic losses linked to untreated wastewater are sizeable, particularly for the four lower- and middle-income countries in the model.

The true impact of wastewater pollution extends beyond our estimates. Our analysis of fisheries losses only considers reduced fish populations, not damage to marine ecosystems or tourism. Health covers only diarrhoea caused by the E.coli pathogen—the most widespread wastewater-related disease—while other illnesses remain uncounted. In agriculture, we assess just three major crops per country and focus only on salinity, leaving out other contaminants. A full study would reveal even greater economic and environmental costs.

FISHERIES: OCEAN DEAD ZONES

Untreated wastewater flowing into the ocean raises nitrogen levels, fueling algal blooms that deplete oxygen and create dead zones, leading to reduced fish populations. This disruption weakens marine ecosystems, reduces fish stocks and threatens the livelihoods of coastal communities dependent on fisheries. Our analysis quantifies the lost value to fisheries from reduced fish populations as a result of the harmful effects of domestic wastewater.

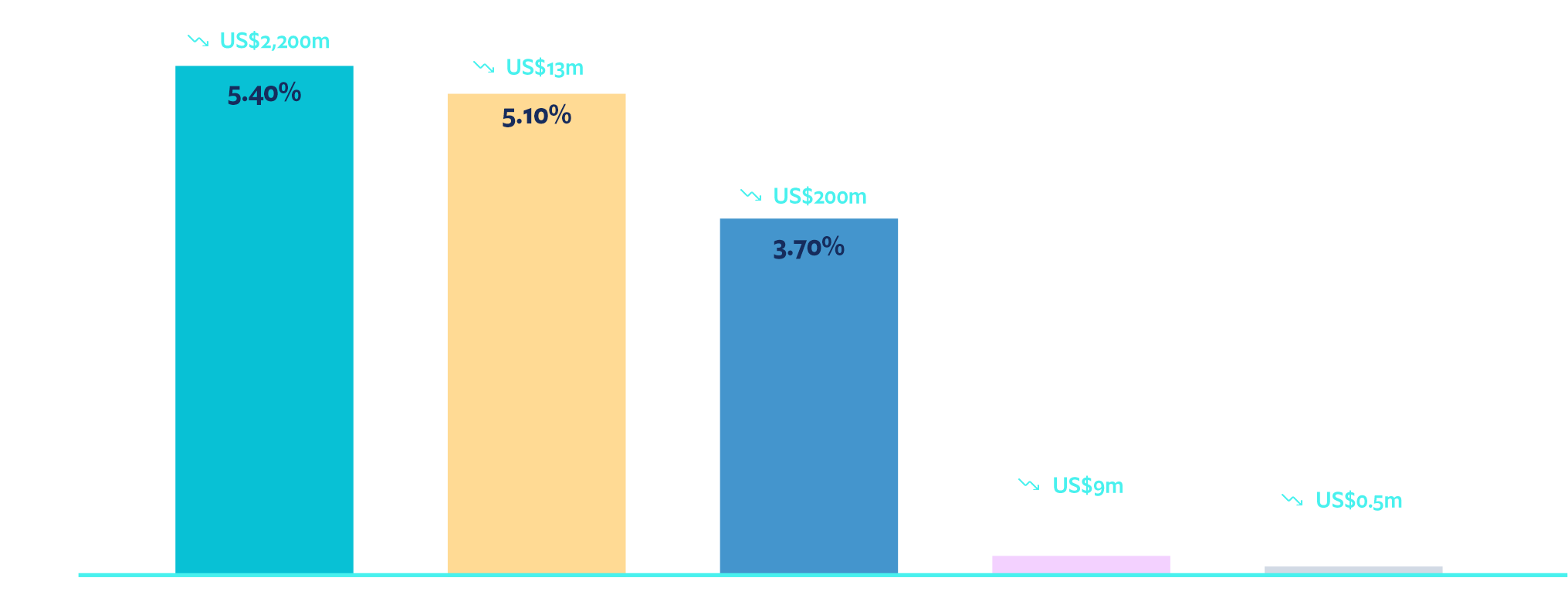

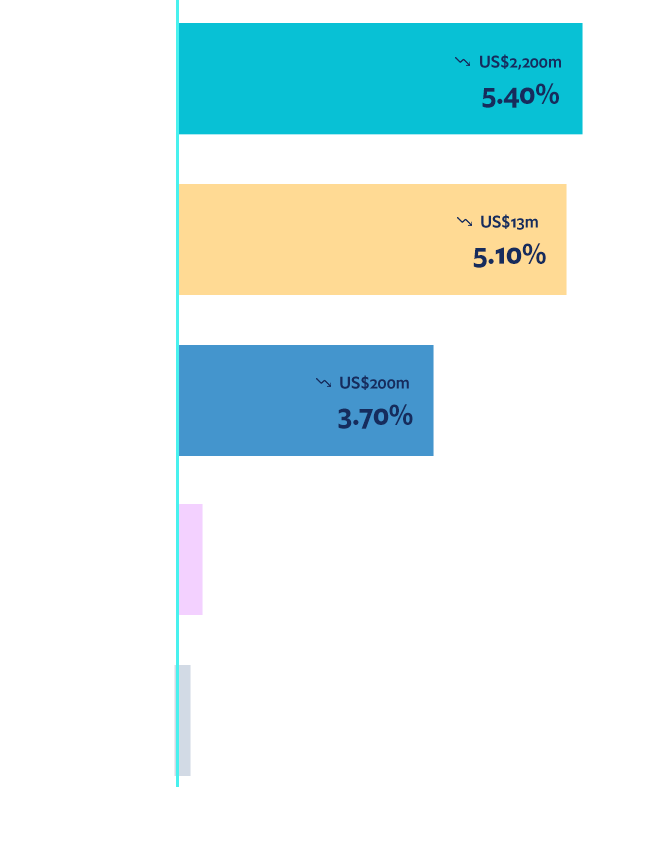

India and Kenya, with wastewater treatment rates as low as 21% and 11%, suffer the greatest fisheries losses—5.4% and 5.1% of the value of fisheries is lost respectively. Brazil faces US$200m in losses due to its large-scale fishing industry.

Economic loss in the fisheries sector (as a % of the current economic value of fisheries)

"Declining water quality driven by sewage or other terrestrial runoff brings changes not just in fisheries but also in corals, which is a sensitive habitat. And in areas where you have these kinds of important species, wastewater and other types of pollution can have cascading effects on employment and coastal stability."

- Will Le Quesne, director of the Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science

Coral reefs, vital for biodiversity and tourism, are also severely impacted by declining water quality. While these impacts are not included in this model, the stakes are exceptionally high—particularly for nations like Maldives and Palau, where reef tourism drives over 40% of GDP.

AGRICULTURE: LOST YIELDS ON FARMS

In developing countries, 10% of agricultural land is irrigated with raw or partially treated wastewater, exposing crops to toxic heavy metals like zinc and chromium, as well as harmful levels of nitrogen and phosphorus. Prolonged use of untreated wastewater leads to soil salinisation, drastically reducing crop productivity.

Countries with more water-intensive agricultural systems face the greatest impacts, as rising salinity and contamination lower productivity and threaten food security.

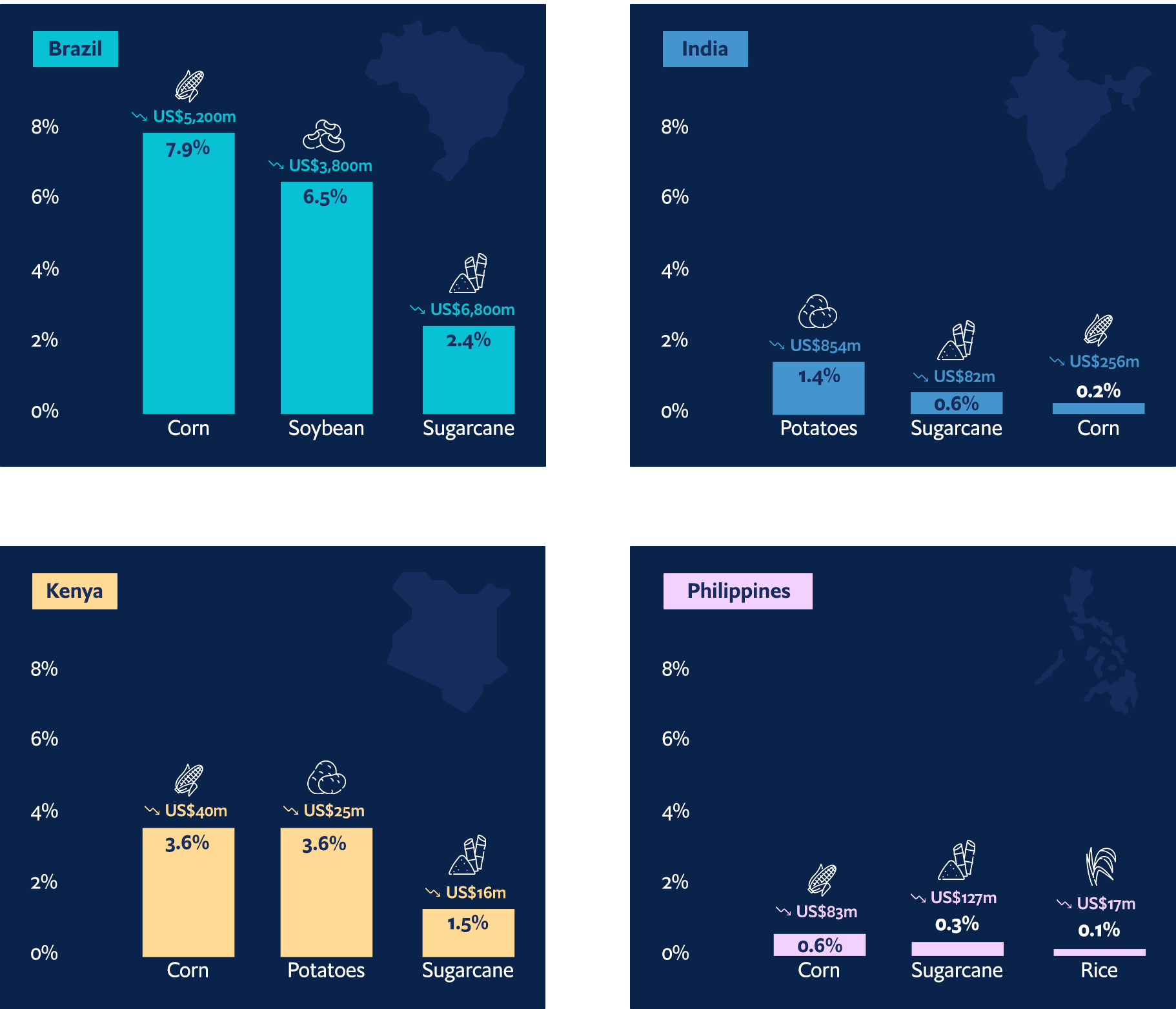

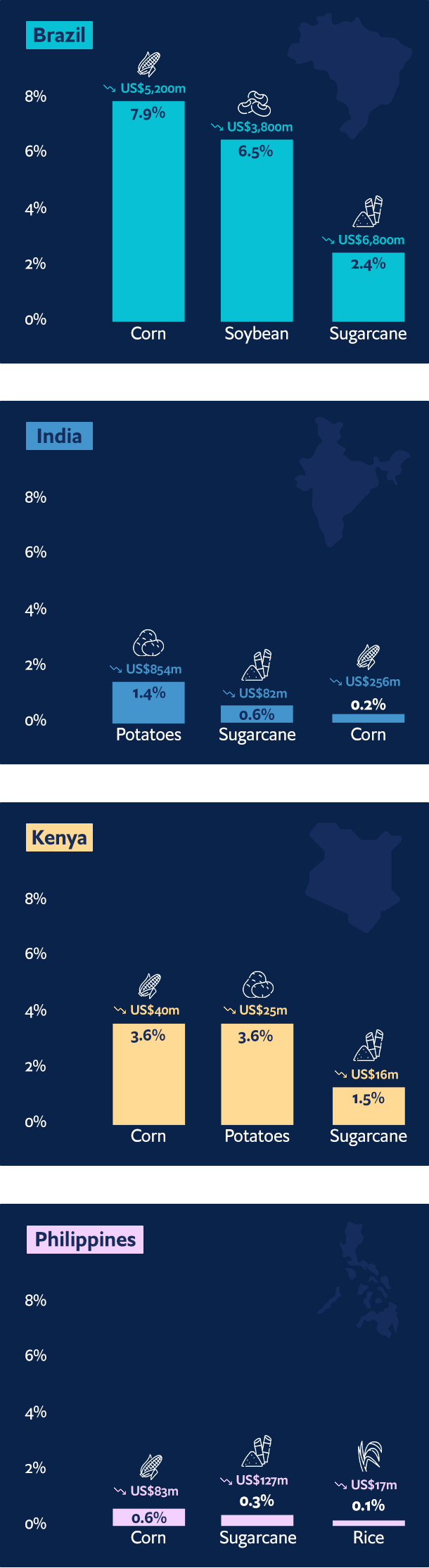

This model quantifies the economic impact by estimating crop losses due to soil contamination from wastewater irrigation, focusing on the three largest crops in each country.

Brazil’s agriculture sector loses US$15.7bn annually due to untreated wastewater. India follows with a US$1.2bn loss, driven by high production and the sensitivity of crops to soil contamination. Rising salinity levels, coupled with untreated wastewater use, jeopardise food production in these countries.

Crop value loss as a result of soil contamination from irrigation using untreated wastewater (as a % of the current value of crop production)

Human health: lost productivity and rising healthcare costs

Untreated wastewater spreads diseases like diarrhoea, cholera and typhoid, stunting children’s growth, reducing educational outcomes, and placing long-term burdens on healthcare systems and economies.

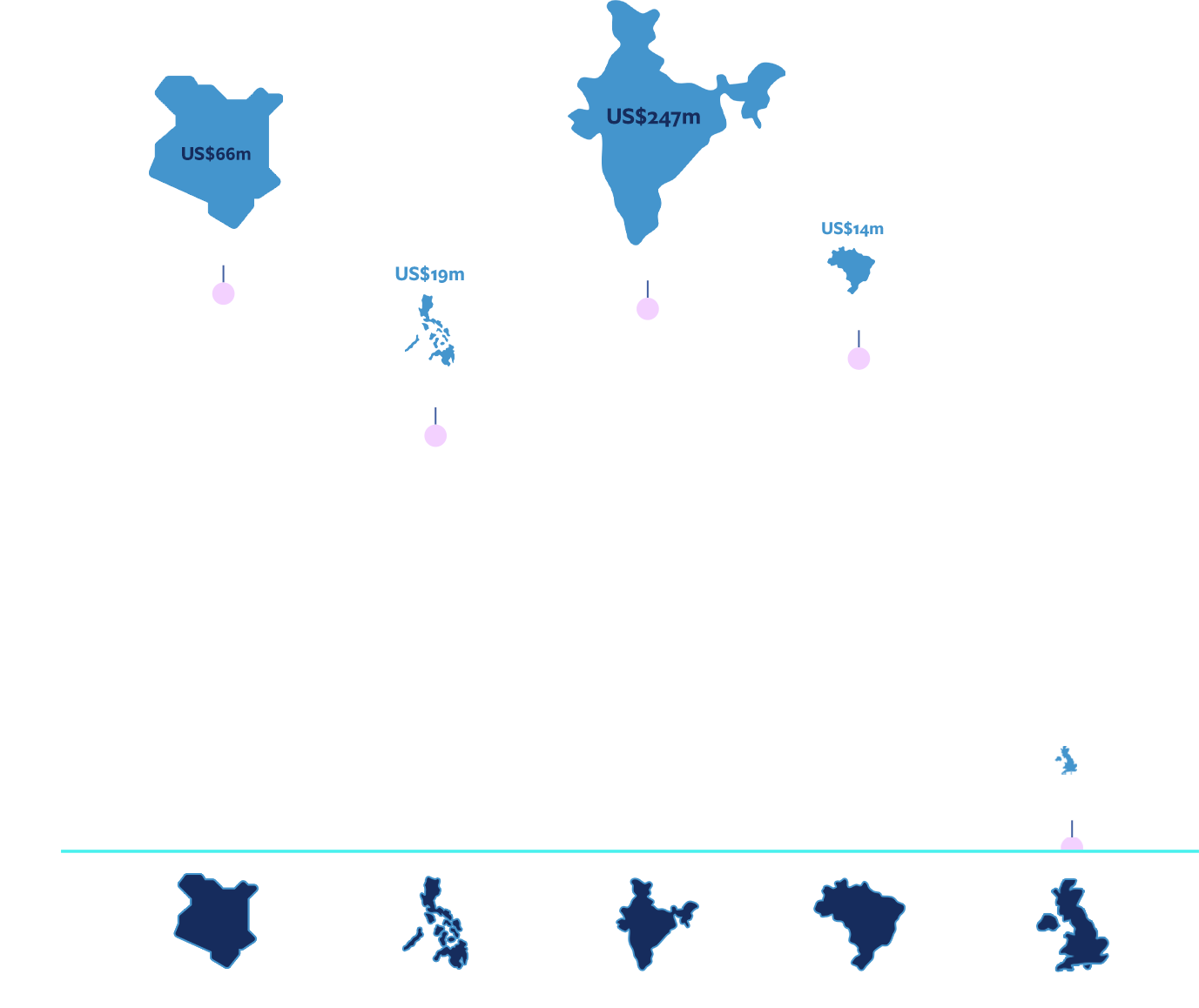

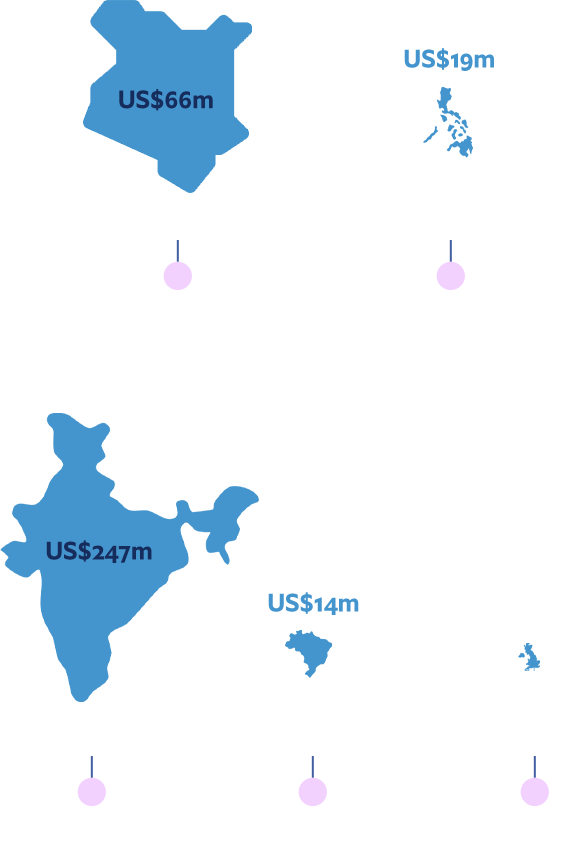

This model focuses on the health and productivity impacts associated with the most common waterborne illness: diarrhoea caused by the pathogen E.coli. Immediate costs include hospitalisation and lost wages due to sickness. Future costs arise from school absenteeism, leading to diminished productivity and less prosperous communities.

The total economic costs (including both healthcare treatment costs and productivity loss) associated with diarrhoea caused by the E.coli pathogen range from 6.3% (US$14m) in Brazil to 6.9% (US$246.7m) in India, with negligible losses in the UK due to its high levels of wastewater treatment.

Additional economic costs associated with diarrhoea caused by untreated wastewater

Key takeaways:

Invest early and proactively in infrastructure to prevent greater losses: delaying action multiplies economic costs in the form of treatment costs, environmental damage and lost productivity. Investing upfront in sewage infrastructure and wastewater treatment can be a cost-effective way to prevent economic losses.

Decentralised solutions can fill the gap of wastewater inequality: in areas lacking large-scale infrastructure, decentralised wastewater treatment systems and water reuse initiatives offer practical alternatives. These approaches can improve sanitation, protect water sources and generate economic benefits such as energy recovery.

Wastewater can be a valuable resource for sustainable development: countries must recognise that it can be repurposed into organic fertilizers, used to produce biogas, or transformed into a renewable energy source. With the right policies that go beyond investment and focus on circularity, wastewater can shift from an environmental challenge to a driver of economic, environmental, and societal benefits.

Back to Blue is an initiative of Economist Impact and The Nippon Foundation

Back to Blue explores evidence-based approaches and solutions to the pressing issues faced by the ocean, to restoring ocean health and promoting sustainability. Sign up to our monthly Back to Blue newsletter to keep updated with the latest news, research and events from Back to Blue and Economist Impact.

The Economist Group is a global organisation and operates a strict privacy policy around the world.

Please see our privacy policy here.

THANK YOU

Thank you for your interest in Back to Blue, please feel free to explore our content.

CONTACT THE BACK TO BLUE TEAM

If you would like to co-design the Back to Blue roadmap or have feedback on content, events, editorial or media-related feedback, please fill out the form below. Thank you.

The Economist Group is a global organisation and operates a strict privacy policy around the world.

Please see our privacy policy here.

The scourge of untreated wastewater

The scourge of untreated wastewater Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution

Slowing

the chemical tide: safeguarding human and ocean health amid

chemical pollution Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC

Hazardous chemicals in plastics - the discussions at INC

Young people and ocean literacy">

Young people and ocean literacy">